| Flight Into Eternity

His Hatred Turned to Love,

Alumnus Jake DeShazer Fought

for the Hearts of His Enemies

A friendly, soft-spoken man with a degree in

missions from Seattle Pacific College resides in Salem, Oregon, and turns 92 this year.

In what seems to him like another life, Jacob Daniel DeShazer flew with the Doolittle

Raiders in World War II, bombing Japan in response to

that country�s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

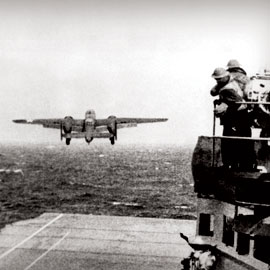

Bombardier Jake DeShazer�s B-25 bomber

was the last to take off from the lurching deck of the U.S.S.

Hornet. Ahead lay the enemy territory of Japan. Bombardier Jake DeShazer�s B-25 bomber

was the last to take off from the lurching deck of the U.S.S.

Hornet. Ahead lay the enemy territory of Japan.

|

|

Scholars

say the Doolittle Raid

was a significant turning

point in the war, an

action that demoralized

the Japanese while bolstering

American resolve. For

DeShazer, it was the

beginning of a long

nightmare that ended

in one of history�s

most remarkable awakenings. Had Corporal Jake DeShazer been a gambling

man, he could have seen

the cards stacked against

him from the start. President

Franklin Roosevelt had

ordered an air assault

on Japan four months

after Japanese bombers

ripped apart eight battleships

in a sneak attack on

the U.S. Pacific Fleet,

killing more than 3,300

personnel and wounding

nearly 1,300 more. The

daring and much-decorated

Lt. Col. James H. �Jimmy� Doolittle

was given the command

of Roosevelt�s

top-secret mission. He

came to DeShazer�s

air base looking for

a few good men.

Doolittle was brutally honest: The mission was a dangerous one.

Chances were good that they would be killed. How many would volunteer?

One by one, men said yes, including DeShazer. The farmer-turned-bombardier

admits that he was too much of a coward to say no.

Sixteen Army B-25

bombers and their five-man crews steamed toward the coast of Japan

crammed aboard the U.S.S. Hornet aircraft carrier. Still 200 miles

from the night-launch position, the carrier was spotted by a Japanese

fishing boat, which radioed a warning to Japan. The options were

stark and few. Either the Army planes took off in broad daylight

in gale-force winds, or they would be pushed overboard to allow the

Navy fighter planes on deck to protect the fleet from possible

attack. The call to arms crackled over the loudspeaker. �Army pilots,

man your planes!� The date was April 18, 1942.

Heavy seas broke over the flight deck. Hurriedly, the planes were

stocked with extra gasoline for the flight into unknown territory.

Once airborne, the airmen could not re-land on the carrier, and

they did not know how far their fuel would take them.

The roar of

the aircraft was ear-splitting. DeShazer�s overloaded plane — #16,

Thunderbird Squadron — was the last one off the carrier.

Like his colleagues, the pilot timed his launch to coincide with the rising of

the bow to ensure maximum lift.

Once successfully in the air, DeShazer moved

into position in the nose of the plane. He knew there was a jagged 1-foot hole

in the bomber�s plastic windshield, but he�d kept that information to himself

for fear their part in the mission would be scrapped. Drag from the open hole

slowed the plane�s air speed, and #16 soon fell behind.

Their target was the oil storage tanks at Nagoya, 300 miles south of Tokyo.

Flying at 500 feet, DeShazer dropped 2,000 pounds of incendiary bombs. He scored

a direct hit, but smelled the smoke of return fire as enemy shells exploded

around him. Payload delivered, the plane flew on toward China.

A night of heavy fog enveloped the five men in bomber #16 as they tried desperately

to get beyond Japanese-held territory. Dangerously low on fuel, they circled

a town, hoping to spot an airfield where they could land. But after nearly 14

hours in the air, the fuel gauge warning light flashed red, and the pilot said, �We

gotta jump.�

The crew parachuted into darkness and was separated. DeShazer remembers landing �with

an awful jolt� on top of a grave in a cemetery, fracturing some ribs. His mother

in Oregon awoke suddenly during the ordeal and felt compelled to pray for him.

The next day, after several hours of painful walking, DeShazer was surrounded

by 10 Japanese soldiers armed with bayonets, pistols and swords — and thus began

40 months of torture and imprisonment, 34 of them in solitary confinement.

Of DeShazer�s crew, all were captured. The pilot and the engineer gunner were tied

to small crosses and executed. Beatings, fear of execution, starvation rations,

severe dysentery and delirium became the grim companions of those left alive.

The only source of strength DeShazer knew in his tiny cell was a bitter hatred

for the enemy.

But back home, people were praying. When erroneously informed

by the U.S. Army that all of the captured airmen had been executed, DeShazer�s

mother replied, �I have word from a higher authority that my son is still alive.� Her

faith was rewarded. Secretly, Japanese Emperor Hirohito commuted the death sentences

of the remaining captives for fear of U.S. retaliation.

DeShazer had always kept

his parents� Christian faith at a skeptical distance.

Brutal treatment at the hands of the Japanese

further hardened his heart. But after two long years of captivity, a light began

to dawn in his soul. Fellow prisoner

Lt. Bob Meder reminded him that God

was in control and that Jesus Christ,

his son, had died for all of humanity.

When Meder died of slow starvation, DeShazer pondered what made people hate one

another. He thought of the claim that Christianity could change hatred into love

and was gripped with what he later called

�a strange longing� to read the Bible.

Incredibly, the Japanese supplied the

airmen with a copy of the Bible in English.

As starved for truth as he was for food, DeShazer devoured the Scriptures. For

hours, he read and marveled at the redemption he found there, and at the admonitions

to forgive and love one�s enemies. On June 8, 1944, he read Romans 10:9: �If

thou shalt confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus and shalt believe in thine heart

that God hath raised him from the dead, thou shalt be saved.� It was then that

the emaciated Doolittle Raider asked God to take command of his life. �My heart

was filled with joy,� he says. �I wouldn�t have traded places with anyone.�

Bob Hite, now 84 and copilot of DeShazer�s crew, recalls the transformation that

Bible brought to them all, especially to his bombardier: �Jake was in a cell

adjoining mine. Whenever we wanted to communicate without the guards knowing,

we�d knock on the wall, �Shave and a haircut, six bits.� That was the signal

to go to the toilet, lift the lid, and speak into the john. Our voices carried

through the plumbing.

�One morning early, I knocked but got no response from

Jake. I was worried. Hours went by and no word. A guard and a supervisor yelled

into Jake�s cell to get his attention. Nothing. Finally, seven hours later, at

around two in the afternoon, I heard a knock. I asked him what in the world happened.

He said, �I was praying, and the Lord revealed to me that the war will end today.

We will not be shot. We will be released.� That was August 10, 1945, the day

the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.�

DeShazer wasn�t quite finished explaining what he had heard. �God wants me to

come back and preach the gospel to these people,� he said.

Ten days later, American paratroopers landed on the prison

grounds and liberated Doolittle�s men. In all, eight men from two Doolittle bombers

were taken prisoner. Three were executed; one died of starvation; and four survived.

Back

in the States, the rescued Raiders were big news. The normally reticent DeShazer

was thrust into the headlines and onto the radio. He was swamped with requests

to speak at churches and youth rallies. Inevitably, some thought his decision

to return to Japan as a missionary would be short-lived. Others questioned his

motives. When he called the parents of one of the executed airmen to express

sympathy, he was told not to call again.

But no one should have underestimated the effect of DeShazer�s decision on the rest

of his life. He believed he had been spared for a purpose, and no power on earth

could deter him from it. At age 33, the newly discharged airman was resolved to

obtain his college degree and leave for Japan as soon as possible.

Soon he was receiving catalogs from

dozens of colleges across the country hoping he�d enroll in their missions programs.

Helen Andrus, DeShazer�s half-sister, was secretary to C. Hoyt Watson, president

of Seattle Pacific College. Watson extended a personal invitation to DeShazer

to attend SPC and, just two months after his release from prison, he was in the

classroom. He says he grew in spirit and understanding, and felt �as if I had

come in from a howling windstorm into a good strong house.�

It was at SPC that

he met junior Florence Matheny. Today, after nearly 58 years of marriage, Florence

recalls, �I already knew I had a call from the Lord to missionary work, just

not where or how. Jake answered that.� A year after DeShazer�s release from prison,

he and Florence were married. Another year passed, and the first of their five

children was born.

His college days were packed with study and speaking engagements.

But six years after DeShazer raided Japan, he walked across the platform in McKinley

Auditorium to receive his diploma from President Watson. Already accepted as

Free Methodist missionaries, the DeShazers set sail for Japan in December 1948.

Japan was abuzz with the news of DeShazer�s arrival.

Crowds thronged his ship at the Yokohama docks. A million tracts containing his

testimony, I Was a Prisoner of Japan, had been distributed ahead of his arrival.

People were curious to see the former P.O.W. and to learn about the love he professed

for his captors. DeShazer preached four or five times a day for the next six

years, and thousands of Japanese became Christians, including two

of his former prison guards.

�My love for the Japanese people was deep and sincere,� says

DeShazer. �I know that it came from God.� And it was mutual. When their son Paul

became critically ill with encephalitis and fell into a coma, he was prayed for

by Christian friends in both Japan and the United States. Though the medical

staff at the U.S. Army hospital had never seen a more severe case of the disease,

the boy recovered completely.

For three decades, the DeShazers lived in Japan,

putting their language studies with SPC Professor Bokko Tsuchiyama to good use.

Where once DeShazer was known derisively as dai-go-go, or Number 5 (for cell

#5), he was now known respectfully as sensei, or teacher. He preached in churches,

schools, hospitals, tent meetings and coal mines. He and Florence helped plant

23 churches, including three from their home, and one in Nagoya, the city that

DeShazer had bombed.

�My dad�s evangelistic zeal just keeps going and going,� says

daughter Carol Aiko DeShazer Dixon. Dixon practiced her student teaching while

at SPU in 1979. Her brother Paul DeShazer graduated from Seattle Pacific in 1969,

sister Ruth DeShazer Kutrakun in 1980.

Until recently, even in retirement, Jake

DeShazer continued to receive frequent invitations to speak and give interviews.

Every April, the surviving Doolittle Raiders hold a reunion, but the numbers

dwindle as the years pass.

The oldest surviving Raider, DeShazer did not feel

well enough to attend this year�s reunion, but he keeps in touch with his Doolittle

brothers. In a glass case guarded by two airmen at the Air Force Academy in Colorado

Springs, there are 80 sterling silver goblets engraved with the names of those

men whose motto was �Ever into peril.� Upon each Raider�s death, his goblet is

inverted. Of the original number, only 17 remain upright.

�We�re not heroes,� the

1973 SPU Alumnus of the Year insists. �We saw a job to do and did it.�

The pace

has at last slowed so that the DeShazers can devote themselves to their children,

10 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. There is a movie about DeShazer�s

life in development, as well as a new book. The first book on his experiences

was written in 1950 by President Watson.

The DeShazer legacy lives on in Japan,

where in 1971 the Doolittle Raider was appointed superintendent of the Eastern

Conference of Independent Free Methodist Churches. Though today only 1�2 percent

of the population of Japan is Christian, many of those can trace their faith

heritage back to the American airman and his wife, who once held children�s Bible

classes in their Japanese home. The DeShazers have returned to Japan several

times to encourage the churches and renew ties with fellow believers.

Dixon has

vivid memories of the Holy Spirit abroad in Japan and her father sharing his

story again and again. As a young child, she was so moved by his conviction that �whenever

my father would give an altar call at the end of his testimony, I was usually

the first one at the altar!�

Florence DeShazer chuckles now at such memories and

marvels over how long she and her husband have been there for one another. �When

I had my two back surgeries, Jake took care of me,� she says, smiling at her

mate. �Now he needs me to look after him.� And after living one of the most amazing

stories to come out of World War II, they definitely know what it is to have

God look after them both. R

— BY

CLINT KELLY

— PHOTO

BY USAF (#41195)

Back to the top

Back to Home |

|

|

|

|

_thum.jpg)