What Brain Research Does (and Doesn’t ) Tell Us About Learning

THERE IS LITTLE AGREEMENT about how

the human brain functions. In fact, says brain

researcher Michael Gazzaniga, “If we ever

learned how the brain learns to pick up a

pencil, it would represent a major achievement.”

Thus, while my role in Seattle Pacific

University’s Brain Center for Applied Learning

Research is to explore the connections

between brain science and the world of education,

there is a challenge. I reluctantly

believe that brain science has very little to

say at this time to the world of education.

(Click image to enlarge.)

|

|

Given this perspective, is there any point

to a Brain Center for Applied Learning

Research? Although we don’t know much

about how the brain actually learns, I do

believe robust theoretical common ground

exists between the investigative brain sciences (especially the so-called cognitive

neurosciences) and the world of education

— as long as there is also room for a powerful

sense of boundaries.

Even if the brain data were mature, most

brain scientists have never taught 30 fourth

graders in a typical American classroom, half

of whose parents are getting a divorce, and

a quarter of whom are on some form of psychoactive

medication. Most educators do not

know how to run noninvasive imaging equipment,

or navigate their way through the subtleties

of brain development at the cellular

level. Yet, if we assume that education is at

its fundamentals about brain development,

these differing skill sets are hardly incompatible.

Rather, they are complementary — and,

from a research point of view, especially if

you are interested in end-use results, could

create a potent scientific force.

This, of course, suggests that brain professionals

and education professionals

conduct research together. And that is the

whole point of The Brain Center at SPU:

to describe a slice of biology where such

collaborative research projects might yield

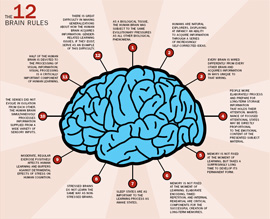

prescriptive insights. Altogether, I have identified

12 such slices, which I sometimes

refer to as “brain rules.” These simply

denote basic things we know about the brain

that could form the nucleus of research projects,

which one day might be capable of

improving American education — if brain

scientists and education scientists choose

to integrate their worlds.

By John Medina

Director of the

Seattle Pacific

university Brain

Center for Applied

Learning Research

Back to the top

Back to Home |