Story by Connie

McDougall

Photos by Jimi Lott

![]()

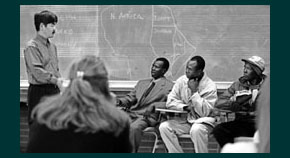

ON A GRAY MORNING during Autumn Quarter 2001, three Sudanese men in their early twenties enter a Seattle Pacific University classroom. Accompanied by Cal Uomoto, director of World Relief's refugee program in Seattle, and their caseworker, Amy Wagner, a 1998 SPU graduate, the young men settle into plastic chairs. They smile shyly at the freshmen, all about their own age, facing them.

The Africans pull off wool hats but retain scarves and gloves. Used to equatorial heat, they are chilled even indoors. Then they speak. In heavily accented but excellent English, they tell a harrowing story — how they survived civil war, marauding lions and refugee camps, and how they have been on their own since the age of seven.

This remarkable exchange takes place in University Seminar, a first-quarter freshman course in the Common Curriculum. University Seminars are designed to orient students to college-level academic work, and each one focuses on a different interdisciplinary topic. In this particular class, called "Beyond Barriers," students are learning from the experiences of people who have overcome obstacles to gain something of great value.

And the freshmen do learn from the Africans. They learn that Joseph, Marko and Anthony are part of an exodus the media dubbed "The Lost Boys of Sudan." It all began in the 1980s, when insurgents from northern Sudan attacked the south. Invaders kidnapped girls, selling them as slaves in the north. Adults were killed or captured. But as many as 12,000 boys escaped, slipping into the jungle and walking barefoot for three months. Those who lived survived hunger, thirst and the unimaginable terror of wild animals.

"The boys walked in a line through tall grass, and lions would come out of the grass and take them," Joseph remembers.

"If you cry and fall down, the animals will get you," adds Marko. "We had to keep walking."

One visiting refugee wants to be a pilot; one hopes to be an engineer or doctor; and one leans toward business. They plan to use their skills to benefit the people of Sudan.

Anthony says that some little boys finally gave up. "They would walk for a while and then sit down. If they sit down, they do not go on."

And yet there were miracles. "Oh yes, this really happened. God protects us from all we went through," Marko explains. "In the desert, there was no water, so a single cloud formed overhead and it rained upon us."

The tribe of children found sanctuary in Ethiopian refugee camps, but four years later, civil war forced them to flee again, chased by soldiers. At river crossings, swimming boys were shot or picked off by crocodiles. Survivors ended up in Kenya, spending nine years in refugee camps while the world debated their future. Recently, the children — now grown men — have been allowed to immigrate to other countries, including the United States. About 50 have settled in the Seattle area.

Wagner, 24, helps them acclimate to an entirely different culture, saying refugees stay with a family for two or three weeks to make the initial adjustment. After that, she and volunteers find housing and jobs for them.

Wagner was thrilled to introduce her "guys" to the University Seminar class, knowing it would stretch both the Africans and Americans. "The freshmen may not really understand all of this, but I know they have a heart to serve the Lord. And it was wonderful to bring the guys to SPU, the place that so shaped my life."

Linda Wagner (no relation to Amy) taught the Beyond Barriers class and notes that student papers reflect a true learning experience. "The most common response was how it opened their eyes. Students were awestruck and felt gratitude for their lives, especially their education."

Freshman Brad Hostak marveled at how important learning is to the Sudanese men, recalling how as boys they carried satchels of books throughout their ordeal. Marko, for instance, brought along his Bible and a math text. Hostak is no stranger to hardship, having survived childhood cancer, yet he is amazed at the perseverance of the "Lost Boys." "Even with an illness, there are times you can relax and rest. They couldn't do that." Another freshman, Jelena Berovic, found personal meaning in their story. She is a refugee as well, from Bosnia. In her reflection paper on the tragedy and triumph of the African children, she wrote with special understanding: "They were just kids, but they had to act as adults … their time of play and laughter was over; their struggle for life had just begun."

![]()

| Please read our

disclaimer.

Send any questions, comments or correspondence about Response to jgilnett@spu.edu or call 206-281-2051. Copyright © 2003 University Communications, Seattle Pacific University.

Seattle Pacific University |