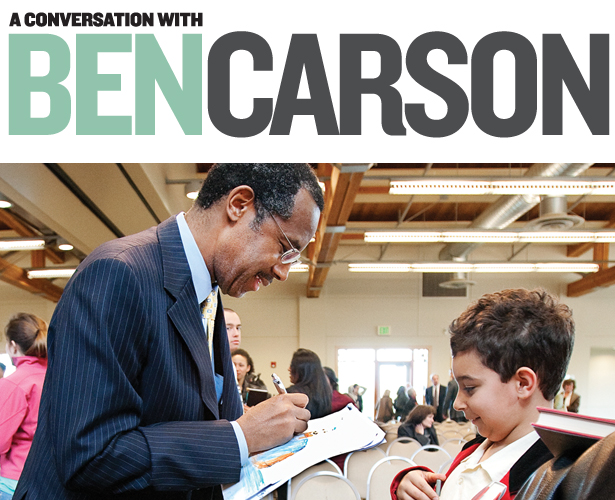

At a midday address on SPU's campus, Carson spoke about the power of determination, autographed a drawing from a young fan, and fielded questions from a capacity audience of students, faculty, staff, and community members. His best-selling book: Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story chronicles his rise from poverty to prominence.

Interview by Clint Kelly (ckelly@spu.edu) | Photos by Mike Siegel

Tell me about The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Why did you choose to work there?

Johns Hopkins is consistently ranked the No. 1 hospital in the country, and it's a place that I heard about even when I was a little kid growing up in Detroit. It was always my desire to work there, so dreams do come true.

When I was on the road interviewing, and I went to all the top programs, I was very impressed by how down-to-earth people were at Johns Hopkins. They didn't seem to be full of themselves. And I have found that to be the case in the 33 years that I've been here. It's easy to work with people, to collaborate with people; they don't try to stab you in the back, and it makes for a very collegial working environment.

Why did you select pediatrics as your specialty?

I started out as an adult neurosurgeon, actually, but I discovered after a while with peds, you can spend a very long time and a lot of effort working on a kid, and, if you're successful, they have maybe 50, 60 more years of life. You don't tend to get that with the adult population, so you get a big return on your investment with kids.

Last year I was in Oklahoma giving a talk, and a family came up to me and said, "Do you recognize this young man?"

I didn't recognize them, I had to confess. So I said, "What's his name?"

They told me his name, and I remembered it. He had been operated on at another university, and they told the family he had less than six months to live. I operated on him when he was 6 months old. Now he is 20 years old. He's in college doing perfectly well. Those are the kinds of things that really make it worthwhile.

You seem to bring hope to families where other doctors might have given up. How do families factor into your health care decisions?

First of all, the patient's care is never just my decision, because I make sure I discuss these things thoroughly with families, and we make sure that everybody's on the same page. That way, if things don't turn out the way we want them to, everybody absolutely knows why that course of action was taken and is in agreement with it and feels good about at least trying. In cases where it is clear that you're not going to have a good outcome — somebody, for instance, who has a glioma of the pons (a type of tumor located in the brainstem) — you're not even going to talk about trying to take that out. It's not going to work.

You've undoubtedly seen "hopeless cases" in your career, and you might have even been considered something of a "hopeless case" yourself as a child, when you were heading down a wrong path. What do you think about the word "hopeless," especially in terms of a young person?

I think "hopeless" means different things to different people, and I think one of the reasons that God gave us these incredible brains is so we could think beyond what some people think is hopeless. If we always stopped because something's not been done before, I guess we'd still be pushing rocks around in caves.

I think if you'd talked to somebody about me when I was in the fifth grade and said, "See that kid? He's going to be a brain surgeon," you would have laughed yourself into oblivion. You just would have said, "That's so ridiculous. Why would you even say something like that?"

Where does your personal hope come from?

First of all, I have a lot of faith in God, and I always ask him to give me wisdom, but I also have a lot of faith in people and in human potential.

I'm also a great student of history. I like to look particularly at situations that are seemingly impossible. For instance, you look at the founding of this nation, when a bunch of ragtag militiamen running around with rags on their feet because they didn't even have boots defeated the most powerful empire in the world. People would say that's impossible, and yet, here we have this nation.

"70 to 80 percent of high school dropouts are functionally illiterate. So we've got to find a way to truncate that upstream."

I've been told that you pray before surgery. What do you pray?

I ask God to give me wisdom, because I believe God is the source of all wisdom.

I also think God has a sense of humor, to be quite frank with you, because I start each day reading from the book of Proverbs, and I end each day reading from the book of Proverbs — which of course was written in large part by Solomon.

Now, how did God know I was going to have this tremendous affinity for Solomon? My middle name is Solomon. How did God give my parents the idea to give me that middle name?

Also, when Solomon became the king of Israel, the first deed that brought him great fame and acclaim was when the two women came to him claiming to be the mother of the same baby. What did he advocate? He said, "Divide the baby." And that's when I became very well-known, when I divided babies. So I really think the Lord has a sense of humor.

Why did your mom insist you buckle down and get an education? What inspired her to do that?

She worked as a domestic, and she saw some of the people she worked for and how successful they were, and she noticed that they spent a lot of time reading and planning and strategizing. And she noticed that in the neighborhood where we lived people spent a lot of time drinking alcohol and sitting around, watching television, talking, and doing silly stuff. She said, "You know what? I think there's a correlation here."

Is there a secret to overcoming adversity, as you did?

Everybody has adversity. I don't care who you are, you've got adversity. Even Bill Gates has adversity, and really, success or failure is determined by how you relate to that adversity. If you decide that it's a continuing fence, it becomes your excuse for failure. If you see it as a hurdle that you have to get over, and you learn how to jump over hurdles, each hurdle strengthens you for the next one.

How important was education in your life, and how important is it in shaping the lives of young people around the country?

I think education is one of the most critical things, because it empowers you enormously. It made the difference between me ending up as a factory worker in Detroit or a hoodlum on the street and being director of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins. I would have had the same brain and the same body, but education was the thing that made the transformation.

How do you see education relating to the health of our country?

Look at the tremendous dropout rates that are occurring in some of our large cities. Look at my hometown of Detroit. The high school graduation rate is 25 percent. In some of our other major cities, it's 30, 40, 50 percent.

Think about this. For every single one of those young dropouts, what are the implications for our society? If we can stop that from happening, that's one less person we have to be afraid of, one less person we have to protect our family from, one less person we have to pay for in the penal system or the welfare system, one more tax-paying productive member of society, who might come up with a new solution for energy or for AIDS.

We can't afford to throw any of them away. They are all vital parts of the fabric and the strength of our nation. And when we allow this to happen, we are weakening the nation's immune system.

What are your goals for the Carson Reading Project and the Carson Scholars Fund?

As far as the Reading Project is concerned, you have to recognize that 70 to 80 percent of high school dropouts are functionally illiterate. So we've got to find a way to truncate that upstream. In most large cities, elementary schools and many middle schools don't even have libraries. So we started putting these reading rooms in schools. They're fancifully decorated places that no kid would pass up, and kids get points for the amount of time they spend in there and the number of books they read, and they can trade those in for prizes. Now, initially they do it for the points and the prizes, but it doesn't take long before that translates into much better academic performance, which is the goal.

Regarding the Carson Scholars Fund, there was a survey done in the early '90s looking at the ability of eighth grade equivalents in 22 countries to solve math and science problems. The U.S. ranked number 21 out of 22. My wife and I became very alarmed, so we started giving our scholarships to students starting in the fourth grade for superior academic performance and humanitarian qualities. If they didn't show that they cared about other people, they didn't get a scholarship. You can't just be smart and not care about anybody else.

We gave out 25 scholarships our first year. We now have over 4,200 scholarships in 42 states. In many high schools, all the hoopla is around the all-state basketball player and the all-state wrestler, and no one cares too much about really smart kids. With the Carson Scholarship, the school also gets a trophy every bit as impressive as any of the sports trophies. It goes right out with the sports trophies with the name engraved of the scholar. They get to wear a medal. They go to banquets. They get local press attention, and we put them on the same kind of pedestal as athletes.

These programs have been operating for 14 years. What effects have you seen in that time?

Many teachers have told us that when we put a Carson Scholar in their classroom, the GPA of the whole class goes up by as much as a whole point over the next year, because now the kids have something else to focus on. They begin to realize they can get just as much attention for solving a quadratic equation as they can for shooting a 25-foot jump shot. Those are the kinds of things that will strengthen our nation.

Do you think this kind of leadership will ultimately make a difference in solving difficult problems like the health care crisis?

Before Medicare and Medicaid, virtually every doctor had 10 to 20 percent of their patients as charity cases. It was an unspoken rule in medicine. You took care of the poor. You took care of the indigent. Of course they had the ability to do that in those days, because the insurance companies would pay. But the point is that people in the past in this country have cared about each other, and if we want to regain the splendor of our past and begin to continue to progress in a special way, we have to recapture that. It's absolutely essential.

My greatest satisfaction is knowing that we've got multiple thousands of incredibly smart kids who also care about other people. We're going to begin to network them together so that we can create the kind of leadership for our nation that will save us: ethical, smart people who care about others. That's what we need.