Arts & Culture Faithful Creativity

Work at the Movies

Beyond Office Space

By Jeffrey Overstreet (jeffreyo@spu.edu) | Photo courtesy of New Yorker Films

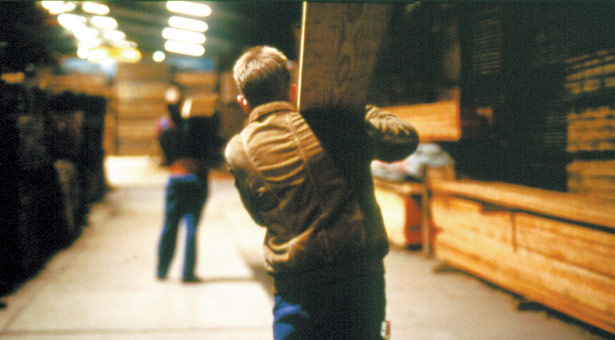

A boy learns a new trade — and much more — in The Son (Le Fils), a 2002 film that Roger Ebert named among the "best of the decade."

Most movies focus on what happens beyond the main characters' workplace. Romance! Adventure! Crisis! Few films pay much attention to the daily routines, the dignity of work — perhaps because work can seem like a boring subject. But thoughtful, observant movies can make the subject inspiring. Here are some memorable — and sometimes overlooked — films that find honor, drama, suspense, and inspiration in the workplace.

Fast, Cheap & Out of Control (1997)

In his documentary Fast, Cheap & Out of Control, Errol Morris interviews four subjects: a lion tamer, a robot builder, an expert on the naked mole rat, and a topiary gardener who prunes bushes

into the shapes of animals. As they share their stories, we discover remarkable correlations and

contrasts between their experiences and perspectives. They're just talking shop, but they're really speculating about life — its purpose and meaning, its driving forces, its origins, and where it is going. All four experts work with maddening constraints and face formidable obstructions. All of them are powerful observers, learning through trial and error. Each expert shows us the tools of the trade that give them a measure of control over their subjects — chairs, whips, computer codes, electricity, cameras, environmental controls, shears. Each is confronted by elements that remain beyond their control and strive to describe the relentless mystery at the heart of their work.

The Son (2002)

In the Dardenne brothers' film, The Son (Le Fils), a carpentry instructor named Olivier becomes intensely interested in one of his students — a young, despondent boy. What seems at first to be a sinister impulse is revealed to be a desire for healing and reconciliation. The teacher's journey from a dutiful instructor to a “good shepherd” makes every exercise in the carpentry shop an eloquent metaphor. As he carefully trains the boys in the importance of exactness, of cutting things “just so,” and making sure the lines are straight, Olivier is really speaking to them about their lives. As he carries heavy beams around the shop, he is giving us a picture of the hard work of bearing one's moral responsibility and, beyond that, taking and bearing someone else's cross.

Norma Rae (1979)

Sally Field won a Best Actress Oscar for her lead role in this story about a textile mill worker who stands up against tyrannical management to protest dehumanizing working conditions. Thirty-two years later, the film remains timely and inspiring. Norma Rae Webster, played by Field, is a spirited worker and single mother. Spurred by a labor union organizer, Norma Rae risks everything to rally

her co-workers to stand up for decency, fairness, and human rights. Compared to today's fast-paced thrillers, the film's patient storytelling builds suspense even as it develops nuanced characters. In its ambitious consideration of relationships, Norma Rae finds meaningful connections between the contracts that companies make with their workers and the contracts that

men and women make with each other and their children.

The Big Kahuna (1999)

Larry (Kevin Spacey) is an accomplished salesman of industrial lubricants. On a business trip to Kansas, he faces one of his most maddening challenges: Bob, his evangelical Christian co-worker (Peter Facinelli). As Larry becomes obsessed with landing an important client, Bob engages in zealous salesmanship for something else: the Gospel. The third member of their team, Phil (Danny DeVito), steps in to referee, trying to help them control their passions and work together. As Phil counsels Larry on how to cope with Bob's “sales pitches,” the movie raises questions about passion, work, faith, and the ways in which we play games with each other in order to achieve desired results. We have so much to teach each other, but if we are not open to hear what others have to say, we will not be very welcome to share with others.

Time Out (2001)

Vincent (Aurelien Recoing) has had enough of the workaday world. Though he pretends to everyone — including his family — that he is still showing up at the office, every day is a new adventure of spontaneity and discovery: driving alone through the French countryside, watching people, taking naps in hotel parking lots, spying on schoolchildren at play, or watching office buildings full of oblivious employees. Time Out is a movie about work and about the damage that routines and conformity can do to us; it is also about the destructive desire to break free of our commitments. We don't want Vincent to succeed in his deception, because it is destroying his beautiful family, his friendships, and his best chance to know and give love. But we don't want him to confess, to shape up, or to get another job, either — the workaday world can be its own kind of nightmare. Which nightmare is worse?

The Insider (1999)

In view of the recent scandals involving Jerry Sandusky at Penn State University, perhaps it's time to revisit The Insider, a powerful and persuasive portrait of a whistleblower. Based on the true story of Jeffrey Wigand, who testified against Big Tobacco, Michael Mann's movie is excruciatingly suspenseful, and it features Russell Crowe, Al Pacino, and Christopher Plummer in exemplary performances. Dividing the story between Wigand's crisis of conscience and the efforts of 60 Minutes producer Lowell Bergman to get the story, the film exposes corporate America's control over the media and the brazen deceit of tobacco companies in creating addicts of their customers. This is a war movie. The big strikes are lawsuits. The battlefields are men's consciences. And the heroes are putting themselves on the front lines for the sake of telling the truth. The casualties? Integrity and reputation. Family. Lifestyle. Futures and dreams.