This year marks the 100th anniversary of a watershed event: America’s entry into Europe’s “Great War” — World War I. But what led a once-neutral U.S. to intervene overseas? What spurred a vision to join a “war to end all wars,” a war to “make the world safe for democracy?” As we commemorate this episode, it is crucial to recognize that America’s involvement came not just from German provocation, but out of a social context — an impulse, dominant in American life and politics for two decades.

That impulse was called “Progressivism.”

The aptly named Progressive Era (roughly 1900–20) was a time of bold energy and bright confidence. Americans of all political persuasions — and their political leaders — strove to engineer progress (hence the label) through both private and governmental activism, at home and eventually abroad.

The war thus served as one of many applications of the widely shared Progressive effort to shape a better civilization. The war offered a perfect laboratory for the United States, under the moral vision of the Progressive Presbyterian professor president, Woodrow Wilson, to lead the whole world toward the same progress Americans expected in their homeland. As it turned out, the ugly realities of war and a failed peace sabotaged the progressive dream.

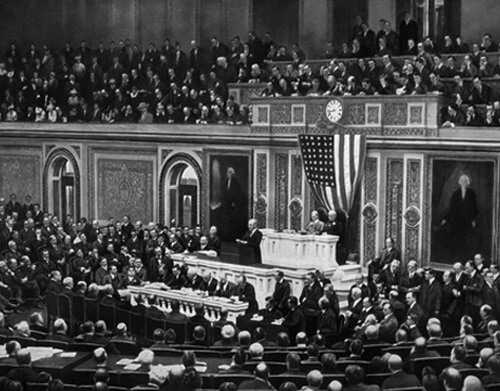

Woodrow Wilson delivers his war message.

However, the era (including wartime and its aftermath) did have lasting consequences. Among the most important yet least noticed was a characteristically Progressive reinterpretation of the Federal Constitution — whose 230th birthday we observe on September 17. Both in peace and in war, both in understanding and application, both through judicial rulings and outright amendments, the American Constitutional order was transformed in the early 20th century; we live with that legacy into the 21st.

The Progressives

Today’s self-styled “progressives” are kin but not identical to the bipartisan array of political activists of the Progressive Era. Back then Progressives could be found in both parties. They confidently applied traditional morality to what they saw as corrupting social influences. And they were a wildly varied lot, disagreeing not just on policies, but also on principles (such as military intervention vs. pacifism).

Nevertheless, they shared three core ideas:

- A managerial impulse: They had great faith that trained experts, especially in government at all levels, could so orchestrate change as to bring about real social progress.

- A democratic impulse: They believed that the people could and should share in the process and functioning of governing so that it served the public good rather than special interests, or as writer Benjamin DeWitt put it in 1915: that political institutions could be made “more difficult for the few, and easier for the many, to control.”

- A humanitarian impulse: They championed an unabashed moralism in the cause of social progress, initiating not just charitable but also positive government programs to “relieve social and economic distress.”

In short, Progressives of a century ago worked first to reform government, then to mobilize government to reform America. More specifically, they sought to (1) engineer progress by (2) curbing the villains — exploitative corporations and corrupt politicians — while (3) aiding the victims of corporate and political abuse.

The Progressive impulse transformed the role and reach of the federal government. The driving motivation was to use expanded federal authority to counterbalance the power of giant new industrial corporations and to address an array of social problems stemming from the industrial revolution. In so doing, Progressives, starting with three bold presidents, had to rework traditional Constitutional practice — through both Supreme Court reinterpretation and formal amendment.

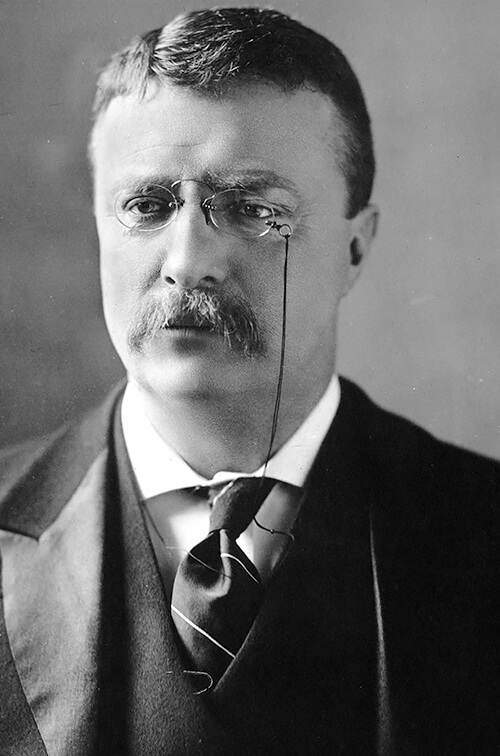

President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–09)

The Progressive presidency

President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–09) began this sea change by reinterpreting the presidency as the single nationally elected steward of the national welfare. His successors, William Taft (1909–13) and Woodrow Wilson (1913–21) intentionally enlarged the vision and powers of the office even further, but in different ways consistent with their different temperaments.

Fittingly, in the election of 1912 all three faced off against each other. Indeed, four candidates won substantial vote totals that year — two Republicans, one Democrat, and one Socialist. All were Progressives of one sort or another. Former President Theodore Roosevelt (27 percent) and incumbent William Taft (23 percent) split the Republican vote, allowing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to slip in with 42 percent of the popular votes (but an Electoral College majority), even though a radical Eugene Debs polled 6 percent.

No conservative voice could be heard. Campaign rhetoric trumpeted the righteousness of Progressive causes. Voters reveled in the new presidential activism.

The Progressive Court

The Progressive presidents found allies on the Supreme Court, which endorsed new regulatory roles for the federal government in areas of morals and welfare once exclusively belonging to states. The Court’s rationale rested, oddly, on a broadened reading of the Constitution’s clause dealing with interstate commerce, which “is vested in Congress absolutely,” held Justice John Marshall Harlan in a 1903 case (Champion v Ames). Most anything related to the economy or society crosses state lines, so counts as “interstate commerce,” and thus comes under federal purview. Then in a case related to sex trafficking a decade later, Justice Joseph McKenna proclaimed that “the powers reserved to the states and those conferred on the nation ... are to be exercised ... to promote the general welfare, material and moral.” This was dramatically new doctrine, inserting the national government into all sorts of matters, like prostitution.

Most famously, in Muller v Oregon (1908), the Court ruled a state could protect women by limiting their workday (to 10 hours!). They accepted the arguments of a brilliant lawyer and future Justice, Louis Brandeis, that (1) social and medical science showed overwork harmed women’s health; (2) a state could justly legislate to protect women; and therefore (3) established legal logic and precedent could be superseded.

Undergirding this technical line of reasoning was a new legal theory, known opaquely as “sociological jurisprudence.” Said famed Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., “the life of the law ... has been experience.” New York Law School Professor William LaPiana explains this approach thus: “Society creates law and law has to respond to society.” In short, a Progressive-minded Court now shaped its constitutional rulings based on social conditions rather than mere theory or precedent.

The result was a vast expansion of federal power. And it wasn’t just the principle of active national government that was promoted. Progressives embraced an innovative mechanism to reshape society: the federal commission or executive agency, an entity within the executive branch to which legislative and even quasi-judicial powers are assigned. The Court gradually accepted expanded authority for the older Interstate Commerce Commission, paving the way for many more such agencies — from the Federal Trade Commission set up in the Wilson administration to the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, created in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

The Progressive amendments

There are two different paths to constitutional change. One, as we have seen, is judicial reinterpretation. The other is to amend the Constitution itself. Few eras in American Constitutional development have seen such rapid alterations to the national charter as the Progressive era, during which four articles were added:

The Progressive amendments are curious. They reflected different, and differently enduring, aspects of the early 20th century Progressive vision. They were adopted in pairs — two in the middle of the era, two at the end. They illustrate both new tools for expanded federal power (16th and 17th) and new social concerns brought under federal mandate (18th and 19th).

The first two were essentially procedural, but with far-reaching consequences. They had relatively short histories, arising from recent demands to place democratic constraints on wealth and power. The third and fourth were embraced for their radical changes to improve society, but would not be supported by the same groups today, and had relatively subdued impact; indeed, one was repealed. And these two later amendments culminated longstanding crusades, indeed had already been embraced at state and local levels before receiving nationwide sanction.

The rest of this essay will be devoted to the first pair. Next September 17, I will take up the second pair. Each story illustrates the Progressivism of a century ago — an impulse ancestor to, yet different from, what drives today’s self-labeled progressives.

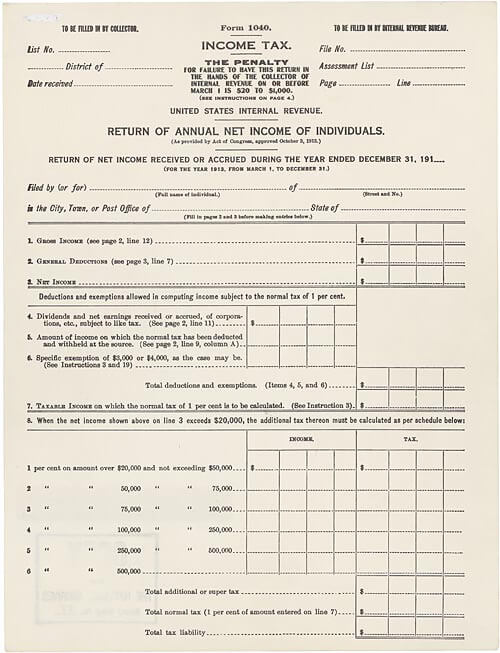

The first income tax form, from the National Archives.

16th Amendment (1913): Tax on incomes

Expanding federal power required expanding federal tax revenue, especially when Progressives were seeking to curb the power of great wealth and enlarge the scope of government-provided services. The first procedural change to the Constitution, therefore, was to authorize Congress to levy taxes on incomes.

The first article of the Federal Constitution (See 9, Clause 4) says that “direct taxes” must be allocated according to state populations, like representatives in the House. During the Civil War, both Union and Confederate Congresses passed taxes on incomes to help pay war costs. Though the measure was repealed after the war, the Supreme Court, in a narrowly framed case, let the concept stand.

Why an income tax? Or better: Why not an income tax? In America’s early history, most personal wealth was held either in real estate or personal property (including slaves). But it was not practical to tax land from Washington, D.C., especially if federal taxes had to be laid proportionately on the states. So for most of American history, well into the 20th century, Congress worked around the difficulty by relying on tariffs — that is, taxes on imported goods — as the main source of national revenue. In fact, the tariff came to be not only an instrument of government fund-raising but also a controversial technique of economic development, raised high enough to protect domestic manufactures against foreign imports.

By contrast to American protectionism, Britain, as early as the mid-1800s, had converted to free trade, and with it an income tax. Other Western European nations had followed suit.

Why then, after following a different path, did the U.S. switch to accepting an income tax in the Progressive Era? In the new industrial economy of the later 1800s, personal holdings increasingly came either from stocks and bonds — that is, a stake in the profits of industrial corporations — or from the salaries and wages of employees. In theory, these forms of (increasingly unequal) wealth should have been an easy target for a federal tax, especially when farmers and consumers from the south and west complained that the burden of those tariffs fell most heavily on them. But rich and powerful folk, obviously, didn’t like the idea of a tax on incomes.

Neither, in the 1890s, did the Supreme Court. Amid a hard depression, an income tax was reinstituted. This time the Court ruled the revived tax unconstitutional because it did not fall proportionately on the states. So the solution had to be a Constitutional amendment, which brings us to two bold Republican presidents and a divided Congress — and one of the great backfires in American political history.

Theodore Roosevelt, who had ascended to the presidency in 1901 upon William McKinley’s assassination, won the office in his own right in 1904. With that added leverage, Roosevelt at first focused on a federal inheritance tax to tap the wealth of the rich. He waited until 1907 to ask Congress for a “graduated income tax” that could pass Court scrutiny. It fell to his successor William Taft first to endorse the idea in his presidential campaign and then navigate a split within his own Republican Party to get Congress to pass an amendment (which would eliminate the constitutionality question).

Taft had doubts, however, that an amendment could actually get ratified by enough states. Republican opponents of the tax seized this eventuality to support the amendment, which now passed overwhelmingly. They figured they could not block congressional passage of an income tax bill, which the Court, reversing itself, might then accept. So the best way to kill the tax was, they calculated, to count on states declining to ratify.

The tactic failed. Ratification came slowly, but it came.

Submitted to the states in 1909, the 16th Amendment didn’t get all the needed ratifications until 1913. By then Democrat Woodrow Wilson had assumed the presidency, pledged to reduce the foreign tariff. Coupled with tariff reduction came the first federal income tax, now legal. Evidently it was seen not as the tool for social change — for income redistribution or funding government social programs — that it would become, but merely as a substitute for reduced tax revenues.

And in fact its impact was quite modest at first. But it became the prime source of federal revenues when foreign trade (and thus tariff income) dropped during the First World War. Since then, the tax — a product of the people’s progressive demands — has burgeoned in impact and complexity.

And controversy. It has made possible the modern welfare state. As historian George Mowry observed, “The modern democratic social service state, in fact, probably rests more upon the income tax than upon any other single legislative act.” Thus supporters applaud and seek to further soak the rich; dissenters criticize and seek to slash the burden. But all lament the convoluted system that has evolved.

As someone has wisecracked, if you thought “taxation without representation is tyranny,” what must you think of taxation with representation!

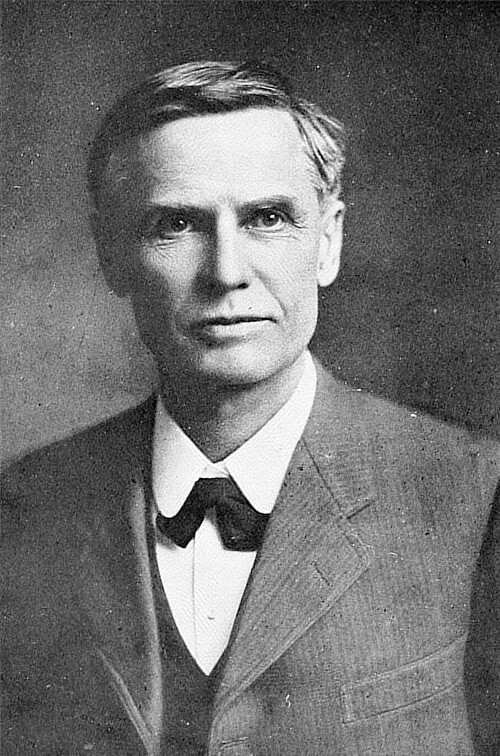

William U’Ren

17th Amendment (1913): Direct election of senators

Progressive reform was as bottom up as top down. Fast on the heels of the income tax came another transforming procedural reform: the election of senators by direct vote. Approved by Congress in 1912, the 17th Amendment sailed through the state legislatures and gained ratification just two months after the 16th.

The Framers of 1787 had envisioned a two-house Congress modeled on colonial legislatures (themselves rough parallels to the British Parliament). The “lower” chamber, like the House of Commons, should be the “people’s house” — representatives of those who elected them. They would serve just two years before standing for re-election. By contrast, senators, serving six years, would constitute a more deliberative, less populist-oriented body. They would be the “best men” of their states, the most educated and cosmopolitan, picked from the “better sort” of society, akin to the House of Lords. The Framers decided they should be selected by state legislatures, rather than by citizen vote, thus shielding them from popular whim and passion.

A famous episode can illustrate. It might be recalled that Republican Abraham Lincoln challenged Illinois’ Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas in 1858; Lincoln and Douglas squared off in a legendary series of debates. Not so well known is that their campaigning was designed not to garner votes for themselves, but to win legislative seats for their respective parties. More Democrats won legislative races, so the party’s majority in Springfield sent Douglas back to Washington, D.C. (Lincoln would have to wait two years to get there, when he beat Douglas for the presidency.)

This system prevailed into the 20th century, despite increasing discontent due to boss rule over state legislatures and even deadlocked bodies that left seats vacant. But the Progressive impulse to hold government accountable — at all levels — impelled state-level campaigns for more democratic processes. The insulation of senators from the popular will increasingly seemed obsolete.

Oregon led the way. There a long-forgotten reformer from the long-defunct Populist Party, William U’Ren, spearheaded a “Direct Democracy” movement, artfully persuading state legislators to accept new tools. His efforts pushed through such innovative devices as the initiative (the people could directly enact laws) and referendum (the people could directly decide if a legislative bill should be passed). U’Ren’s centerpiece was finding a way to choose senators directly. He first angled to get the parties to agree to elect whichever candidate won in a straw vote, regardless of who controlled the legislature. But that sly bypass tactic became unnecessary when Progressives nationwide caught U’Ren’s vision.

Other states followed Oregon’s lead, so that by 1912 a number of first-term senators had won their seats through direct election. They proved enough to break Senate resistance to a Constitutional amendment. (The House had passed draft amendments several times already.) Once the Congress settled on the final text, the states quickly ratified.

For better (fewer corrupt deals in the legislatures) and for worse (less state leverage over Congress), the 17th Amendment meant that all national legislators since 1914 have been chosen by popular vote. Now it is only the president who can win without getting the most citizen votes — as the results in 2000 and 2016 showed, and my pre-election essay of a year ago imagined.

A Progressive constitutional legacy

Progressive reforms extended far beyond changes to the Constitution, of course. But all reflected the common impulse that Progressives wanted to make government more responsive and efficient, and then to mobilize government to fix society’s ills.

That impulse would lead, several years later, to two more Constitutional amendments addressing two dominating social concerns. One was the scourge of drink, the other the exclusion of women from the voting booth. Though it sounds odd today, both were broadly supported by Progressives, because both used government as an instrument for engineering a better society.

Indeed, precisely 100 years ago that spirit expanded to an effort to making a better world — to intervene in the Great War in Europe to make the world safe for, yes, democracy. But that dream and its death are parts of a quite different story.

It’s a story relevant in one crucial sense, however: in the wake of the Great War came Prohibition and women’s suffrage — to be detailed a year hence.

The women’s suffrage movement mobilized women to march for the right to vote.