February 2017

No one saw it coming. Not even after the extraordinary primary season. Not even after tumultuous conventions in Cleveland and Philadelphia. Not even after populist risings in Europe that reflected a transatlantic mood of discontent. Not even after Brexit roiled markets worldwide. Not even after pollsters repeatedly found widespread dislike of both major party candidates. Not even after the debate debacles.

No one foresaw the mass transfer of Bernie Sanders loyalists to the Libertarian ticket on Election Day 2016.

Now “Feel the Bern” has become “Warm to the Weld.”

The number-crunchers have repeatedly confirmed that a stunning majority of those who voted for Sanders in the Democratic primaries either voted for the Gary Johnson-William Weld Libertarian ticket or boycotted the election. Coupled with a smaller but still significant fraction of tea partiers shifting Libertarian when Ted Cruz endorsed Johnson, the sudden swing to the latter, undetected in October, temporarily plunged the nation into paralyzing shock.

No one could have foreseen that Johnson’s upset of both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump in several large states would put the outcome in the hands of Congress for the first time since 1876.

And that’s when it became clear that Americans needed to know their Constitution better.

Results on election night befuddled the pundits, to say nothing of the candidates themselves. Clinton claimed victory based on her solid popular-vote total, but then backtracked. The landslide repudiation of Trump left the billionaire uncharacteristically mute. And Johnson could only repeat his utter uncomprehending delight in all the attention.

That ancient device, the Electoral College, proved even more crucial than in the George W. Bush-Al Gore contest of 2000, when the election turned on Florida ballots and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Bush had won the state. Democrat Clinton won a thin popular majority overall, but narrow losses in several key states left her short of the Electoral College majority required for victory. Republican Trump managed to win several states where many Democrats bolted to the Libertarians or Greens; similarly, Johnson picked up states when Republican voters followed their many leaders who could stomach neither The Donald nor Hillary.

The certified electoral vote tally (270 needed to win): Clinton-Kaine 259, Johnson-Weld 201, Trump-Pence 78.

Most shockingly, the third-party candidate had finished second.

Now what?

Twice before in U.S. history, the House of Representatives had to decide. That’s so because of the process laid down in Article II as altered by Amendment XII: from the persons having the highest numbers not exceeding three on the list of those voted for as President, the House of Representatives shall choose immediately, by ballot, the President.

But it gets even weirder. The Constitution prescribes not that the House votes individually, but that the votes shall be taken by states, the representation from each state having one vote. (That’s the way the Electoral College votes.) The U.S. representatives held multiple ballots throughout December. Some states swung to Clinton, a few to Johnson, fewer still to Trump. And some deadlocked. Again Clinton led, but never reached a majority of the 50 states. Repeated votes only hardened the impasse.

January 3 came, and with it the new Congress that had been chosen back in November. Republicans had lost seats in both Senate and House, but still held hairbreadth majorities in both. Yet the new House members proved no more able to forge a majority result, despite the inevitable ugly horse-trading behind the scenes.

January 20 — Inauguration Day — loomed. The pundits and pols went back to their pocket Constitutions. The nation turned its attention to the Senate, because from the two highest numbers on the list, the Senate shall choose the Vice-President. Each U.S. senator could cast an individual vote, but could choose only between Kaine and Weld, the top two electoral vote-getters.

As president of the Senate, outgoing Vice President Biden oversaw the drama of choosing his successor. Kaine, Virginia’s junior senator, as one of the candidates gallantly excused himself. The tally: 51-48. Joe Biden’s potentially decisive tie-breaking vote was unneeded. William Weld was the vice president-elect.

Back to the Constitution. If no president is chosen by January 20, according to Amendment XX, then the Vice President elect shall act as President. And that’s what happened. In very modest and hasty ceremonies, William Weld took the vice-presidential oath of office. With no precedent to go on, Chief Justice John Roberts stepped to the microphone and announced that the newly sworn VP was now the Acting President.

Now what? The House has remained paralyzed, though evidently retains constitutional power to try to stitch together a majority of state delegations to elect a president. But on Inauguration Day Donald Trump, pronouncing the process a “huge disaster,” suddenly and shockingly removed his name from consideration.

House Speaker Paul Ryan (the president-in-waiting if something happens to the 71-year-old Weld) had become the nation’s power broker. Ryan so far has refused to schedule more votes on the remaining two candidates. Meanwhile the Acting President has called for patience and unity, and promises to start naming a Cabinet.

As of today, February 17, 2017, Ryan remains mum, but his actions indicate the Acting President may well soon be formally declared the 45th president of the United States.

What seems to be emerging is a behind-the-scenes deal to create some kind of coalition government, European parliamentary style, that will include moderate leaders from both parties.

In the meantime, wild rumors are flying. Tim Kaine reportedly will be offered the vice-presidency — in accordance with Amendment XXV: Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.

Several Obama Cabinet members have agreed to stay on, most notably Secretary of Defense Ash Carter. Mike Pence may be asked to accept the post of his deputy. Other notables from both parties evidently will be named to fill Cabinet vacancies. And President Weld, it is reliably said, will renominate Merrick Garland to fill the Supreme Court vacancy.

Indeed, these extraordinary crossing-the-aisle maneuvers could signal that a new party may be forming along centrist lines. If they fail, the worst constitutional crisis in the nation’s history, at least since the Civil War, will continue to play out before a polarized and horrified electorate.

But if they succeed, Americans may well “warm to the Weld,” and We the People will be truly “welded” back together.

One can only fantasize such an outcome.

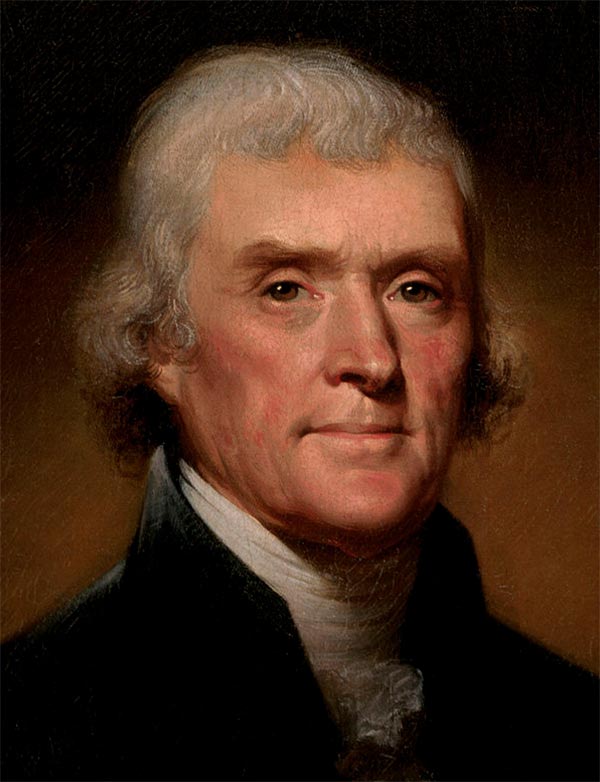

Thomas Jefferson

Earlier odd elections

Such a scenario, if it happened, would become the most bizarre presidential election in American history. But there have been some nearly as weird.

In 1800, U.S. representatives, following the Constitution’s unamended Article II, broke an inadvertent tie, choosing Thomas Jefferson over Aaron Burr. In 1824, when four candidates split the electoral vote, the House picked John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson. And in 1876 an ad hoc joint commission — including senators, representatives, and justices from both parties — was created to adjudicate 20 disputed electoral vote returns from three states. It awarded them all, and the presidency, to Rutherford Hayes. An echo of 1876 occurred in 2000, but this time it was the Supreme Court that decided Florida’s electoral votes belonged to George Bush as already certified, overriding a messy contest over recounts and securing Bush’s victory.

Whoever actually moves into the White House next January 20 will be chosen by a somewhat convoluted process intentionally designed to preserve a role for states, avoid a direct national popular plebiscite, and hold open the possibility that an individual elector could renege on an iron pledge to a specified candidate (it’s happened!). Strong third (and fourth!) party tickets — and they’re surprisingly frequent — can further roil the waters. Just ask Woodrow Wilson, who won in 1912 because Theodore Roosevelt siphoned votes from his fellow Republican, incumbent William Taft, throwing the election to the Democrat Wilson.

The positions and politics of presidential candidates get the most attention, but on this Constitution Day 2016, we ought to pay attention to the Constitutional underpinnings as well.

Someone’s implausible fantasy might, thanks to our durable but intricate charter, at some point become history’s next weird election.