This hand-drawn map by Augustus Koch shows a “Birds-Eye View of Seattle and Environs” in 1891, the year of Seattle Seminary’s founding. Classes did not begin until 1893, the year Alexander Hall was completed. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

Response Gallery: Sent Out From This Place | Click + to zoom.

Sent Out From This Place

From Its Earliest Days, Seattle Pacific Has Sent Graduates Into a “Life Lived for Others”

By Hannah Notess | Historical photos courtesy of the Seattle Pacific University Archives

“Teacher. Missionary. Preacher. Evangelist.” These were the intended professions listed under the names of the 13 graduating college seniors in the 1924 Cascade yearbook of Seattle Pacific College.

In 2013, 1,208 undergraduate and graduate students were eligible to participate in Commencement exercises at Key Arena in Seattle. Some will become educators. Some will become clergy. But others will become businesspeople, nurses, engineers, graphic designers, psychologists, novelists, school superintendents, dietitians, zookeepers, cancer researchers, photographers, entrepreneurs, and professionals in every field. And, if U.S. Department of Labor statistics are any indication, they may hold more than 10 different jobs during their lifetimes.

How “a Christian school where pupils are to be trained and educated for the work of proclaiming the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ in foreign countries” — as founder Nils Peterson wrote when he donated his five-acre garden plot in 1891 — became a comprehensive university with more than 4,000 students in the liberal arts and professions isn’t a story that can be fully told here.

But a glimpse into the history of Seattle Pacific University reveals an ongoing clarity of vision for sending graduates into the world to do good. It’s a vision that has remained remarkably constant through sweeping cultural, economic, scientific, and technological changes over 122 years.

The small group of Free Methodists who founded what was then called Seattle Seminary had little formal education themselves, yet were insistent on forming a school, notes Donald McNichols in his history, Seattle Pacific University: A Growing Vision 1891–1991. In doing so, they were part of a larger Wesleyan movement sweeping the U.S. toward the end of the 19th century.

Across the country, religious training schools were being founded by Wesleyan men and women to train young people for Christian service. These schools typically combined religious education with a broader course of study, including vocational training, says Priscilla Pope-Levison, SPU professor of theology, who studies American religious history, mission, and evangelism.

You could say that education in service to others is in SPU’s institutional “DNA.” Here are just a few memorable moments in a long history of engaging the culture and changing the world.

1891

Seattle Seminary is founded.

1893

Seattle Seminary registers 34 students in a college preparatory curriculum that includes primary and intermediate grades.

1910

Seattle Seminary begins offering college-level courses.

1915

With the graduation of its first college students, Seattle Seminary officially becomes Seattle Pacific College.

1918

SPC’s first Psychology Department — the forerunner of today’s School of Psychology, Family, and Community — is founded.

1921

Seattle Pacific founds a Normal Department or teacher-training program. Since then, thousands of educators have been sent out into schools by SPU.

1922

Margaret Matthewson McCarty ’23 completes 10 years of secondary and college education at Seattle Pacific and becomes a teacher. She is later a missionary to Sierra Leone, SPC’s first female trustee, and the first woman to be named SPC’s Alumna of the Year.

1933

Seattle Pacific receives approval from the Free Methodist Church for intercollegiate athletics. Today, SPU’s NCAA Division II athletes are known for their success in competition and in the classroom.

1936

The College’s four-year liberal arts program is accredited by the Northwest Association of Schools and Colleges. The liberal arts will remain the cornerstone for all students educated and sent out from Seattle Pacific.

1938

The School of Nursing Education is founded. Known for skill and compassion, SPC nurses apply their education regionally and internationally — as they do today.

1945

SPC choirs perform on the “Light and Life Hour” radio program under the direction of Lawrence Schoenhals — reaching radio audiences across the country.

1948

Jacob DeShazer ’48, former Doolittle Raider and WWII POW of Japan, sets sail for Japan. There, he and his wife, Florence Matheney DeShazer ’48, are missionaries for 30 years.

1955

Seattle Pacific acquires 155 acres on Whidbey Island — Camp Casey — a former military facility purchased from the U.S. government. Casey now hosts SPU students and nonprofit groups for field study and outdoor education throughout the year.

1960

Ernest Thayil ’62 conceives of the idea for Operation Outreach, a short-term summer mission trip for students. The tradition continues today through SPRINT, Urban Involvement, and other programs.

1961

SPC founds a Theatre Department, helping to cast a vision for faith and the arts.

1962

During the Seattle World’s Fair, SPC develops summer school courses and lectures for those visiting “Century 21.” The “Christian Witness Pavilion” at the fair is dedicated with a speech by SPC President C. Dorr Demaray.

1966

Doris Brown Heritage ’64 becomes the first woman to run a sub- 5-minute mile indoors (at 4:52). She goes on to compete in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.

1974

David T. Wong ’61 and fellow scientists at Eli Lilly Company discover the drug Prozac, today a medication commonly prescribed for depression.

1977

Seattle Pacific College officially becomes Seattle Pacific University.

SPU’s School of Business and Economics is founded, earning a reputation for educating graduates with solid business ethics.

1979

Lora Jones ’43, also known as Zhou En-Ying, a missionary in China, is released from decades of imprisonment under Communist rule. She continues to preach and teach.

1987

Larry Wall ’76 develops the computer programming language PERL, informally known as “the duct tape that holds the Internet together.”

1993

The New Testament portion of The Message, the popular paraphrasing translation of the Bible by Eugene Peterson ’54, is first published.

1997

Julie Anderson Lamb ’97 becomes SPU’s first Fulbright scholar, traveling to Zimbabwe to research drug-resistant TB and meningitis.

2000

SPU music groups present the first Sacred Sounds of Christmas concert in downtown Seattle, following a long tradition of Seattle Pacific musicians performing for the benefit and enrichment of the city.

2003

Acting on AIDS is founded by SPU students Lisa Krohn Haggard ’04, James Pedrick ’04, and Jackie Yoshimura ’04. The student club has grown into World Vision ACT:S, a network of more than 30,000 young Christian advocates around the world.

2004

The John M. Perkins Center for Reconciliation, Leadership Training, and Community Development is founded at SPU.

2006

A $1.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation helps to fund research on more effective science teaching methods and improved science literacy.

2010

Following the Haiti earthquake, Professor of Clinical Psychology John Thoburn helps train Haitians to provide psychological first aid. In 2012, the American Psychological Association gave him their International Humanitarian Award.

2012

The first class of master of divinity students graduate from Seattle Pacific Seminary, going out to serve as pastors and in other forms of ministry.

This timeline barely scratches the surface of “memorable moments” in the rich history of SPU’s mission. Tell us what events or stories you’d add.

Two 19th-century evangelists, Emma and L.P. Ray, met students from Seattle Seminary while doing evangelistic work in Seattle jails. This encounter led the Rays, who were African American, to join the white Free Methodist Church in Seattle and cross racial barriers with “holy boldness” to minister among the poor, sick, and suffering in Seattle.

“Their decision was remarkable and highly unusual for this time in American history,” says Pope-Levison, who spoke about Emma Ray’s ministry in the 2013 Paul T. Walls Lecture: “Holiness in Black and White: Women, Race, and Sanctification.” And a sanctification-inspired mission to serve the poor, she says, was typical of the Free Methodist Church — as well as Seattle Seminary. The “free” in “Free Methodist” was, in part, a stand against slavery. But it also meant “free pews,” so that people didn’t have to pay to sit in church — anyone was welcome.

Of course, along with serving city residents, foreign mission was deeply important for students in the early decades. As Seattle Seminary became Seattle Pacific College in 1915, it was training many for worldwide service. SPC’s then-remote location in Seattle was ideal for reaching Alaska and the Pacific Rim.

“Fifty percent of our college department (sic) have answered the challenge to world evangelism, and deep in the heart of every one is the consciousness that the life that counts is the life lived for others,” wrote Frank Warren ’22 in the 1922 Cascade yearbook. Shortly thereafter, he and his wife, Lucille, set sail for Japan to become missionaries themselves.

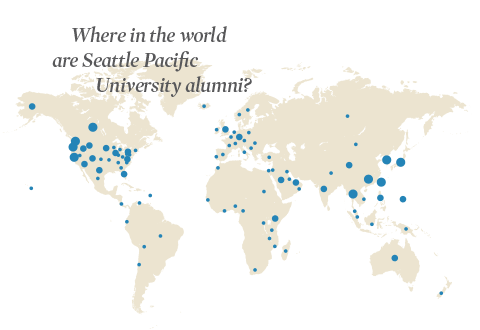

“Some of our students are serving in Africa, some in India, some in Alaska, some in Central America, some in China, and some in Japan,” reported the 1925 Cascade. “These fields are naturally the most familiar to our students, for our chapel walls are decorated with charts and maps that give the names and the location of each SPC student now on the field.”

In addition to an emphasis on foreign service, an emphasis on academic and vocational training based on the liberal arts gradually emerged over the first few decades.

The school curriculum had always been based on the liberal arts, but under President C. Hoyt Watson, SPC became “the college which gives an Education-Plus,” meaning that education was central, but Watson also intended for students to have “a full-orbed Christian personality,” as he put it.

The post-World-War-II years saw explosive growth. An industrial arts department, a school of recreational leadership, an international school of missions, and even a flight school were launched to meet the needs of the returning veterans that dramatically boosted college enrollment. These veterans brought a new character to the student body, remembers Norma Howell Cathey ’50.

“Our class was full of leaders and full of creativity,” she says. Editor of the Falcon and president of the Associated Women Students, Cathey says those leadership roles on campus were “half her education.”

“It wasn’t just a frivolous thing. Students took those leadership roles and became leaders in secular occupations or in the church. And all of them are still serving their churches. They’re not just warming the pews.”

Married on the evening after graduation, Norma and her husband, Robert Cathey ’50, were sent out from Seattle Pacific to become public school teachers, including a stint teaching in Japan and Germany.

“At SPC we were prepared to be citizens of the world,” she says.

Though the flight school quickly became too expensive to maintain, and industrial arts was folded into the engineering program, growth only continued in following decades, with a renewed emphasis on a liberal arts curriculum — and on Christian commitment put into practice for the benefit of others.

“It is necessary for us to prepare men and women for a world that does not yet exist, and to do so in an era of exploding knowledge. To do this will require us to provide an education beyond the facts,” wrote C. Melvin Foreman ’42, as dean of students, in the Autumn 1964 SPC Alumni News.

“We at Seattle Pacific aspire to give to our country and the world educated men and women of character,” he continued. “In a sentence, our purpose as a college is to see that the men and women of Seattle Pacific become whole in both competence and conscience.”

By the time Seattle Pacific College became Seattle Pacific University in 1977, the name change reflected what it had already become: an institution preparing both undergraduate and graduate students for lives of Christian service in both religious and secular careers.

Likewise, then, the language of “engaging the culture and changing the world” introduced in 2002 was not only a vision for the University’s future, but also a reflection of what had happened, what was happening, and what continues to happen today — through graduates sent out into the world.

The city of Seattle, once an outpost valued for its proximity to Alaska and to the Pacific Rim, has become a thriving metropolis — but also a wilderness of a different kind. Now, SPU lies in the middle of “the None Zone,” a term coined by religion researchers to describe the part of America where the greatest number of people answer “none,” when asked about their religious affiliation.

David Haslam ’09, MDiv ’12, finds he must leave the comfort of his office to minister to the “nones” as a youth pastor at Lakeview Free Methodist Church in Seattle.

“We have to go outside of the church walls; we can’t stay inside anymore,” he says. “It is not waiting for people to come to church, but going out to where they are in their lives.”

Trained for ministry at Seattle Pacific Seminary in SPU’s School of Theology, Haslam says he was prepared to put his seminary education to use for the benefit of others. And, as a fourth-generation alumnus, he imagines the founders would be proud of the current generation of Seattle Pacific graduates.

“If they saw what alumni have gone out and done in the world, I think they would be very happy,” he says. “They are engaging the culture and changing the world — and doing that in the name of God.”

Comments

Rev. Dr. Craig McMullen '79

Posted Saturday, July 27, 2013, at 12:31 p.m.

A note I wish to add to the SPU timeline: In 1978, the Lord spoke to me about creating a student-led worship service on Sunday nights entitled “Celebration.” President McKenna allowed a group of us to use Gwen Commons for this gathering, which grew to over 1,000 students attending each week. Out of the Celebration service a renewed movement for student missions grew — specifically among the urban poor. It is my understanding that this same student-led worship service continues on campus to this very day under the title "Group." I thank the Lord for using SPU to launch me into the past 35 years of Christian ministry. May the Lord continue to bless Seattle Pacific! Rev. Dr. Craig W. McMullen ’79, Senior Associate Pastor of The Potter's House in Denver.