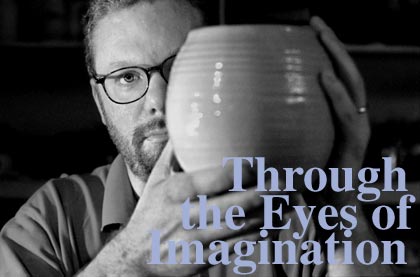

By Gregory Wolfe,

SPU Writer-in-Residence

and Editor of Image

Photos by Jimi Lott

![]()

![]()

When Gregory Wolfe was young, it wasn't hard for his

family

members to teach him to respect art and the imagination. After all, many of

them

were artists and writers themselves.

"My grandfather trained at the Royal Scottish Academy of Art in Edinburgh,"

says

Wolfe. "I grew up with his paintings on the wall. We lived in New York City,

and

my mother often took me to the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim

Museum. My dad, a writer, was always working with words and publishing his

work."

Now combining those early influences, Wolfe works as Seattle Pacific

University's

first writer-in-residence and edits Image: A Journal of the Arts and

Religion,

a leading literary quarterly. "My wife, Suzanne, and I founded Image

because we felt that too many Christians had become alienated from

contemporary

culture," says Wolfe. "In becoming part of SPU, we wanted to help deepen and

extend the University's dialogue on the role of the imagination in the

Christian

life."

Among Wolfe's books are Malcolm Muggeridge: A Biography

(Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1997) and

Sacred Passion: The Art of William Schickel

(University of Notre Dame Press, 1998). His most recent book, co-authored

with

Suzanne and inspired by their four children, is Circle of Grace: Praying With — and for —

Your Children

(Ballantine, 2000). He received his M.A. in English literature from Oxford

University.

Sacred Passion: The Art of William Schickel

(University of Notre Dame Press, 1998). His most recent book, co-authored

with

Suzanne and inspired by their four children, is Circle of Grace: Praying With — and for —

Your Children

(Ballantine, 2000). He received his M.A. in English literature from Oxford

University.

|

"[Jesus] spit on the ground, made

some mud with the saliva,

and put it on the man's eyes. 'Go,' he told him, 'wash in the pool of

Siloam.' ... So the man went and washed, and came home seeing." John 9:6,7 In this Gospel passage, Jesus heals the blind man in a way that stands out from many other accounts of Jesus' healing. He mixes his own spit with dirt to make a clay poultice for the blind man's eyes. I don't think it's stretching things too far to see this as a metaphor for art. Art, after all, is a mixing of something that emerges from deep in the artist using the materials of the world around us — materials like words, pigment, clay. From that mixture comes something new, something that, when it is well-made, can help to heal our blindness. Nor is it a stretch to say that Jesus is the consummate artist, the model for all artists. If you go back to the magnificent beginning of John's gospel, in which Christ is spoken of as the Logos, the creative Word, you will read John's claim that "without him was not anything made that was made." Christ the Word is the agent of creation, the model for artists and writers. His preferred form of teaching, after all, was that complex literary form known as the parable. |

||

|

"God's revelation is mediated not through a

set of logical

propositions but through the artistry of language."

The parables are brilliant verbal constructs, traps for the unwary. They begin with common things: workers, masters, mustard seeds. But each parable moves in a startling way from the familiar to the unfamiliar. Workers who labor for an hour are paid the same as those who've worked all day; a despised outsider shows more compassion for a mugging victim than do members of God's chosen people. The parables catch us out, force us to admit our petty, unimaginative ways of thinking. They cannot be absorbed passively; we must participate in them. Our response literally completes the story by making it our story. If we stop to think about it for a moment, we will realize that the entire Bible is full of stories, poetry, prophetic vision. While it is wrong to consider the Word of God to be "merely literature," it is never less than literature. God's revelation is mediated not through a set of logical propositions but through the artistry of language. But in the history of Western civilization, the imagination — which lies at the heart of art — has often been given short shrift. There has been a tendency in the West to speak of faith and reason as the two great faculties of the human soul. The imagination has often played the role of Cinderella, taken for granted, or at least left implicit, not fully celebrated. "In a more complete picture of the human soul, imagination shines forth in a trinitarian relationship with faith and reason." A closer inspection both of the Bible and of the greatest theologians — from Gregory of Nyssa to Dietrich Bonhoeffer — demonstrates that the imagination is an indispensable aspect of both faith and reason. Imagination is like faith, in that it dares to see meaning that is buried beneath the surface of things. But the imagination depends on reason, too. Without reason, art would not achieve complexity of form or vision. In a more complete picture of the human soul, imagination shines forth in a trinitarian relationship with faith and reason. We might say that art is incarnational: a union of form and content, flesh and spirit. Author Flannery O'Connor speaks of the need to bring mystery and fact into harmony. Those who try to enshrine the mystery without the fact become vague and abstract. Those who choose fact without mystery are left with an inanimate lump of clay. So it is vital that we see art not just as fancy decoration around what is otherwise a set of rational propositions. To think that way is to reduce art to nothing but sugar coating around the pill of truth. No, many of the great Christian thinkers have held that art is its own way of knowing the world. To do without it is to diminish our awareness of the world, to become literalists who can't see the wood for the trees, to allow blindness to gradually cloud our sight. "As we enter the imaginative world, we become vulnerable. But it is precisely in that vulnerability that we become open to grace, to the touch that can clear our vision." Yet throughout history, there have been Christians who have feared the imagination. In the name of holiness, images have been smashed, canvases shredded, books burned. True, the same impulse that might create an icon could, in a sinful mind and heart, fabricate an idol. But as the medievals used to say, the abuse of a thing does not nullify its proper use. The imagination stirs fear because it possesses a visceral power. It can lead us to places we can't foresee or control. And yet that is precisely what Jesus does, to our inestimable benefit, in his parables. Those stories were the cause of scandal. They undermined the complacency of many in Jesus' audience. Imagination involves risk, but without risk our spiritual lives become hollow and inert. An encounter with a work of art involves something akin to surrender. As we enter the imaginative world wrought by another, we become vulnerable. But it is precisely in that vulnerability that we become open to grace, to the touch that can clear our vision.

|

|

|

|

Through the imagination we enact the fundamental principle that Jesus came to teach: we must learn to see through the eyes of others. In allowing ourselves to be transported into the experience of others, art takes us out of ourselves, teaches us compassion. And because compassion means "suffering with," the imagination has to take into account the whole of reality, including the existence of evil, death and human folly. That is why art is not, and should not be, a matter of mere "uplift," to quote O'Connor again. To treat art as uplift is to reduce it to mere entertainment. While it can serve that purpose, that is not its highest end. Great art makes demands; we have to work to grapple with its picture of reality. In that sense, the greatest art is like the parables of Christ: It demands our inner response, our completion of the story. "There is, in fact, a true Renaissance of art and literature going on now, one that incarnates the Judeo-Christian tradition of faith." Too many Christians have essentially despaired of the faith's ability to renew culture. That despair is ill-founded. There is, in fact, a true Renaissance of art and literature going on now, one that incarnates the Judeo-Christian tradition of faith. In the face of modernity, many Christians have preferred to retreat into a subculture, but to do this is to retreat from the Christian call to be stewards. The Romantic image of the artist as being aloof from the community has done terrible damage in our society. Art must exist in a dialogue with the community, with the Church. Art can perplex and occasionally scandalize, but there are risks in any form of expression. May we all draw closer to God through his precious gift of imagination, the gift that, at its best, helps us to capture glimpses of mystery through fact. May works of art — those we make and those we encounter — become vessels of grace, ways in which our blindness is healed. |

||

![]()

| Please

read our

disclaimer.

Send any questions, comments or correspondence about Response to

jgilnett@spu.edu or call 206-281-2051. Copyright © 2001 University Communications, Seattle Pacific University.

Seattle Pacific University |