SPU >> Response >> Exclusives

Commander in Chief Lincoln’s Constitution

and the Case for Presidential Power

Constitution Day 2010

Posted September 17, 2010

By William Woodward, Professor of History

It was the Fourth of July, and the nation was at war.

With itself.

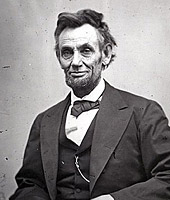

The recently inaugurated president, renowned for compelling oratory, now had to deliver a fateful message as commander in chief. He faced a special session of a Congress missing the delegates from the 11 self-styled “Confederate States of America.” Two-and-a-half months earlier the first shots of the American Civil War had been fired. Since then, President Abraham Lincoln had wielded unprecedented (to some alarming) executive power, unconstrained by an absent Congress or a helpless Supreme Court.

Could he justify what he had done? Could he ask the legislators for even more authority to suppress the rebellion?

Could the prairie politician reason his way into forbidden terrain — to stretch the United States Constitution far enough that he might save it at its moment of greatest peril?

How would lawyer Lincoln read his country’s highest law? How would President Lincoln lead a fractured people? How would Commander in Chief Lincoln define and deploy his wartime powers?

Legal scholar Daniel Farber rightly asserts that the Civil War “put the Constitution to its greatest test” because it forced the issue of “whether the Constitution” was “authoritative” — that is, conferring enough power for its own survival, or “merely a forum for negotiating between” autonomous states.

Lincoln began his message almost whimsically: “Your attention is not called to any ordinary subject of legislation.” Rather, a movement “to sever the Federal Union” is at hand. And this momentous crisis raises

the question whether a constitutional republic or democracy — a government of the people by the same people — can or cannot maintain its territorial integrity against its own domestic foes.

Then, alluding to the extraordinary powers he had already invoked, and the criticisms, even from Northerners, leveled at his actions, Lincoln asked a fateful question:

Is there in all republics this inherent and fateful weakness? Must a government, of necessity, be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?

The question reverberates to our own day.

Perhaps, then, it would be well, on this Constitution Day 2010, when the role and reach of the presidential office remains contested, to discern Lincoln’s views on the charter he had sworn to preserve, protect, and defend — and how he translated those views into decisive action.

A continuing saga ...

This essay renews my analysis of Abraham Lincoln’s crucial influence on American constitutional government, a contribution unmatched by any president, except Washington, before or since. Indeed Lincoln, in many important respects, made the Constitution what it is today. In his moral and legal arguments against slavery, Lincoln the lawyer crafted a view of the Constitution that both recovered the original intent of the Framers and created a new constitutionally grounded vision of equality, opportunity and justice — for America and for all humankind. This I showed in a 2008 Constitution Day essay. Then, last September, I dissected the case that Lincoln built, as president-elect, against the theory of secession and in favor of America as one nation indivisible.

But Lincoln needed to win that case on the battlefield; to do so, he assumed a more hands-on role as commander in chief than any other American president. That legacy is the focus of this third study.

It remains timely to focus on Lincoln. The year 2008 marked the 150th anniversary of the legendary Lincoln-Douglas debates, and 2009 is the bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth. This year is the 150th since his election as president, and next year begins the sesquicentennial commemoration of the ghastly Civil War over which he presided. His exercise of presidential power raises questions that still divide us; to navigate these contemporary issues we must not only learn from his actions but also grasp his rationale.

And recognize his unique circumstance. Farber wryly observes that Lincoln’s efforts to preserve a system grounded in “the rule of law” under a foundational national charter put “theory and practice in terrible tension.” Hence the “great question during the war was whether the rule of law could survive the effort to defend it.”

Lincoln revered the rule of law. Two commitments anchored this instinct. First, he genuinely embraced the idea of equality — of rights and therefore of opportunity — as proclaimed in Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. Thus anyone — not least the gangly son of a hardscrabble pioneer farmer from Kentucky — deserved a chance to rise, yes, to the highest office in the land.

Second, and in consequence, the twofold task of representative government was to protect basic rights and foster economic opportunities. Lincoln accepted positive government action to enhance opportunity. Fund roads and canals. Charter a national bank to control national finance. Slap a tariff on imports to insulate American entrepreneurs. Protect patent-holders. Offer emigrants to the West a chance to get their own land. Oppose slave labor, or at least its expansion.

Lincoln thus came to the presidency fully prepared to exercise power on behalf of economic and moral improvement. At first, that meant promoting economic development while confining slavery. Then, with Southern secession, saving the Union became his focus, managing the war while cracking down on antiwar critics. Eventually, ending slavery — first on rebel ground, then nationwide — became his purpose.

But he was the party’s leader, not its lackey. In times of emergency, as constitutional historian Herman Belz puts it, Lincoln held that “not only is decisive action by a single individual to be risked, it is required.” Further, as he asserted in his message to Congress, “I think the man whom, for the time, the people have, under the constitution, made the commander-in-chief, of their Army and Navy, is the man who holds the power . . . .”

That assertion appalled many Americans: charges of “dictator” rained upon him. Undeterred, he wielded extraordinary power in three directions: toward the soldiers, the subversives, and the slaves. Yet even as, in his hands, the national government enlarged its powers, it did so under iron constraint, thanks to the judgment, will, and character of the commander in chief.

Running the war: Lincoln and the soldiers

All wars, from the Whiskey Rebellion and Quasi-War with France in the 18th century to Iraq and Afghanistan in the 21st, necessarily enlarge the scope and prerogative of presidential authority. But no war threatened the very survival of the nation like the Civil War. Accordingly, no war witnessed such an expansion of executive power.

Lincoln’s first military decision forced him to navigate through conflicting advice from his commanding general, the legendary Winfield Scott, and assorted politicos and pundits. All assumed the novice president incapable of judging the proper response to the growing crisis. The issue at hand was Fort Sumter, a weakly manned coast defense bastion in the middle of Charleston harbor, now threatened by South Carolinians on shore, not an invader from the sea. Against those who would evacuate and those who would reinforce, Lincoln, with deft political instinct, took the middle (and morally and constitutionally high) ground by merely re-provisioning the besieged fort without provocatively sending fresh troops. He was pledged to maintain, he insisted, federal control over federal property and forces. His decisive but measured initiative forced the hand of the southerners, who blasted the little island into rubble and surrender — thereby unambiguously firing the first shots in an insurrectionary act against constituted authority.

Lincoln responded with a summons for a mighty federal force — 75,000 soldiers to swell the 16,000-man U.S. Army — to suppress the rebellion. He called out the state militias, augmenting them with volunteers. He insisted — as many officers resigned their commissions to join the rebel forces — that remaining officers swear a new loyalty oath, and paid for it all with deficit financing with no appropriation from lawmakers. He proceeded to proclaim a blockade of southern ports (tantamount by international law to a declaration of war). He unilaterally banned “subversive” materials from the mails.

And he did it all without any congressional authorization ... for Congress was not in session!

To his credit, he did call senators and representative back to Washington for an emergency session. And then he turned his attention to running the war. But his military experience was limited, by his own wry admission, to battling, unsuccessfully, great hordes of mosquitoes during the Black Hawk War three decades earlier. Thus as a military leader Lincoln was completely self-taught. Initially a hesitant novice, he quickly showed, according to his young aide John Hay, “great aptitude for military studies.” He read. He conferred. He pondered. He spent long hours at the side of War Department telegraphers, reading the latest battle dispatches. He visited the Union camps, winning the enthusiastic loyalty of common soldiers. And he moved ever more decisively to provide overall strategic direction to the burgeoning federal land and sea forces.

By late 1861, exasperated with the halting generalship of his top commanders, Lincoln had become his own general in chief. Ultimately he would out-general his Confederate counterpart, West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran Jefferson Davis.

Yet even in orchestrating the war, Lincoln operated within what he accepted as constitutional bounds. The most active commander in chief in American history both defined the role expansively and limited it securely.

Running a war from the White House was startling enough. But bound up in his management of federal armies was a determination to avoid losing the North while prevailing in the South. That meant wielding the immense clout of his office against those sometimes hailed as American heroes: political critics and antiwar dissenters.

Repressing dissidents: Lincoln and the subversives

Even before his inauguration, Lincoln’s situation had seemed dire. The president-elect had to be spirited into the Federal City in the dead of night, his life reportedly in peril from Southern sympathizers in the North. The federal government faced outright isolation if south-leaning elements in bordering Maryland, a slave state, had their way; for a time, Marylanders successfully cut the rail lines that connected the capital to the loyal North.

Shaken but decisive, the new president moved swiftly to outmaneuver the subversive schemes of Confederate sympathizers. He suspended habeas corpus, the basic right to be charged and tried. When John Merryman, an outspoken pro-southern activist in Maryland, recruited a volunteer company to fight for the Confederacy, the Army seized and held him. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney ordered a hearing, but neither the military commander nor the president paid any attention.

Taney responded with a blistering judicial opinion condemning Lincoln’s arbitrary action. Lincoln continued to ignore him.

The bold, unprecedented initiatives of a president claiming vast powers as commander in chief elicited criticism enough. But there was yet another blockbuster act to come, before which all others paled: confiscating rebel property unilaterally and universally.

Or, put in more human terms: freeing the slaves.

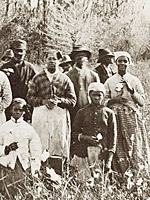

Releasing the bondsmen: Lincoln and the slaves

The Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln’s boldest expansion of power as commander in chief — and his supreme legacy — today seems timeless, morally imperative, disconnected from its grounding in military necessity. The Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln’s boldest expansion of power as commander in chief — and his supreme legacy — today seems timeless, morally imperative, disconnected from its grounding in military necessity.

But in its day the proclamation seemed something like a legal sleight of hand in the service of a higher law. Except Lincoln resolutely argued that emancipation was no more than a legitimate measured extension of presidential war power in the face of mortal danger to the Constitution, and an action vindicated by its impact on both the battlefield and on the subsequent progress toward full abolition.

Lincoln entered the presidency firm in both hatred of slavery and conviction that only a state could abolish it. In the early days of the fighting, he tried to persuade leaders in loyal slave states such as Maryland to begin a phase out of the institution, perhaps by federally subsidized payment to slave owners. That was all he could do, he at first believed, despite pressure from antislavery advocates at home and even abroad.

Yet by late summer 1862, Lincoln had decided to free slaves as a “fit and necessary war measure.” So on New Year’s Day 1863, he signed the Emancipation Proclamation, a military order declaring slaves in rebel hands forever free. He had come to recognize the distinct advantage the rebel armies gained by using slaves to do jobs that released their owners to fight. Seizing such strategic property as “contraband of war” would turn the advantage northward.

Only a state government could end slavery. But he, as commander in chief, in one more bold extension of his powers, could free the slaves of rebels on the sole grounds of military necessity. The moral deed, a constitutional amendment to abolish all slavery everywhere in the Republic once for all, would follow in due course.

A presidential independence day?

Commander in Chief Abraham Lincoln not only initiated a war without authorization from the legislative branch, but he also curtailed the civil liberties of U.S. citizens in open defiance of the chief officer of the judicial branch. And he used a military order to seize private property. In our post-9/11 world, does this kind of blatant executive action sound uncomfortably familiar? Is it any wonder that the press, politicians, legal authorities, and even ministers, then as now, blasted such breathtaking exercise of executive power?

How could a president justify these extraordinary actions as commander in chief?

Lincoln made his case early on, in that Fourth of July message to Congress. It is not too much to say his argument constituted a kind of declaration of presidential independence.

And, at the same time, presidential dependence.

He began by raising anew the long-cherished hope that America might be a model and beacon to “the whole family of man.” If this was grandiosity, for Lincoln it was also earnest vision: that all humankind might be inspired to embrace a governmental system of, by, and for the people, in order “to elevate the condition of men ... to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all ....”

Representing the people whose “ballots have fairly and constitutionally decided” the nation’s course, pre-empting any “appeal back to bullets,” Lincoln professed only to have “done what he has deemed his duty.” That necessary performance entailed “no choice but to call out the war power of the Government, and so to resist force, employed for its destruction, by force, for its preservation.” And thus his actions, “whether strictly legal or not,” were so necessary “that Congress would readily ratify them.”

In short, Lincoln freely confessed he had acted independent of Congress. Yet he hastened to call for retroactive confirmation, thus reinstating a kind of dependence on the legislative branch. I have done my oath-bound duty, he concluded. “You will now, according to your own judgment, perform yours.”

A case for presidential power

During the Civil War, and periodically since, Lincoln’s executive actions as wartime commander in chief have been branded “dictatorial,” often as criticism, sometimes as commendation. We, however, must finally appraise Lincoln not only for his acts, and his rationale for them, but also for how and why he tempered his actions. “In his ability to combine ruthless pragmatism and a deep fidelity to principle,” concludes Daniel Farber, he may have been unique. “It was Lincoln’s character — his ability, judgment, courage, and humanity — that brought the Union through the war with the Constitution intact.”

Hence, even if we worry about certain precedents Lincoln set in wielding power as commander in chief, we can celebrate the precedents he set, as a leader both pragmatic and principled, for constraining that power.

Dictatorial? No, not when one acknowledges what he didn’t do. And Lincoln himself would have none of it. He premised his acts on his oath to preserve and defend the Republic’s charter, an oath he would violate if he did not act. Further, as he argued in 1863, the text of the Constitution recognizes that “cases of Rebellion and Invasion” demand actions not appropriate in less threatening times. In short, “by the Constitution itself, things may be done in the one case which may not be done in the other.”

But he was not naïve. He knew any leader’s actions would provoke opposition. That’s the price of statesmanship. In an 1864 letter he baldly explained that “measures, otherwise constitutional, might become lawful, by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the constitution, through the preservation of the nation.” If you lose the nation, you’ve lost the constitution. So let the statesman act, held Lincoln. Just be ready for the people to dissent from your actions, and turn you out of office at their regular quadrennial opportunity.

Such was the case for presidential power laid out in that first address to Congress on July 4, 1861.

And it raises issues still relevant today. What will we tolerate, on what constitutional grounds, from our president today? Detention of suspected terrorists? Pre-emptive military action? Assassination air strikes in a friendly foreign country? Bank bailouts? Circumvention of a court order to ban or permit stem cell research? And how much of that tolerance depends on citizen confidence in the president’s character?

Accepting the duty to be president of all citizens (even those in rebellion), to act by their authority to preserve their constitutional government, but to be accountable to their will for their good, President Lincoln, even in his role as commander in chief, embodied the ideals of the Constitution he revered, and restricted his own power by the strength of his character, as a servant of the people.

Or, as Lincoln himself put it, in the final sentence of his brief address at Gettysburg: Let all Americans honor their fallen defenders by ensuring “that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, will not perish from the earth.”

Professor of History William Woodward joined the Seattle Pacific University faculty in 1974. He specializes in the history of the Pacific Northwest, especially military history, as well as 19th century American culture. The recipient of numerous grants and honors, Dr. Woodward also gives public lectures on history and is a consultant to school districts and historical societies. Professor of History William Woodward joined the Seattle Pacific University faculty in 1974. He specializes in the history of the Pacific Northwest, especially military history, as well as 19th century American culture. The recipient of numerous grants and honors, Dr. Woodward also gives public lectures on history and is a consultant to school districts and historical societies.

For information about the U.S. Constitution and about Constitution Day, September 17, visit the National Constitution Center.

SPU >> Response >> Exclusives |