A Leader in His Time — and for All Time

A Conversation With Lincoln Biographer Ronald C. White Jr.

Ronald C. White Jr. Photo by Greg Schneider

Editor's Note: This is the extended version of the Conversation with Ronald C. White Jr.

Interview by Clint Kelly, Response Senior Writer [ckelly@spu.edu]

Leo Tolstoy, Russian author of War and Peace, traveled to a remote corner of Eurasia’s Caucasus Mountains in the early 20th century. There, a Caucasian chief and his neighbors asked to hear about the life of Napoleon.

Tolstoy told the story, but when he had finished, the chief raised his hand: “But you have not told us a syllable about the greatest general, and the greatest ruler of the world. He was a hero. He spoke with a voice of thunder. He laughed at the sunrise, and his deeds were as strong as the rock and as sweet as the fragrance of roses. He was so great that he even forgave the crimes of his greatest enemies. His name was Lincoln. And the country in which he lived is called America.”

The legend of the 16th president of the United States of America –– a self-taught country lawyer who gave his life to emancipate slaves and preserve the American union –– reached the far corners of the earth from the time of his death in 1865. And the thirst for knowledge about Lincoln and his formidable leadership skills continued to show little sign of abating as the bicentennial celebration of his birth came to a close on February 12, 2010. One measure of that interest: More than 17,000 books have been written about Lincoln, with 372 published in the last year alone.

“Transformational leadership” as modeled by Lincoln was the focus of Seattle Pacific University’s 2009–10 Day of Common Learning, October 14, 2009. Delivering the keynote address to students, faculty, staff, and guests was Lincoln scholar Ronald C. White Jr., a Huntington Library Fellow and former dean and professor of American religious history at San Francisco Theological Seminary. His 2009 A. Lincoln: A Biography is a New York Times best-seller, one The Washington Post believes “belongs on the A-list of major biographies.”

White spoke with Clint Kelly, Response senior writer, in a wide-ranging interview about Lincoln as a young man, as a lawyer and candidate for national office, and as president-under-fire during America’s greatest crisis. “Though I don’t think Lincoln can help us solve the problems of climate change or how many troops to send to Afghanistan,” says White, “I deeply believe he can help us understand what leadership can look like today.”

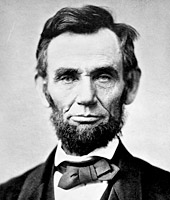

Photo of Abraham Lincoln by Alexander Gardner/Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

|

Lincoln's early years

Q: What aspects of Lincoln’s upbringing shaped the transformational leader that he was to become?

A: Although Lincoln had less than one year of formal education, we need to look precisely at the content of that education. For example, one of the earliest books he ever encountered was Thomas Dilworth’s “speller,” a kind of popular spelling book used in schools in the early 19th century. What has been overlooked is the fact that Dilworth was an English minister and that he was not simply teaching grammar or spelling. He was really offering a moral education.

So when Dilworth comes to tell the student how to form three-, four-, or five-syllable words, every one of his examples is from the Bible, most from the Old Testament, from the Psalms. And so Lincoln developed early this great love of the Bible, especially of the Psalms, certainly the content but also the cadence of the poetry.

Here we see something that the young Lincoln formed and took into himself. And my ultimate question is: How did he develop what I call an “internal moral compass” when so many people, then and now, get their cues from external sources? I think this is one key part of it: that his early education was a moral education.

Q: Were there any other indications when he was young that he held such great potential?

A: The friends of his youth, as they were interviewed shortly after his death, remembered that he was different than they were, that he was a leader. One night he and his friend, James Gentry, were walking home and they heard this moaning by the side of the road, and it was very cold. It was a winter evening, and they saw a man who was lying on the road and obviously drunk. Well, Lincoln put him over his shoulder, took him to a place of shelter, and stayed with the man all night until he was OK to take care of himself.

Looking back, Gentry was impressed; he wasn’t too sure that many other boys or young men would have done such a thing. Again, it was because of a kind of internal moral compass that Lincoln acted instinctively with compassion toward this man. Lincoln was a teetotaler who did not like drunkenness, yet he reached out to this man who was drunk, and he took care of him.

Q: Would you say that as a child and young man Lincoln was something of a loner, or did he always have a lot of acquaintances around him?

A: On the one hand, he was a loner in the sense that he could be alone with his books, with his thoughts. And yet he was a strong, young, masculine fellow and right there with the other boys in the jumping and running contests. He loved a good time. He developed a sense of humor, which I think his father did have and maybe gave to him, and he loved to tell jokes, to laugh, to laugh with other people, to laugh at himself, and this made him a very popular companion.

Q: So he could enjoy his own company as well as the company of others?

A: He could, absolutely.

Q: He certainly experienced both as a president.

A: He did. I think the problem for the modern president is how in the world does the modern president ever find any time to be alone, to think, to brood, to reflect? For Lincoln, that was a lifelong habit, and he carried that into the presidency.

Developing leadership skills

Q: Though he was a farmer’s son, young Lincoln was known for his intellectual curiosity and love of books and reading. In terms of the skills that he displayed later in life — legal skills, debate skills, oratory skills, and so on — do you think they were innate or did he struggle to develop them?

A: Lincoln was not simply some genius who could write or speak at the first stroke. He worked very, very hard on these things. Our grammar books do not usually include what was included in that day. It was called declamation, and at the end of the books, students would be asked to read something out loud from Cicero, from Lord Byron, from Shakespeare, from the Bible. And Lincoln worked very, very hard to master this skill.

Ultimately, other people might have mastered those skills, but it would be the integrity that audiences sensed in Lincoln as he delivered his words that would distinguish him.

Q: How did Lincoln’s difficult relationship with his father affect the man he became?

A: Sometimes we are who we are in reaction to other forces. In Lincoln’s case, part of the conflict with his father was his father’s inability to appreciate the intellectual curiosity of his son and therefore his son’s great desire to read books. He assumed that Lincoln would be a farmer and that he would work the land. So he didn’t understand his son.

The good news was that Lincoln’s mother, even though she died when he was 9 or 10, and then his stepmother, appreciated the talents they saw in Lincoln and were willing to affirm and nurture them.

In terms of faith, Lincoln rebelled, I think, against both the faith and his father’s faith, and it’s often hard to separate the two. His father was active in what was called the Separate Baptist Church and expected his son to be as well. I speculate that Lincoln found this kind of revivalist Baptist faith a little bit too emotional for him. He was always suspicious of emotion, and perhaps it didn’t allow him to ask the questions that he wanted to ask.

So he pushed both his father and the faith away. But then, later on, as is true for so many of us who come back to faith when we become adults and when some crisis enters our life, Lincoln returned to the faith because of the death of his son. But he couldn’t affirm his father’s kind of faith. He had to find a more rational, thoughtful kind of faith.

Q: I think people feel a sense of wonder that someone with such a rough-hewn upbringing could become as erudite as Lincoln did and command an audience the way he could.

A: Well, it’s remarkable. That’s what he campaigned on and what struck people of his day and what I’ve found that people in other countries are amazed by today. Washington and Jefferson, for example, were well-born, well-educated, part of what we might call an early American aristocracy. Lincoln began with none of those advantages, yet he became a very erudite person.

Coming into his own as a leader

Q: Looking at Lincoln’s development over time, how and when do you think he really came into his own as an exceptional leader?

A: Well, Lincoln ran for Congress and was elected and served from 1847 to 1849. He did not consider his term there particularly noteworthy. He had taken a very unpopular stand against the war with Mexico, declaring it an expansionist war, really a war propagated by slaveholders who were ultimately looking perhaps to expand slavery even south into Mexico. He came home recognizing that he did have an unpopular stand, and the person who was supposed to follow him in that district, a fellow Whig, was defeated and Lincoln received part of the blame for the defeat because people were unhappy with him. So he served the next five years as a lawyer, from 1849 to 1854.

I think it happened when he re-entered politics to run for the U.S. Senate in 1854. He emerged from five years of practicing law to fight the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which would have extended slavery into the new Western territories and states. Lincoln believed the American dream was about “the right to rise,” as he had, and he hated slavery because it denied African-Americans that right. Beginning in 1854 we see a Lincoln who had reflected upon the meaning of the American experience — and for the first time began to bring into the national conversation about slavery the Declaration of Independence.

For modern audiences, it’s very important to understand that the Declaration of Independence was not always considered this great document. In the first 50 years of the 19th century, it was viewed merely as a historical signpost. It had worth because it was the document by which we separated ourselves from Great Britain, but that had happened a long time ago.

The proposition “All men are created equal”? Actually, most people didn’t believe that then. Republicans and Democrats in the Senate or the House would say, “Well, that’s obviously not true,” or that Thomas Jefferson had only meant this for white male British citizens. Lincoln believed that “All men are created equal” was a promise not fulfilled fully by the founders, to be sure, but a reforming impulse that could now be fulfilled.

He had a wonderful conversation when someone asked him, “Well, if the founders wanted to make equality their bottom line of the meaning of America, why didn’t they actually fulfill it?”

And he said, “Ah, it’s like Jesus’ words ‘Be ye perfect as your Father in heaven is perfect.’ It is not that Jesus thought we were perfect or are perfect but that this is really a road on which we are to progress toward perfection.”

And so, he said, “We have a chance in our generation to fulfill this more fully than the people in the founding generation.”

Q: It sounds as though he learned from the hard knocks of life and politics in particular. That’s a wonderful quality.

A: Well, that’s true. Sometimes we have mistakenly looked at his law career as separate from his political career. But actually, there were a lot of things that he learned in his law career. For example, his second partner, Stephen Logan, was a former judge, a senior person in the state of Illinois, and he was the one who taught Lincoln that to be a successful lawyer, you must understand your opponent’s case intellectually and passionately as well as he does. If you do not understand and appreciate the point of view of your opponent, you will never be successful.

Lincoln could also appreciate the point of view of those who opposed him. And all of this gets to the heart of his transformational leadership: his ability to understand the point of view of the other, and not just understand it but appreciate it. This is what is so missing in today’s politics.

Lincoln tried very hard to appreciate even Stephen Douglas, who he debated. He would try to understand what Stephen Douglas was appealing to, and he would give it its day in court, so to speak, and then make his own point. So I think transformational leaders appreciate the points of view of even those who oppose them.

Q: I do find so frustrating the tendency between the two major parties to cast the other as completely wrong, completely evil, so it’s such a sweeping generalization.

A: It is. And unfortunately, that’s being carried over by talk shows, by the general public. I find myself saying recently that I will only listen to a conservative columnist or person who is able to see some good in a liberal position. I will only listen to a liberal who is able to see some good in a conservative position. Otherwise, there’s no point in listening.

Q: Yes, that’s very true. I don’t know how we can break out of that mold.

A: It’s very tough, and I think changes in media add a whole new dimension. In Lincoln’s day, the newspapers were terribly political, even more political, really. The Chicago Tribune was Republican, The Chicago Times was Democratic and you knew that. Yet they didn’t have the same kind of power, I think, as talk shows and 24/7 television programs where people are shouting at each other.

Q: There were some mighty nasty editorial cartoons about Lincoln, though.

A: Absolutely. Lincoln was called the original gorilla. He was called a baboon. He was called the black Republican, a nigger lover. I mean everything under the sun. I’m not in any way dismissing that. It was very vitriolic.

Humility and ambition

Q: It’s often said that a powerful leader has both humility and ambition. Do you think both need to exist in a great leader?

A: Which was the more useful trait for Lincoln? I think they both need to be present and were in Lincoln. He was a very ambitious person. I suggest early in my biography that one of the tasks of his life was that he needed to learn how to prune the branch of ambition in his tree of life so that it did not grow out of proportion to the rest of his life.

He also, early on, called himself “humble Abraham Lincoln” and is called that by others, and obviously that’s a quality that we see later in his life. I think it can be a quality that is a part of a maturing, mellowing process in people. I find this remarkable in the last two great speeches of his life, the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural Address. In the Gettysburg Address there are no personal pronouns, none, and in the Second Inaugural, only two. Contrast that with the modern politicians where their favorite word is I, I, I. So Lincoln is, again, pointing beyond himself.

So it’s a delicate balance between ambition and humility, and I think one way to judge any politician, past or present, is to ask how they balance it. How do they keep the ambition in check?

For example, Lincoln, a Republican, ran for the Senate in 1855 when it was still a position elected by the state legislature. After the first six or seven ballots, he was in the lead, but he couldn’t quite get the right number of votes. So he decided to withdraw from the contest and allow a Democrat to win, because the Democrat was against the expansion of slavery, and the Republican candidate who might win would be for slavery. He was willing to step back and toss his votes to an opponent from another party because the opponent shared a basic idea with him: Let’s stop the westward spread of slavery. That was a big moment, I think, in Lincoln’s life.

Q: That’s amazing.

A: That evening, there was a reception that had been planned to honor Lincoln, because everybody assumed he’d be elected. Well, this other fellow was elected, and Lincoln showed up at the reception. And the host said, “My gosh, I’m pretty surprised that you’re here.” “Well,” he said, “I’m here to congratulate Lyman Trumbull, who won the election this afternoon.”

The "big-tent" concept

Q:

In the 19th century idea of the self-made man, was there any sense in that day of “Nobody owns me?” We’re really big these days on saying, “Well, I’m not beholden to this corporation or that —”

A: Yes. Quite honestly, the idea of the self-made man was a great, attractive idea in the 19th century. They didn’t mean, as we often do, “self-made” as an economic term. No, “self-made” meant a fully developed individual. And Lincoln did want to seize upon this idea.

We have to keep in mind Lincoln’s ideals or idealism and also a critique from Sean Wilentz, professor of history at Princeton University published in the New Republic early last fall. Wilentz was critical of some of the Lincoln books of 2009 because they didn’t lift up the fact that Lincoln, in addition to his idealism, was a very shrewd politician. He knew how to work the Republican machine. He knew how to get the votes. He knew how to play hardball in a certain sense. So the two are not necessarily opposed to each other and Lincoln was a very, very skilled politician.

Sometimes it’s been suggested that this man came to the presidency from nowhere, but that’s not really true. He had been a member of the Illinois Legislature four times, a United States congressman one time. He had run for Senate twice. He was a skilled and experienced politician. He had never served in the United States Senate, but he was not someone who just came from nowhere.

Q: A transformational leader, by definition, brings different people together. Was Lincoln himself humble enough to admit when he was wrong and to listen to other people’s ideas?

A: One way to answer that question is by talking about one of the problems that Lincoln had in Illinois in the late 1850s and even when he ran for president in 1860. A lot of powerful people were allied to Lincoln; a lot of them thought well of him. They thought he had a chance to become the president, but they didn’t get along well with each other. There was a lot of internal squabbling and bickering among them. Lincoln’s skill was to keep all of these people together, moving forward to a common goal.

It’s the “big-tent” concept that I think is being forgotten today. He had supporters who were liberal. He had supporters who were conservative. He had supporters who were longtime Whigs. He had supporters who were longtime Democrats now become Republicans. And he recognized that all these people had something to contribute and affirmed them.

Q: That’s such a problem today. We don’t think we have anything to learn from each other.

A: No, we don’t, and so the Republican Party is becoming the party of kind of conservative purity, and the Democratic Party has the tendency to become a party of liberal purity. Republicans have a hard time with moderates; Democrats have a hard time with moderates or conservatives within their own party. And this wasn’t even the case 50 years ago. Both parties were much more big-tent parties 50 years ago. You had a lot of liberal Republicans, and you had a lot of conservative Democrats.

But there’s a tendency to purge these people from the party, and Lincoln didn’t want to purge these people from the party. He recognized the Republican Party needed all these people.

Q: Could you cite one example of a time when Lincoln made a decision that risked making him unpopular?

A: Yes, in the very first days of his presidency. The day after he was inaugurated on his first day in office, March 5, 1861, he arrived at his office and received a letter from the commander at Fort Sumter saying, “We can only hold out for six more weeks and then our supplies will be gone.” And Lincoln was confronted with the question: Should he resupply Fort Sumter?

So as a man of deference and respect, he called his cabinet together, remembering that his cabinet was made up of four of his chief rivals who were more experienced than he was, and he took a vote. And the vote was 6–1 not to resupply Fort Sumter. They couldn’t do that because it could be considered an act of war.

He then called in his generals, and he brought in Gen. Winfield Scott, a 75-year-old hero of the War of 1812 and the war with Mexico, and he said, “General Scott, what do you think?”

“Well,” he said, “It would take us eight months, and we’d have to raise a huge army to resupply Fort Sumter, and even then, I’m not sure we’d be successful.”

So Lincoln kept asking, because he started out with deference and respect. But five weeks later, he made a decision against all of these pieces of advice to resupply Fort Sumter. So this is an example of him listening to advice and being willing to go forward with what is in a real sense a minority opinion. But he was the president. He understood himself as commander in chief, with the ability to do what he believed was right.

Confidence in his own abilities

Q: That takes a real sense of confidence in one’s own ability to synthesize facts and opinions and then make a good choice.

A: It does. He took a vote, but at the end of the day, he did what he thought was right against almost overwhelming opinion on the other side.

Q: Could you cite an example of a time when Lincoln changed his mind or his direction because of new information or a change of heart?

A: Well, a great example of this is the long, long battle [during the Civil War] led by Ulysses S. Grant for Vicksburg. Vicksburg often paled in the public eye compared to Gettysburg, but Grant understood that Vicksburg was at least as important as, if not more important than, Gettysburg — because if the Union could seize Vicksburg on the Mississippi, they would divide the Confederacy into two parts. So when the Battle of Gettysburg ended on July 3, 1863, and Vicksburg surrendered on July 4, 1863, it was the turning point of the war. A few days later, Lincoln writes a letter to Grant.

He begins by saying, “Dear General Grant, I don’t believe we’ve ever had the privilege of meeting. I simply want to say to you that when you decided to do this, I thought you were wrong. When you moved into Mississippi, I thought that was a mistake.” At the end of the letter, he says, “General Grant, I simply wish to say I was wrong and you were right.”

Q: Wow.

A: He’d written a letter and said, “Congratulations, General Grant.” But he goes out of his way to say, “I was wrong. You were right.”

Q: Is that a sign of a transformational leader?

A: Yes, I think it is. Today, we have the term “flip-flopper” that grew out of the John Kerry campaign four years ago. Well, you could say Lincoln was a flip-flopper. He had the ability to change his mind when new facts or new circumstances arose, and the ability to change one’s mind is part of transformational leadership.

I think there’s a difference between idealism and ideology. Ideology, “We must never raise taxes,” is fixed. Idealism, “This is our basic goal,” can be changed. The particular outcome of that idealism can change when the facts or the circumstances change. Lincoln was heard to say one time, “My policy is to have no policy.” Now that didn’t mean he didn’t have ideals, he didn’t have values, but he recognized that the Civil War was a moving target, and he had to change his policies as things changed.

The Emancipation Proclamation

Q: Must transformational leaders, in order to bring transformation, be likeable people?

A: They should be likeable in the sense that they get along with others but are also willing to take a courageous stand, as in Fort Sumter, and to take the criticism. Lincoln was severely criticized.

For instance, why didn’t Lincoln move more quickly towards emancipation? Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the abolitionist senator, was always sort of on Lincoln’s case for not moving more quickly. And one day Lincoln said to him, “Senator Sumner, you and I have exactly the same ideas about emancipation. We’re simply operating by a different clock.”

So Lincoln said, “I’d like to have God on my side, but I need Kentucky.” The lynchpin of all this was he knew he had to keep the four border states, Maryland, Missouri, Kentucky, and Delaware, on his side. If two or three of those states were to move over to the Confederacy, the cause might be lost. He couldn’t move too quickly, or he would alienate those states. That made him appear too slow to many abolitionist-leaning senators and leaders. But he tried all the options. He told them, “I will offer you compensated emancipation. I will pay you to emancipate your slaves.” And finally he said, “And you can emancipate them all the way up to 1895. You can do this gradually.”

When they rejected the idea in early July of 1862, he said, “OK, then we’re going to move forward to a general emancipation. I’ve given you every opportunity to do this in a gradual way, but you will not take the opportunity, so we’re going to go forward with the Emancipation Proclamation.”

Q: With so much division in the nation leading up to his taking the office of president, why do you think America chose the somewhat rougher, backwoods person over a more polished rival or someone else who might have seemed more accomplished or more experienced?

A: Well, two reasons. Americans in the 19th century often chose what they sometimes called the available candidate, by which they meant that some of the well-known leaders of the party had also bigger targets, and there was a lot of antipathy toward them. I think this was true in Lincoln’s campaign in 1860. So for example, William Seward from New York was the best-known, and he led on the first two ballots in Chicago in 1860, but there was feeling against him. He was too radical in terms of slavery. He was a divisive figure. Salmon Chase of Ohio was a very able man, both governor and senator, but he was too ambitious.

There had been a series of kind of middling presidents who turned out to be middling presidents because they were the second or third choice in the 1840s and 1850s, because the first choice had too much opposition. Lincoln didn’t have all these oppositions against him, and very shrewdly, his campaign was run by suggesting to voters, “If you need to turn away from Seward or Chase or Bates, could you consider me as the second choice?” By not saying, “I am better than Seward. I am better than Chase,” he made himself an easier person to turn to.

Secondly, as Aristotle suggested in his Treatise on Rhetoric, the first basis of persuasive speech is the ability of the audience to sense in the speaker the integrity of the speaker. And Lincoln, who had demonstrated this at Cooper Union in the winter of 1860, was becoming known as this person of great integrity. His personality, compared to Seward or compared to Chase, was compelling. His audience might have thought, “Yes, we don’t know as much about him. Yes, maybe we’re taking a greater risk because he has less experience, but here’s a man of integrity.”

Lincoln the politician

Q: Do you think there was any sense in which Lincoln appeared to be more like America, perhaps, than some of the smoother, more accomplished candidates? I mean, was he one of the people?

A: Well, I think Lincoln’s campaign operatives did promote his story, the log-cabin story, the rail-splitter story, so to speak. Lincoln didn’t sense it at the time, but there had been a meeting, about nine months before the convention of representatives of all the leading candidates to decide where the convention should be held. And obviously, every one of these people wanted the convention held in their home city: New York City for Seward or Cleveland for Chase. Well, Lincoln didn’t really get it, but his representative did, and so when the convention was held in Chicago, that was a huge boon to Lincoln.

On the day of the voting, his operatives — he didn’t know this, either — had done a real bait and switch. They had printed extra tickets to the convention center, called the Wigwam, and when the delegates from New York and Ohio arrived, they found all the people from Illinois sitting in their seats. And then they had taken the key Seward states and they had put the people for the states with the tickets were on one side of the Wigwam and on the other side they couldn’t communicate with each other.

So the fact that it was in Chicago helped him. If it had been held in Cleveland or New York, it would have been more difficult for Lincoln to organize his forces because as people arrived in Chicago, the delegates said, “Wow, this Abraham Lincoln, he is really popular.” Well, Chicago was for Lincoln.

Q: I have something of a personal interest in Lincoln myself and decided to write (a novel) about him. As I was doing my research, I was struck by how Lincoln seemed almost cavalier about his personal safety. One time, I forget the exact circumstances, he indicated that he did not want to appear imperial in any way by arriving in a coach with six white horses. That really weighed on him; he didn’t want that kind of separation between him and everybody else. His wife worried about his safety far more than he seemed to. He’d take rides through Washington late at night, and was shot at at least once. Is this any way for a president to act?

A: First of all, it should be remembered that there had been no assassinations of a president before. But having said that, some people say — I don’t always like this word — but Lincoln was fatalistic. I don’t like it because that is the wrong sense of his religious belief, but he was fatalistic in terms of his own life. And so, yes, his wife worried about him. Without Lincoln’s knowledge, his lawyer friend from Illinois, Ward Hill Lamon, actually slept in front of his bedroom door the night he had been re-elected and wrote Lincoln a letter saying, “Don’t you realize that there are many, many people out there who would like to take your life?”

They didn’t really have a strong secret service or all the protections that we now just assume go with the presidency. So it’s somewhat hard to understand, and Lincoln either failed to grasp this or — I don’t know if cavalier is the right word — but yes, he did not take the measures that you might have expected.

Q: Well, I was impressed just how he didn’t want to put up any walls between himself and people.

A: Yes, that’s a good point and this was a very — he drove his secretaries crazy by always being available to people. He called his times with the ordinary person his “public opinion baths,” and any one of these people, in a sense, could have walked in with a knife or a gun or something like that.

The military loved it because he took a lot of time to be with the troops, not in a regal way but just to hobnob with them, just to walk into the hospital tents to be with them. The troops came to call him “Father Abraham,” and this was a term not simply of appreciation. This was a term of affection, and as people came to know who this man was, they really loved him.

Q: Would you say that a transformational leader is someone who is approachable, who has an interest in public opinion and keeping a finger on the pulse of things rather than taking everybody else’s word for it?

A: I think this is true. And if you look at some of the presidents who had preceded Lincoln who were somewhat unknown as he was, this is, again, what separated Lincoln. As the word got out that Lincoln would see people, he would see the wives of Confederate prisoners. He would see the mothers or wives of people who the generals had ordered to be executed. Lincoln hated what he called “Butcher’s Day,” which was usually Friday, when a sentry who had fallen asleep or a man who had refused to fight was sent to him to be executed. And again and again and again Lincoln would pardon these people because Lincoln understood. He wrote to one of the generals, “I think this man will do better above ground than below ground.” And that man went on to win the Congressional Medal of Honor.

So Lincoln made himself accessible to people and the word got out how accessible he was. Frederick Douglass, the greatest African-American of the 19th century, campaigned to get more black troops into the military, and when he discovered that the troops were not being treated fairly and were being paid unequally, he was encouraged to go see Lincoln. He wasn’t very enthusiastic or optimistic that Lincoln would see him but when he arrived, why, five minutes after he presented his card to Lincoln’s secretary, the door opened, and Lincoln stood up to greet him. This is another example of Lincoln’s making himself accessible and available to people.

Turning a rivalry into a friendship

Q: I was struck by the point you made about how he had a knack for making allies out of competitors and rivals. How did this aspect of his personality affect his presidency?

A: Well, I think a great example of this starts with Seward, who was his chief competitor, who he invited to become secretary of state. And when he was asked, “Why would you invite Seward and Chase and Bates into your cabinet?” “Well,” he said, “these are the most able men in America. Why wouldn’t I want them in my cabinet?”

But Seward, as you can imagine, had feelings of envy, so after the first few weeks, the newspapers, even The New York Times, which at that time was a Republican newspaper, were saying, “We have no policy. We have no policy. What is Lincoln doing? Why don’t we have a policy?”

So Seward, at the end of March, wrote Lincoln a letter and said, “We have no policy. It appears everybody’s saying that, and I would like, as secretary of state, to begin to take the lead on formulating a policy.” The secretary of state did that in the 19th century. There were some very powerful secretaries of state who in many ways were more able than the presidents they were serving.

So Lincoln received this letter and he said to Seward, “Well, if it’s all right with you, I am the president of the United States, and I think I will take the lead in formulating the policy.” Well one month later, Seward wrote to his wife, who stayed in their family home in Auburn, New York, and he said to her, “Lincoln is the best of all of us.”

People were fond of recalling that Seward had a house on Lafayette Square just across from the White House, and Lincoln loved to walk over to Seward’s home in the evening. They fell into a great friendship, but you couldn’t have seen two more opposite people. Seward smoked 15 or 20 cigars a day. Lincoln never smoked. Seward had this huge liquor collection in his house. Lincoln didn’t drink. Seward was fond of telling all these off-color stories and using language, just always swearing and stuff. Lincoln didn’t swear.

So they were very different, but they found friendship. They could laugh together, and Lincoln really grew to appreciate Seward as a very, very able secretary of state. So here, he took his chief rival and turned him into a friend.

I don’t know that he ever turned Salmon Chase into a friend. Chase was always undercutting Lincoln, demeaning him, criticizing him behind his back, and wanting to run against Lincoln in 1864. Chase was secretary of the treasury. Well, people said to Lincoln, “Do you realize that Chase is cutting you down all the time in public?” He said, “That’s OK. I understand Chase is doing that. But,” he said, “Chase is also doing a very good job as secretary of the treasury.”

Well, when Chase got angry, he would resign. So he resigned once; Lincoln refused to accept his resignation, then he resigned a second time. Lincoln refused to accept his resignation. He resigned a third time. This time, to Chase’s surprise, Lincoln accepted it.

Then in 1864, the chief justice of the United States, Roger Taney, died, and the question was who would be his replacement? Lincoln selected Chase, and people said, “How could you do that? This man has been undercutting you for four years?”

He said, “I know that, but Chase is the most able person, and we now have in place the Emancipation Proclamation, and we don’t know whether this can last beyond this presidency. It could be overturned by the next Congress. It could be overturned by a new president. It might be overturned by the Supreme Court. Chase is a staunch anti-slavery man. I want him sitting as a Supreme Court justice. I hope there will be an amendment outlawing slavery, and if there is, it’ll be very important to have Chase as the head of the Supreme Court.”

So what does this say about Lincoln? He didn’t allow the pettiness that somebody was critical of him to keep him from recognizing that Chase was the best man to be the U.S. chief justice.

Q: In terms of Lincoln’s own family life, I know that the Lincoln boys, when they were in the White House, were often considered to be undisciplined little terrors, at least a couple of them.

But Lincoln’s affection for them as a father was great. How do you view a national leader who, on the public stage, worked through some very thorny issues trying to put a fractured nation back together, and yet with his own children, he sort of gave an exasperated, good-natured shake of the head and tolerated their exuberance?

A: Well, one way to look at that is to look back at Lincoln’s own parenting by his father and mother. He felt his father never really either understood him or affirmed him. So that might have affected the fact that Lincoln very much wanted to affirm these boys.

I suspect that Mary was a disciplinarian. She probably was critical of Lincoln for not being one. But I guess Lincoln decided that if he was going to err, he was going to err on the side of affirmation. He loved these boys. He wanted them to know he loved them.

When Willie died at age 11 in February of 1862, he was heartbroken. But the person most heartbroken, in many ways, was Tad, the younger brother. And so Tad began to be inseparable from his father. Late at night he would just lie down under the desk at his father’s feet and fall asleep, until Abraham would finally go to bed at 10 or 11 at night, and Abraham would just pick him up and take him to bed. He knew that this boy needed this kind of love and affection, and Mary was so terribly distraught over the death of Willie, he needed to step forward with an almost maternal affection for Tad.

Flaws in transformation leaders

Q: We touched a little bit ago on some of the vitriol in the editorial cartoons of the day. People were pointing out Lincoln’s flaws, or what they thought were his flaws, left and right. Do you think he possessed any particular flaws?

A: In my biography, I pointed out that as a young man, his humor could hurt and his satire could bite. He could be very withering in his criticism of people. His decision, also, to be drawn into almost fighting a duel, was a foolish decision about which he was terribly embarrassed. And he asked people not to speak about it again, how he could have almost fought that duel.

Then, I think if there is a flaw in his presidency, it is Lincoln’s sense of respect and deference. The question I’ve been asked the most is: Why didn’t he fire McClellan earlier? I think he respected McClellan, even though McClellan was so young, in his 30s. He understood what a lot of detractors didn’t understand, that McClellan was quite popular with the troops.

Perhaps Lincoln’s deference and respect didn’t allow him to make some decisions to terminate some of his commanders as soon as he should have. The timing of making decisions is important to being a decisive leader. I think Lincoln often was a decisive leader, but if you want to criticize him, you could say that sometimes he waited too long to make these decisions.

Q: Do you think a transformational leader knows his shortcomings and admits to them?

A: I do. I really think that part of it is that a person is aware of his shortcomings and is willing to admit to others his or her shortcomings. So I think Lincoln probably was aware that if he erred, it was on the side of deference and respect and timing. So maybe he could have come forward with the Emancipation Proclamation six months earlier but as he said to Sumner, “You and I have the same idea. We have a different clock.”

Q: A confident transformational leader probably doesn’t worry too much about polishing his own image.

A: No, no. In fact, there’s a funny story where one Sunday afternoon, Lincoln, an inveterate reader of newspapers, was reading one newspaper after another after another after another, and he finally looked up at his secretary, John Hay, and said, “Lincoln, you really are a dog.” Because all these editorials were criticizing him. And he laughed when he said that.

Q: Some people, including you, have noted some of Lincoln’s reluctance to stand for office or to jump into the fray. I don’t know how much of that’s humility and how much of that was just apprehension. But could you talk about that? Was there any reluctance on his part either to stand for president or to play the role of emancipator?

A: This is hard to know exactly. I think he felt he knew the cost of being an elected official. He had a genuine, honest sense of reluctance because there were others more seasoned, perhaps more experienced than he. But once he made the decision, then he was willing to go forward, and he was the first person reelected since Andrew Jackson 32 years earlier, in a nation only 76 years old. So once he made that decision and that commitment, then he was confident in himself and his ability to lead.

Q: So what might we say about transformational leaders in terms of factors that help them overcome fear or reluctance?

A: Well, I think in some ways a transformational leader is also sensitive to the feelings of others. There was a young newspaper reporter in Illinois who said, “I don’t know that Lincoln fully realizes how able he is and how influential he is.” And so in a certain sense, the leader is dependent upon those around him who either affirm or do not affirm, and Lincoln did have quite a collection of people, with whom he had cultivated relationships on the legal circuit, these lawyers and, in the case of David Davis, judge in Illinois became some of the key people in his campaign when he ran for president. And these were people who had watched Lincoln over the years, who had come to really believe in him, and they became his chief supporters in saying, “Yes, you can. You can do this. You’re the best person out there.”

A "tremendous listener"

Q: You touched on Lincoln’s compassion for battle losses on both sides of the war, and you had mentioned his great capacity to listen to others and the critical empathy with which he would greet their plight. Can you talk about that his ability to listen a little bit in terms of transformational leadership?

A: I think that’s probably the missing ingredient in today’s transformational leadership. We tend to focus on Lincoln the great speaker, maybe our greatest, most eloquent president, but Lincoln was a tremendous listener. It really bothered me to watch the various talk shows during the election. CNN would often have seven to ten talking heads and it was like a bunch of children in the third grade sticking up their hands and saying, “My turn, my turn, my turn.” You could just sense they weren’t listening to each other, but they wanted to get their word in.

Lincoln was a wonderful listener. He would often arrive at speaking engagements early, and he would talk with people in the crowd. He came to Gettysburg early because he wanted to travel out on the battlefield. He wanted to talk to some of the wives and mothers and hear about what they were feeling.

During the Lincoln-Douglas debates, they were often interrupted right in the middle of speaking by comments and questions. You had to be fast on your feet. I think today’s campaigns are often so managed that I’m not sure that people are really listening. And I think the modern forms of both radio and television really work against listening. I remember a question that was asked of Sarah Palin during a debate, and she said, “Well, I don’t intend to answer that question.” And then she just went on to say what she wanted to say.

The debates are no longer debates. These people have come in on either side with the talking points they’re going to make, and no matter what the moderator asks them, they don’t listen to that question. They just seize it as an opportunity to say what they want to say. We’ve lost the capacity to listen, and I think one of the great qualities of Lincoln was his capacity to listen to people.

Lincoln, the Confederacy, and reconciliation

Q: How do you think Lincoln’s ability to listen might have affected how he treated the Confederacy after the war concluded?

A: Well, I have found myself, since I was at Seattle Pacific, speaking in the South again, and I was in Montgomery, Alabama, and I wondered, “Well now, how will I be received?” I was speaking at a wonderful Methodist college and wondering if there would be some of the rebels or the Sons of the Confederacy coming to my lecture. They didn’t, but I really wanted to say what Lincoln said: “If I lived in the South, I would think as they did. I would act as they would. I would have no idea how to get rid of slavery.”

So Lincoln, again, had this wonderful capacity to put himself in the shoes of others, and that’s a rare gift and that’s part of being a transformational leader, to really try to put yourself in the shoes of other people.

Q: It is. Of course, his attitude and the way he modeled treating those who lost the war probably staved off perhaps even more revengeful kinds of acts.

A: It did, and I think this was obviously translated through Ulysses S. Grant in the wonderful peace that he offered at Appomattox, where he told the defeated soldiers that they could take their horses, they could return home. He instructed the Union troops there would be no cheering, no derision. There would be only respect. And he told Robert E. Lee, “We’re all now part of the same nation.”

If Lincoln had lived — this is a question I’m often asked — it would have been very difficult, but I think he would have been so much better able to combine strength and forgiveness that we might have had quite a different nation. I think the South felt for at least 100 years, if not more, that they had been poorly treated after the war.

We saw what happened in World War I. We forget this story, but the Germans were so badly treated by the French that they harbored a deep resentment that could then produce a Hitler to come back and restate German solidarity. But we learned from that in the way that we treated the Germans and the Japanese after World War II. There was a great deal of obvious bitterness towards the Nazis and towards the Japanese but we decided not to push them down but to lift them up. And now Germany and Japan are two of our chief allies.

Q: I’m always struck, how at various points in his presidency, Lincoln called the nation to repentance and reliance on the Almighty. There’s a line here in the Thanksgiving Proclamation that says – well, I better read the whole thing:

“To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever watchful providence of almighty God.”

So he was even speaking to those who ignore God much of the time. I love that about him.

A: When Lincoln quotes the Bible, for example, he’s not just quoting the Bible as literature, as so many people have assumed. He is drawing from the deepest wells of the Christian tradition. At the heart of the Christian tradition is the understanding of forgiveness, and the forgiveness is rooted in Jesus’ death on the cross. And Lincoln understood that. In a nation bitterly divided, he called for repentance, forgiveness, and ultimately for reconciliation.

Q: That’s awfully bold for a politician.

A: It’s very bold and surprising. A lot of the newspapers picked up on how surprising this was.

Judeo-Christian faith and the United States

Q: Oh, to hear that again these days. I don’t know what it’s going to take. Do you think it was a sense of him appealing to our better natures?

A: I think it was. I think he was very conscious of the whole tradition of the United States. When he said “the better angels of our nature,” he appealed to this. He obviously knew that this is a religious nation. Lots of people say, “Well, he only used the language of the people who came to hear him.” No, it’s far more than that. He appealed to the best part of the American people, which is rooted in Judeo-Christian faith, to bring this faith to the surface as the great crisis came to a close with the close of the war.

Q: Is the more effective leader the one who can convict the conscience of a people or the one who can placate the critics? There seems to be an awful lot of placating going on these days.

A: Right. And Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address is really alone among almost all inaugural speeches in the fact that he said to everyone, not just to the South but to the North, “We have a great offense,” which is what he calls American slavery. This is like the Puritans who preached Jeremiads. They were saying, “You have forgotten. You, the second, third generation, you have forgotten the faith of your founders, and God has a complaint against you.” Puritan preachers would have said, “You’ve fallen into immorality.”

Lincoln said, “God has a complaint against you, and the complaint is the offense of American slavery. And this is a moral universe, and because we’ve been at this now since the very beginning, way back to 1620, we’re going to have to pay the cost, which is the death of 620,000 soldiers, because we have afflicted the slave with the lash for all these centuries.”

Well, this was not a popular thing to say at all. Inaugural addresses are usually about self-congratulation of the candidate and self-congratulation of the people — aren’t we a wonderful nation? And Lincoln was saying that we are a wonderful nation, but we have a huge, huge hurt in our nation, and we have to face up to it.

"Uniting" around "a common cause"

Q: We talk a lot about two things in our nation these days. One is uniting, coming together around a common cause. And then at other times, we talk about American individualism and pulling ourselves up by our own bootstraps. And sometimes we respond to violence or disaster in the world one way and sometimes another. How do you think the ways in which Lincoln conducted the war demonstrate these two ideas?

A: In terms of the tension that’s always in America between individualism and community; Lincoln, in many ways, appealed to community, the common good, the union. And Alexis de Tocqueville, in his Travels in America and his book in the 1830s, Democracy in America, was the one who pointed out Americans’ individualism. De Tocqueville said it was the source of a lot of the drive and energy and success of Americans, but he looked down the road, 150 or 200 years, and said, “I could foresee a nation that by this unchecked individualism could be a nation deeply isolated, where people are isolated from each other. They’ve forgotten the common good.” And so Lincoln lifted up the common good, the idea that we all are part of this union, and I think this is the strength of what he offered.

I think right at the heart of the health care debate, if I may say so, is the question: What is the common good? I feel somewhat dispirited as I hear people appeal to what’s good for me. But how can anything be good for me if it isn’t good for all of us? That’s what Lincoln was really saying. If it’s only good for me, then that is going to divide us and isolate us. Lincoln said that the union must come together, and he was trying to hold us together, and that’s a tough thing to do in any age.

Q: And to pull it off is pretty transformational.

A: It is, and a transformational leader is able to see the common good and to get people to buy into that common good that may not necessarily be good for me but is good for all of us. I may have wonderful health care because I happen to be a person of certain economic means, but am I concerned about the 36 million or so who don’t have health care? That’s the common good.

So Lincoln is saying, well, we may have certain privileges here, but for our nation to go forward, “All men are created equal” means that slavery must end. That’s the common good.

Lincoln's most significant changes

Q: If you had to list maybe the two or three most significant changes that Lincoln brought about as an American leader, what would those be? What is his lasting influence?

A: Well, 100 years ago, when we celebrated the centennial of Lincoln’s birth, one thing would have clearly been the preservation of the union, which has sort of slipped out of the conversation today. We take it for granted, but America was an experiment, and France and England were not betting that it would last. They were almost betting on the Confederacy. So the fact that this experiment has now become this long-established democracy, that the union has persevered — we have to give Lincoln the credit.

Secondly, he was able to come forward with the Emancipation Proclamation. There is no union without liberty. It is what we, looking back, would call the second American Revolution. We had a very different nation coming out of the Civil War than we did going in.

I would argue that those two acts are remarkable and always should be esteemed and remembered, but thirdly, there are Lincoln’s words. We study many people in the university, but we repeat almost none of their words in the 21st century. We really don’t repeat the words of George Washington, although we often remember him. We read a lot of people in literature, and sometimes we might want to repeat their words or their poems, but somehow, with Lincoln, his words still seem to be worth repeating in the 21st century. They seem to have a transcendent quality.

My argument is that Lincoln is telling us words fiercely matter, that words are actually actions. And therefore we still say Lincoln’s words in the 21st century even though he wrote them in the 19th century. And that’s why I think he is a transformational leader who stands out above all of our leaders in the story of America.

Return to top

Back to Features Home

|