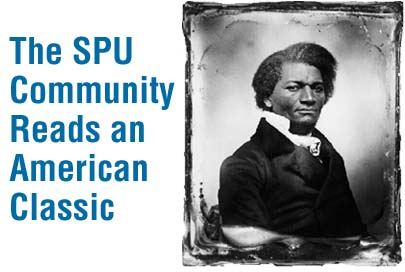

The powerful autobiography of a 19th-century former slave and abolitionist is generating campus-wide discussion about education, personal identity and authentic faith at Seattle Pacific University.

The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is not only assigned reading for freshmen entering SPU's new "Common Curriculum" this fall, but copies of the book were also given to faculty, staff, administrators, trustees and returning student leaders. Prior to the opening of school, the annual Faculty Retreat focused on the themes of the Narrative, as did a staff workshop and student leadership conference. With Autumn Quarter underway, the discussion continues in freshman classes and in several all-campus events, including a special presentation by National Book Award Winner Charles Johnson.

Response extends this exploration of a classic American text to the broader SPU community with an essay by Professor of English Susan VanZanten Gallagher. For readers interested in receiving a free copy of the Narrative, either call 206/281-2051; send an email to response@spu.edu; or write Response, Office of University Communications, Seattle Pacific University, 3307 Third Avenue West, Seattle, Washington 98119.

Professor of English

Photos by James Prichard

"We were all ranked together at the valuation. Men and women, old and young, married and single, were ranked with horses, sheep, and swine. There were horses and men, cattle and women, pigs and children, all holding the same rank in the scale of being, and were all subjected to the same narrow examination. Silvery-headed age and sprightly youth, maids and matrons, had to undergo the same indelicate inspection. At this moment, I saw more clearly than ever the brutalizing effects of slavery upon both slave and slaveholder."

In the summer of 1841, a young, handsome, unknown black man took the stage at an abolitionist convention in Nantucket to deliver the most stirring and articulate denunciation of slavery heard that day. After the twenty-something Frederick Douglass took his seat, the fiery evangelical abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison rose and declared "that Patrick Henry, of revolutionary fame, never made a speech more eloquent in the cause of liberty." A star had been born.

For the next two years, Douglass traveled through New England, telling his story to rapt audiences. His name was a pseudonym, for as a fugitive slave he was in danger of being sent back to the South.

Many did not believe that a former slave could be an effective speaker, and Douglass was advised to sprinkle some plantation phrases into his speeches to appear more authentic. With Douglass' credibility under attack, the leadership of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society asked him to write his autobiography, including verifiable names and events.

Published in the spring of 1845, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass immediately became a best-seller. Douglass, his true identity revealed by the details in the book, was forced to flee to England, where he lectured for two years until friends raised seven hundred dollars to purchase his legal freedom.

![]()

The "Most Superbly Crafted" Slave Narrative

Douglass' Narrative was not the first account written by a former slave; between 1820 and 1860, hundreds of slave narratives appeared. But Douglass' story stands out, noted African-American critic Houston A. Baker says, as "the most representative and superbly crafted" of these narratives.

Some literary scholars have argued that the slave narrative is the first truly American literary genre, since the novels, poems and more traditional autobiographies written by earlier authors followed British literary models. Douglass' superb rendition of the slave narrative influenced the continuing development of American fiction, with writers as diverse as Harriet Beecher Stowe (Uncle Tom's Cabin) and Toni Morrison (Beloved) following in his lead.

As a genre, the slave narrative most obviously serves to provide a testimony, a moral witness against the outrages of slavery. Dispelling many prevalent northern myths, Douglass chronicles the deliberate dehumanization caused by the slave system: slaves lack adequate food, clothing and shelter; families are systematically destroyed; male and female slaves are brutally whipped and sometimes killed; African women are used as sexual objects by white masters.

The Narrative opens traditionally -- "I was born in Tuckahoe" -- but immediately highlights the differences in a slave's life: "I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it. By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs. . . . A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood."

As in this passage, throughout the narrative Douglass moves between the personal and the general, between facts and emotions. Consequently his story goes "right to the hearts of men," as one 19th-century reader remarked.

Douglass himself points to the powerful moral persuasiveness of narrative art when he comments on the effects of hearing enslaved Africans sing. The "rude and apparently incoherent songs . . . breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains."

He concludes, "I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do."

![]()

"Do You See What I Made of My Life?"

As a testimony, the Narrative's primary audience was white northerners. Few slaves would have read the book, yet Douglass became, if only by reputation, an admirable example for many blacks.

Many different readers have been inspired by his exemplary story. "Do you see what I made of my life?" Douglass implies, "What can you make of yours?" The Narrative thus participates in the popular American tradition of the self-help book that stretches back to Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography. Despite legal prohibitions against educating slaves, Douglass teaches himself to read and write with cunning determination, employing white street urchins as unwitting tutors and surreptitiously using his young master's copybooks. His reading helps him to recognize the injustice of his own enslaved state and inspires his rebellion. He teaches his fellow slaves in a secret school and leads one failed escape attempt before finally reaching the North. To other former slaves who had succeeded in gaining freedom, Douglass was a powerful role model.

Besides providing a testimony and an example, Douglass' Narrative embodies his claim for an identity as a human being. Enlightenment philosophers had taught that one's humanity lay in one's rationality. Those without reason -- so-called savages or barbarian races -- could not write, or produce art for that matter. The laws against teaching slaves to read or write thus served to re-enforce Africans' position as chattel rather than people.

The very existence of the Narrative, then, avows, "I am a human being!" Further supporting this implicit argument is Douglass' eloquent style -- peppered with biblical and classical references, and moving effectively between political and sentimental rhetoric.

The Narrative forcefully demonstrates that the brutal state of many enslaved Africans was not natural, but rather was socially constructed through the institution of slavery. The details supplied by Douglass spell out the deliberate ways in which Africans were dehumanized. Treated as animals, many became animal-like in their demeanor, action and thought. Once again, Douglass' own life vividly illustrates this process.

![]()

"It Was a Glorious Resurrection"

The turning point of Douglass' story occurs not when he achieves physical freedom by escaping to the North, but when he achieves psychological freedom by defying the famed "nigger-breaker" Covey (who is also a Methodist class leader). After six months of brutal treatment by Covey, who is repeatedly described with devil imagery, Douglass reports, "I was broken in body, soul, and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!"

In an attempt to ease his oppression, Douglass appeals both to authority (complaining to his master) and to superstition (carrying a root that will supposedly protect him), but it is only when he impulsively stands up for himself physically and verbally that he achieves a kind of freedom. After a two-hour battle, Covey slinks off and never again strikes Douglass.

"I felt as I never felt before," Douglass rejoices. "It was a glorious resurrection, from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom. My long-crushed freedom rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place; and I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact."

This language of Christian redemption follows in the tradition of the Puritan autobiography in which the turning point occurs when Satan is defeated and the writer achieves salvation. Both psychologically and spiritually, Douglass has been transformed, "made a man," as he describes it.

For Douglass, being a man includes embracing the Christian faith, and his use of Christian language is not just for rhetorical effect. His story documents the greater cruelty of pious Christian (as opposed to non-religious) slaveholders and acknowledges the biblical arguments used to support slavery, yet Douglass miraculously is still able to distinguish what he calls "the Christianity of Christ" as opposed to "the Christianity of this land."

Following the Civil War, Douglass continued a distinguished career as a writer, newspaper editor, and civil servant. One of the most important African-American leaders of the century, he updated his original story in My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881). The Narrative, however, remains his most moving and inspiring work.

In writing the story of "how he became a man," Douglass created and publicly claimed a personal self. In asserting his humanity, he provides us with both an admirable example of achievement as well as a powerful testament against prejudice.

![]()

Susan VanZanten Gallagher received a Pew Evangelical Scholar's Fellowship in 1996 that allowed her to travel to South Africa to research her book Confession in South African Literature. As a scholar, she has welcomed opportunities to broaden the traditional literary canon. "There's a movement toward reading other literature in addition to British, European and American works, and this has opened up our thinking about what literature is," she says. Gallagher's own journey into a career as a literature professor began in the 1970s when she earned a bachelor's degree in English at Westmont College. She went on to receive a master's degree from Emory University in 1981 and a Ph.D. from Emory in 1982. She has taught at SPU since 1993.

![]()

| Please read our

disclaimer.

Send any questions, comments or correspondence about Response to

jgilnett@spu.edu or call 206-281-2051. Copyright © 1999 University Communications,Seattle Pacific University.

Seattle Pacific University |