Teach a Girl, Teach a Community

Greg Mortenson works for

peace through education

in Central Asia

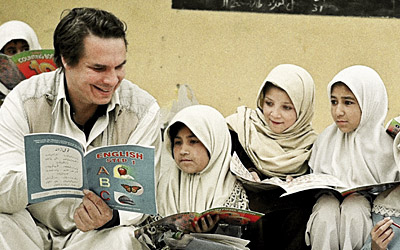

Building schools and literacy: Greg Mortenson reads with Gultori schoolchildren in Pakistan.

When Greg Mortenson sent his book Three Cups of Tea (Viking Press, 2006) — the story of his journey from mountain climber to humanitarian advocate — to his publisher, he discovered that he and his publisher differed over the book’s theme.

“I picked the title, but the publisher picked the subtitle,” he told a crowd of more than 2,000 at Seattle Pacific University’s Royal Brougham Pavilion this past December. “They said it would be ‘One Man’s Mission to Fight Terrorism One School at a Time.’”

But for Mortenson, his work building schools, especially for girls, in Afghanistan and Pakistan isn’t about fighting terrorism. It’s about promoting peace. And he wanted peace, not terrorism, in the subtitle of his book.

Mortenson, who has attempted to climb the world’s second-highest mountain and has built relationships with Afghan militia commanders, is not one to shy away from a challenge. So he made a deal with the publisher.

“If you work in Afghanistan or Pakistan for a while, you learn that you never settle a deal without driving a hard bargain on the side,” Mortenson said. So he told the publisher, “If the hardcover doesn’t do well, please change the subtitle to ‘One Man’s Mission to Promote Peace One School at a Time.’”

Mortenson got his way. And when the paperback book came out, with his subtitle, it spent more than 150 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list.

Mortenson is also author of the current New York Times best-seller Stones Into Schools: Promoting Peace With Books, Not Bombs, in Afghanistan and Pakistan (Viking Press, 2009). He is cofounder of the Central Asia Institute and Pennies For Peace. His counsel is sought by leaders around the world, including America’s highest-ranking military officials. When he isn’t helping to build schools in Afghanistan and Pakistan, he lives in Montana with his family.

The following are excerpts from

Greg Mortenson’s presentation at SPU:

Don’t Help People, Empower Them

I’m basically from Minnesota; I was born there. But when I was 3 months old, my parents went off to Tanganyika in East Africa, where they [worked] as teachers in a girls’ school.

But my father ended up deciding to start a teaching medical center called the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, and he worked very hard to get the hospital started. There were a lot

of setbacks, but one thing my father always insisted on was

having local people in charge.

Sometimes that didn’t go over very well with the Americans and Europeans; they said, “You need a qualified mzungu” — meaning a white man — “to run this hospital.” But my father insisted.

When the hospital opened up in 1971, my father got up and gave a little speech. He said, “I have a little prediction to make that in 10 years, all the department heads of the hospital will be from Tanzania.”

Well, basically, he got laid off for having the audacity to believe that the hospital could be run by Africans. We came back to the States, and unfortunately my father died from cancer in his mid-40s.

But we got the annual report 10 years later, and all the department heads were from Tanzania. And even today, 38 years later, all the department heads of the KCMC hospital are from Tanzania.

It’s a very important lesson that people can be empowered. We have to take the risk and have the confidence, and really base it, not on helping people, but empowering people.

Education

[There’s an African proverb:] “If you can educate a boy, you can educate an individual. If you can educate a girl, you can educate a community.” …

The more I do this, I’m convinced that education has to be our national and international top priority. …

There are tens of thousands of kids in West Africa who have to harvest three million tons of cocoa a year, and cocoa is very difficult. You have to hit a stick, a pod falls down, and you break it open with your fingers. Kids are most dexterous, so they can open up the cocoa pods.

In Congo, tens of thousands of kids are forced to kill at age 6, or 8, or 10, and become child soldiers. If you teach a child how to kill, their conscience won’t really develop, and they will kill with impunity — it doesn’t really register as they mature.

The next time you pick up a soccer ball, look closely, it’ll probably say “Made in Pakistan.” If you look very closely, you’ll see small, leather felt patches sewn together — it’s probably made by a child.

I’m not saying to ban chocolate or have protests against

soccer balls — but it’s important that the reason kids are being so exploited is because of the lack of opportunity and hope

for education.

I feel it’s especially important that we make a huge attempt

to help girls go to school. We can drop bombs, we can hand out condoms, we can surge troops, we can build roads, we can put in electricity, but unless girls are educated, a society will never, never change. …

Girls attend the opening of the Pushghar Village Girls School, Panjshir Valley, Afghanistan, a school that Mortenson helped to build. |

When a girl learns how to read and write, she often teaches her mother how to read and write.

Boys, we don’t seem to do that as much.

You also see people coming home from the marketplace, and they have meat or vegetables wrapped in newspaper, and then the mother very carefully unfolds the newspaper and asks her daughter to read the news to her. It’s the first time the woman can read news and understand what’s going on in the world around, become politically involved, or understand issues like exploitation of women, or even some of the successes that women are having.

Also, when someone goes on jihad — the jihad, by definition, is a struggle or quest — it could be a spiritual endeavor, or it could also be joining a militant group — they should first get permission from their mother. If they don’t, it’s very shameful.

When a woman has an education, she’s much less likely to encourage her son to get into violence or into terrorism. I’ve seen that happen in thousands of circumstances. The Taliban, their primary recruiting grounds are illiterate, impoverished society because most educated women refuse to allow their sons to join the Taliban, even sometimes at risk of their lives.

Whose Side Is God On?

You know, sometimes I hear Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, or other leaders say something like, “God is on our side.”

But you know what?

I think if God is on anybody’s side, God is on the side of the orphan, the refugee, the widow, the wounded veterans, and all those 120 million children in the world who can’t go to school.

Until every widow has hope, every orphan has love and shelter, every wounded veteran has a chance to heal, and every single one of those 120 million children in the world who can’t go to school can go to school, I don’t think that any of us here have the right to say, “God is on our side.”

The Importance of Play

We’ve had our best year ever in Afghanistan. We’ve set up about three dozen schools, and we’re going now into more volatile, remote areas, areas where the Taliban are. We were able to set

up the first girls’ high schools in five new provinces in Afghanistan. And one of them is in Uruzgan province.

This happened in a very interesting way: Last year we set a goal that maybe in 20 years, we might be able to put a girls’ high school in Uruzgan province, which is the home of Mullah Omar, the leader of the Taliban. That’s kind of our long-term goal — not short-term, long-term.

So only a few months later, we got contacted by the Shura, the elders of Uruzgan, and they said, “We want a school in

Uruzgan, a girls’ school.” So I said, “Well, why don’t you come and visit a school first, and let’s talk.” This spring they came over to Char Asiab Valley. These are black turbans, armed to the teeth. When they got to our school, they saw the giant playground, so they put down their weapons and for the next hour and a half, they went on the swings and slide and had a glorious time. Turbans flying all over the place.

After an hour and a half, I said, “You know, let’s get serious now. Let’s go see the headmaster, and [we’ve] got to look at the curriculum.”

They said, “No, no, we’re totally satisfied. We want a girls’ high school in Uruzgan province. But you must put in a playground first.” …

So we started construction six weeks ago, and of course the playground started first. And my only worry is that they’re going to use the playground, and the girls aren’t going to get to use

the playground.

But in all seriousness, I’ve talked to these men a lot, deep into the night. They had no chance to play as children. They didn’t have that joy; they were in war, they were in destruction, they were traumatized. Many of them lost their parents; they never even saw their father. When you think about it, play is really

so important.

A Legacy of Peace

I’d like to leave you with words of Martin Luther King Jr.,

who said, “Even if the world ends tomorrow, I will plant my seed today.”

I think, most of all, we have to really learn from our elders, but the real hope for peace is with our children. And we

cannot live in fear; we must live in hope. We must — we can’t exude trepidation and fear to our children; we have to give them hope.

When I look into the eyes of the children in Afghanistan or Pakistan, I see my own two children, or all the dear children here, and I think we need to do everything we can to leave our children a legacy of peace.

It doesn’t start with troop surges or computers or electricity or roads or anything else. It’s people who bring peace.

Hear the Podcast

Listen to the Seattle Public Library podcast of Greg Mortenson's presentation.

Return to top

Back to Features Home

|