By Phillip Goggans,

Photos by Jimi Lott

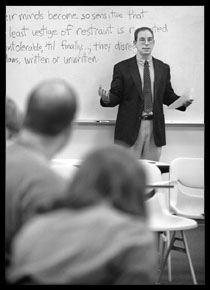

Assistant Professor of Philosophy![]()

![]()

"We have been trying, like Lear, to have it both ways: to lay down our human prerogative and yet at the same time to retain it."

C.S. LEWIS

THE ABOLITION OF MAN

Shakespeare's King Lear tried to cast off the responsibilities of his office but retain its glory. He ended up homeless, isolated, despised, persecuted, exposed to the elements. Modern man, says C.S. Lewis in The Abolition of Man, is making the same mistake.

Kings have no choice but to fulfill the duties of the office they inherit. Likewise, argues Lewis, human beings have an "office" with moral responsibilities they cannot define or reject. Attempts to change these responsibilities result in abdication, a giving up of one's humanity.

The Abolition of Man, originally composed as a series of three lectures delivered at the University of Durham in February 1943, is one of more than a dozen works of Christian apologetics written by Lewis. Says Chad Walsh, author of The Literary Legacy of C.S. Lewis, "At the opposite extreme from his soaring feats of imagination are those books in which Lewis aims directly at instruction and even conversion. These are the apologetic works par excellence."

In this brief but challenging book, Lewis examines what happens if we reject the moral law that all civilizations have to some degree taught and embodied. He argues that if we refuse to submit to it, either by asserting the authority to change it or by denying its existence altogether, we become less than human. For human life, he says, is civilized life, and civilization is only possible where there is submission to the moral law.

Lewis intentionally does not bring the language of theism into The Abolition of Man. His goal is not to argue for the existence of God, but for the existence of an absolute moral order. In other works, such as Mere Christianity, he takes the argument in a different direction, to "what lies behind the law" and the case for the existence of God.

"By starving the sensibility of our pupils we only make them easier prey to the propagandist when he comes. For famished nature will be avenged and a hard heart is no infallible protection against a soft head."

Lewis begins the first lecture in The Abolition of Man by challenging two elementary textbook authors he calls "Gaius" and "Titius," who claim that our moral and value judgments are simply misleading ways of describing our personal preferences. According to Gaius and Titius, when we say, for example, "The waterfall is beautiful," we are merely saying that we like the waterfall, that it pleases us. We only appear to be describing the waterfall. The general implication of this view is that there are no objective facts about value.

Lewis knows better than to treat this moral subjectivism as a philosophical theory about moral discourse, or even as an attack on moral judgment per se. He sees it for what it is: an attempt to undermine respect for moral judgments that the subjectivist doesn't like. "In actual fact, Gaius and Titius will be found to hold, with complete uncritical dogmatism, the whole system of values which happened to be in vogue among moderately educated young men of the professional classes during the period between the two wars. Their scepticism about values is on the surface: It is for use on other people's values. About the values current in their own set they are not nearly sceptical enough."

Lewis goes on to take up the real issue: the attempt to found a new morality. He considers what would happen if Gaius and Titius tried to clear away old values to make room for new ones. They could not succeed, he says, because the process of "debunking" what they view as contemptible sentiment would inevitably destroy the very capacity for living in a truly human way. "Do what they will, it is the 'debunking' side of their work, and this side alone, which will really tell."

For to live rightly, argues Lewis, it is not only necessary to believe correctly about right and wrong; one must feel correctly as well. Pride, shame, indignation, compassion and other emotions must support reason against the demands of the animal appetite. Education should nurture these feelings, teaching children to love what deserves love, hate what deserves hate, and so on. Subjectivism, however, weakens passions indiscriminately, producing "men without chests" or men without "fertile and generous emotions."

If Gaius and Titius seek to protect against fanaticism, their tactics are misguided, says Lewis. "The right defence against false sentiments is to inculcate just sentiments. By starving the sensibility of our pupils we only make them easier prey to the propagandist when he comes. For famished nature will be avenged and a hard heart is no infallible protection against a soft head."

"What purport to be new systems or (as they now call them) 'ideologies,' all consist of fragments from the Tao itself, arbitrarily wrenched from their context in the whole and then swollen to madness in their isolation..."

The second lecture in The Abolition of Man contains a fascinating argument that the judgments of the Tao — Lewis' term for traditional morality — stand or fall together.

Lewis documents the existence of the concept of the Tao in Christian, Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoic and Eastern thought. It has at its core, he says, "the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are."

Lewis argues that we may not pick and choose among the values of the Tao, or "Law of Nature" as he describes it in Mere Christianity. If we do, we set ourselves in authority over the Tao. And so we reject its authority over us.

The success of his argument depends on whether there is such a thing as the Tao. Others look at the vast array of value systems spanning times and cultures and see only conflict and confusion. Lewis sees a living, unified body of values. The Tao develops, but in accordance with its own principles. No one has the authority to act upon the Tao; one can only act for it, implementing changes that it calls for. Genuine moral progress happens by virtue of the Tao, not by virtue of the "enlightened" insight of people who have rejected it.

What claim to be new systems of morality, says Lewis, are unavoidably mere fragments of traditional morality, separated from the whole and given a false emphasis. "What purport to be new systems or (as they now call them) 'ideologies,' all consist of fragments from the Tao itself, arbitrarily wrenched from their context in the whole and then swollen to madness in their isolation, yet still owing to the Tao and to it alone such validity as they possess."

It would be difficult to find a more illuminating statement on the nature of fanaticism.

"In the Tao itself, as long as we remain within it, we find the concrete reality in which to participate is to be truly human: the real common will and common reason of humanity, alive, and growing like a tree, and branching out, as the situation varies, into ever new beauties and dignities of application."

In the final and most difficult lecture in The Abolition of Man, Lewis considers the consequences of rejecting objective value altogether. He imagines the human race saying, "Let us decide for ourselves what man is to be and make him into that; not on any imagined value, but because we want him to be such. Having mastered our environment, let us now master ourselves and choose our own destiny."

Using a mixture of metaphor, history and futurology, Lewis argues that when human beings assume the authority to control moral law, they forfeit their humanity. Their bid for ultimate freedom makes them slaves to their purely animal natures.

We cannot take for granted our knowledge of what it is to be human, says Lewis. It is the product of centuries of experience, reflection, suffering and dialogue with God. It is kept alive from generation to generation by example, custom, art and literature. If we lose it, in a very real way we lose our lives.

The drive to abandon the moral law Lewis sees as essential to humanity is everywhere evident. In the Republic, Plato claimed that this was characteristic of democratic cultures. "Their minds become so sensitive that the least vestige of restraint is resented as intolerable, till finally … in their determination to have no master they disregard all laws, written or unwritten."

The Abolition of Man is a Republic for our day. Like Plato, Lewis argues that to live rightly is much better than to live wrongly. "In the Tao itself, as long as we remain within it, we find the concrete reality in which to participate is to be truly human: the real common will and common reason of humanity, alive, and growing like a tree, and branching out, as the situation varies, into ever new beauties and dignities of application." The image of a torch relay race at the beginning of the Republic announces its central theme: the transmission of the knowledge and sentiments that make human life possible. It is no accident that a torch is also the official logo of Seattle Pacific University. Since there are always some who attempt to subvert the principles on which society rests, there must always be others who cherish them, study them and pass them on.

After his introduction to Lewis at Paintsville High School in eastern

Kentucky, Goggans went on to earn a bachelor's degree in biblical languages

from Asbury College, a master's degree in philosophy from the University of

Kentucky, and a doctorate in philosophy from Syracuse University.

At Seattle Pacific since 1993, Goggans specializes in ancient philosophy and

natural law theory. He introduces students to The Abolition of Man,

recognizing that "it's a tough read for everyone."

One difficulty, he says, is that students have a hard time

believing anyone would seriously embrace moral subjectivism. "Students greet

moral subjectivism, which Lewis criticizes, with

incredulity," he says. "They're happy about his opposition to it, and

they're sympathetic to his claim that it's simply a ploy to

discredit certain moral judgments. The Abolition of Man is full of

wonderful insights, which they greatly appreciate."

Goggans, too, appreciates Lewis' depth of insight. "I learn new things every

time I read it." About the Author:

About the Author:

"I discovered the works of C.S. Lewis in high school," recalls Phillip

Goggans, Seattle Pacific

University assistant professor of philosophy. "I know I read The

Abolition of Man then because I remember quoting it in a paper I wrote

as a senior — not that I

understood it."

![]()

| Please

read our

disclaimer.

Send any questions, comments or correspondence about Response to

jgilnett@spu.edu or call 206-281-2051. Copyright © 2000 University Communications, Seattle Pacific University.

Seattle Pacific University |