Web Feature Posted October 3, 2013

Constitution Day 2013: Preacher Lincoln’s Constitution

and the Dependence on the Declaration

By William Woodward

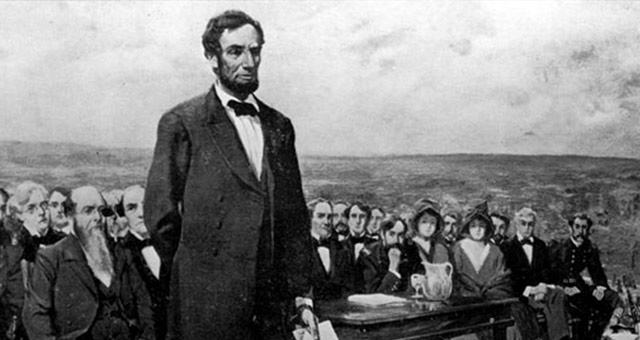

President Abraham Lincoln delivering the Gettysburg Address, Thursday, November 19, 1863, at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Eleven score and seventeen years ago, our forebears brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all are created equal.

Precisely 150 years ago, a president — who revered what was done in 1776 — evoked the Spirit of ’76 to honor the fallen of Gettysburg. In so doing, he elevated and reinterpreted what historian Pauline Maier calls “American Scripture”: the Declaration of Independence, with its timeless expression of the core American values of freedom, equality, and self-government.

Not lost on those who heard Abraham Lincoln’s Address at Gettysburg in November 1863 was the fact that the president had within the year freed the slaves with the stroke of his pen — on grounds of military necessity, yes, but more fundamentally because he believed they too were “endowed by their creator” with the right to liberty, and the equal right to sell their labor rather than give it under coercion.

Perhaps less obvious to that audience was his implicit challenge to complete “the unfinished work” of devising explicit Constitutional guarantees to bring practice into alignment with the nation’s founding ideals.

Today’s Constitution Day reflections on the Gettysburg sesquicentennial resume an annual series, and specifically return to the linkage among Abraham Lincoln, his storied address, the Constitution, and the Declaration of Independence. Lawyer Lincoln deeply respected the Constitution. But to him it was not so much foundational holy writ as it was implementing instructions. For Lincoln, the authoritative scripture was the Declaration of Independence. So this year we read our Constitution in the context of the Declaration.

In short, on this Constitution Day 2013 we need to view our Constitution through Lincoln’s eyes — as the 1787 charter implementing the 1776 Declaration, as preached by the 16th president in his 1863 Address.

The Gettysberg Gospel

Or maybe we should call it his Gettysburg Sermon. Indeed, the distinguished Civil War historian Gabor Boritt titles his account of the address The Gettysburg Gospel. It’s more than a metaphor; Boritt presents Abraham Lincoln as a truly persuasive proclaimer of fundamental truth.

To understand Preacher Lincoln, we must grasp a triad of undergirding principles that shaped his life and thought. He was, first of all, a disciple of improvement, the central mantra of his age. First for self, but then for society, one must constantly strive for something better. And the impoverished youth who became in turn muscular rail-splitter, successful lawyer, brilliant rhetorician, and president embodied his age as none other.

Second, the possibility of improvement stemmed, Lincoln believed, from the fundamental ideals articulated by Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration at the moment of America’s birth. Throughout his political career Lincoln relentlessly and uncynically celebrated the Declaration’s lofty notions of liberty and equality.

But thirdly, these were filtered through a simple yet developing spiritual instinct centered on a providential God revealed in the Bible. Not a “technical Christian,” as his wife Mary fully conceded, Lincoln still was profoundly shaped by the Bible’s moral codes and cadences he imbibed in his youth. Despite few connections to formal religion, he harbored in his soul a profound awareness of the mysterious providence of the Almighty. He thus could readily communicate to his Christian constituents, especially evangelical Midwesterners, in biblical sentences; he became an expositor of political scripture in classic evangelical style.

Thus it is not too much of a stretch to regard Lincoln, with Boritt, as a preacher of an American gospel (or “evangel”) of liberty and equality, and more specifically as a practitioner of a distinctively evangelical kind of sermonizing. That style classically calls for three elements: “exegesis,” or a deep explanation of the meaning of the biblical text; “exposition,” or the elaboration of the breadth and nuances of that text, and “exhortation,” the call to the hearers to change in response to the message of the expounded text.

The Gettysburg Address may, in fact, be read as a sermon, ranging from past to present to future: first with an exegesis of the Declaration’s precepts (which “our fathers brought forth”), then an exposition of the meaning of those precepts in the testing time of Civil War (when we have “come to dedicate a . . . field”), then a challenge to future faithful action (by “us the living”).

A sermon, but not just for its own moment. The Gettysburg Gospel speaks to us still, indeed lives on in a prominence that would have astounded both Lincoln and his audience, because of several characteristics. As historian Eric Foner stresses, it is national in its vision and biblical in its rhetoric, without confusing the two. It is liberal in the old-fashioned sense of extolling individual freedom. Yet it is more broadly and deeply philosophical than that, capturing the people-focused underpinning of democratic government. And finally it is empathetic, respecting the dead and engaging the living, especially the grieving families and the liberated slaves.

It speaks because it is indeed the essential commentary on the Declaration.

The Dependence on the Declaration

As I explained in the first of this series in 2008, Lincoln emerged in the decade before the Civil War as a nationally recognized uncompromising critic of slavery. He blasted black bondage as a “chronic blight on the essential purpose” of America. He lambasted those who would allow slavery to expand into the West, thereby distorting the intent of the Constitution and violating the great ideals of the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln’s Constitution, like Lincoln’s Declaration, embodied basic principles of humane values; loyalty to the founders and the principles of 1776 was therefore a solemn duty.

British historian Richard Carwardine argues that it was this “moral and philosophical clarity” that made his rhetoric compelling. He offers the most forceful and persuasive analysis of Lincoln’s foundational views, stressing Lincoln’s reverence for the charter documents. “The Declaration of Independence, with its philosophical celebration of equality and liberty, and the federal Constitution, the legal guarantor of those principles,” as Richard Carwardine writes, were for Lincoln “measures of American uniqueness.”

But the Declaration was prior.

Lincoln proclaimed that it stood as a “standard maxim for free society . . . to all peoples, of all colors, everywhere” — as he lectured Stephen Douglas in their famous debates. It was the “sheet anchor of American republicanism,” a universal moral system rooted in free labor. It embodied “truth, and justice, and mercy, and all the humane and Christian virtues.” The natural right of liberty was America’s “first cause,” Lincoln wrote, “which clears the path for all and gives hope to all and, by consequence, enterprize, and industry to all.”

No less for persons than for nations was the natural right to free and equal government by consent of the governed. Indeed, liberty and equality, the legacy of the founders, offered a potential model for all peoples.

Accordingly, Lincoln rejected any reading of the Constitution that contradicted the Declaration — such a view would be unconstitutional, we could say, because it was “undeclarational.” Specifically, he excoriated Southerners who tried to find positive protection for slavery in the Constitution.

We in our day, so removed from 1776 and perhaps so jaded by insincere rhetoric, claim the Declaration of Independence at a distance and in moderation, unlike Lincoln and his audiences. It is hard for us to grasp how resonant his Gettysburg Address was, and therefore how sermonic its appeal. Hold fast, Lincoln in effect was pleading, to the Cause that the Northern military effort, bloody as it was, embodied. For it is the Cause of America’s founding and therefore the Cause of all humanity.

In short, Lincoln called Northerners, and intended to call us, to a “new birth” of the freedom at the core of Jefferson’s Declaration. Martin Luther King, in his legendary 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, thus rightly quoted the Declaration at the Centennial of the Gettysburg Address.

Accordingly, let us ponder certain of Lincoln’s phrases as they both evoke universal principles and gloss the implementing Constitution President Lincoln had sworn to uphold — yes, uphold in the face of insurrection.

The Phrasing of the Fusion

Lincoln apparently wrote his remarks at the last minute (though not, as legend has it, on the back of an envelope en route from Washington). But as was his usual practice, he had pondered for weeks ahead what he wanted to convey.

In particular, two central and interlocking commitments guided him. The first, of course, was his lifelong devotion to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence. But the second was his conviction, growing since 1862, that freeing the slaves through the Emancipation Proclamation would be his chief legacy. Carwardine thus rightly identifies “his fusion of Jeffersonian and scriptural precepts, set in the context of Whiggish self-improvement,” as the linchpin for a vision of America as “the last best hope of earth,” as he had said in defense of his Proclamation.

The fusion shines through in memorable phrases from the Address:

- “Our fathers brought forth.” Lincoln revered the founders, and evoked their sainted status in a biblical phrase. America must not squander the sacred trust they bequeathed.

- “A new nation.” What most Americans had called the “Union” (implying the possibility of disunion), Lincoln now provocatively labeled a “nation.” (He used the term five times.) The Civil War, once won, would secure forever the intent of the Founders to create one nation, e pluribus unum: out of many, one. More precisely, that new nation, explains his biographer Ronald White, would rise out of the bloody “purification” of civil war, creating a “new Union and a new Humanity,” forever free of bondage.

- “Testing.” Lincoln saw his presidential purpose as preserving government under the Constitution — even if forced to bend the rules a bit — in order to preserve the government’s undergirding ideals. In his first formal message to Congress he had posed the central question: “Must a government, of necessity, be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?” His answer was that Constitutional government, existing to protect the natural rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” under authority of the “consent of the governed,” could and must rightly take strong measures to suppress a rebellion.

- “Conceived in liberty.” Was Lincoln echoing the Apostle’s Creed (“conceived by the Holy Ghost”)? Quite possibly, if unconsciously. What was conscious was the linkage of Jefferson’s claim for a natural right of liberty and his own increasingly staunch defense of Emancipation. These he now connected to the cause for which the Union dead had fallen: in essence, to restore the Constitutional Union that would operationalize Jefferson’s ideals by securing and extending freedom.

- “All men are created equal.” This was a direct quotation from the Declaration, but like Jefferson, Lincoln was no romantic. With the Americans of his day, he understood equality, as Boritt explains, as the “right to rise in life: equality of opportunity.” That entailed the right to own the return on one’s labor. But Lincoln pointedly included the slave in that right. In a classic argument he had made several times back in Illinois, he insisted of any black woman that “in her natural right to eat the bread she earns with her own hands without asking leave of anyone else, she is my equal, and the equal of all others.”

- “Unfinished work.” In this phrase, reemphasized in the next sentence as “the great task remaining,” Lincoln suggested, as he often did, that what the Founders considered an experiment in self-government remained a work in progress. Increased “devotion to that cause,” that experiment in liberty and equality, would require continued positive measures. The implementing document, the Constitution, would need to be amended, for example. (The 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery altogether, the fight for which was portrayed in Spielberg’s recent Lincoln film, was perhaps already on the Emancipator’s strategic drawing board; I detailed all three post-Civil War amendments in my 2011 essay.)

- “New birth of freedom.” The allusion to the evangelical emphasis on the “new birth” of faith in Christ was subtle; the allusion to the Emancipation Proclamation was unmistakable. Lincoln had fully embraced the logic no less than the tactic of the Proclamation. Freeing slaves had become not merely a “necessary means” for winning the war, but, as Carwardine argues, “one of the purposes of war.” In this, it conformed to the original purposes of the nation’s birth.

- “Of the people, by the people, for the people.” In this final phrase, Lincoln summarized the character of that government-by-consent envisioned in Jefferson’s Declaration, the government whose prime duty was to secure the people’s natural rights. Such government would arise from the people’s choice: It would be representative. It would reflect the people’s will: It would be democratic. And it would be responsive to the people’s sanction: It would be accountable.

The Constitution via the Declaration via the Gettysburg Address

And so, even as we remember Martin Luther King’s Dream a half-century after his great speech at the Lincoln Memorial, let us read anew the words of Lincoln to which King harkened back.

Let us heed Lincoln’s call “for us the living” to tackle the “unfinished work” before us: care for our wounded warriors and their families, commitment to justice for all and especially those descendants of the slaves Lincoln freed, and an engaged citizenship that insists that rule of, by and for the people — idealized in the Declaration, implemented by the Constitution — shall, starting at home, endure.

And let us, on this Constitution Day 2013, reread Lincoln’s storied speech as both a sermon on the ideals our living Constitution ought to fulfill, and a challenge to “highly resolve” to devote our energies to “the great task remaining”:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate — we cannot consecrate — we cannot hallow , this ground — The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us, that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

William Woodward is a professor of history at Seattle Pacific University. This essay was first published on September 17, 2013, in honor of Constitution Day 2013.