Web Feature Posted November 10, 2010

Big-Screen Transformer:

A Conversation With Walden Media Founder Micheal Flaherty

Interview by Jeffrey Overstreet (jeffreyo@spu.edu) | Photos courtesy of Walden Media

What would you ask the man who introduced the world to Narnia, Aslan, the Pevensies, and Reepicheep?

Alas, C.S. Lewis is not available for questions anymore.

But Micheal Flaherty is.

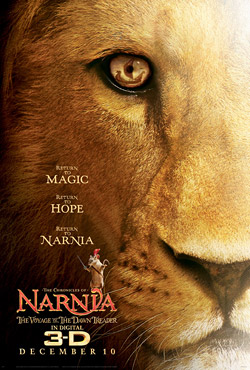

Co-founder and president of Walden Media, Flaherty is currently overseeing his studio's third big-screen adaptation of Lewis's beloved fantasy series. The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader opens December 10, 2010.

After Flaherty's recent visit to Seattle Pacific University, where he spoke at an event hosted by SPU's Center for Integrity and Business and presented a Dawn Treader sneak preview, he took time to answer some questions from Response about the new Narnia film, Walden's vision for improving literacy among children, and the distinctive characteristics of stories Walden chooses to transform into movies.

Watch Flaherty's presentation "Reading and Movies," sponsored by The Center for Integrity in Business

Watch Flaherty's presentation at an SPU chapel gathering, "Prospero's Books: Using Film to Lead People Into a Transformational Love of Literature."

Walden distinguishes itself by making movies that introduce us to excellent literature and inspire us to read. But adapting a novel for the screen is different than crafting an original screenplay. What makes the art of Walden Media's moviemaking different from other studios' methods?

FLAHERTY: When we were first doing The Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe, we had a couple of A-list directors who came in and said, "I read this for the first time. It's a great story. But it really doesn't make sense to have a kids' movie where the lion dies and then comes back from the dead. We should just have him get roughed up a little."

Anytime people want to change fundamental points of the story, that's an immediate red flag.

We love it when a director has some creative ways to address the adaptation of a book into film, because you do have to make changes. As much as we love to talk about being purists, there's a difference between a faithful adaptation and a literal adaptation. We want the changes that they're suggesting and exploring to be faithful to the themes of the book.

First you have to figure out: Why was this story successful? What about this story made people love it, and what are those elements that we have to take the Hippocratic Oath on? What are the things we can't do any harm to?

In the case of the Narnia stories, the first thing we try to do is identify those themes. With Narnia, the key is to identify a lot of Aslan's dialogue in terms of, "What is Scripture? What cannot be changed one iota?" It all starts from the standpoint of "How do we make this truly respectful to the book and to the author?"

But movies are getting faster and faster, more sensational, and now we have 3-D! Reading requires concentration and imagination. How do you make films by today's standards that help develop imagination and deeper thinking instead of prohibiting it?

One thing that really helps us a lot is the example set by Pixar movies.

Our studio partners will try to look for something big to happen in the first act. They'll look for us to set up some things really early so that we can keep kids glued to the screen. They always talk about how, in the day and age of the Xbox and the iPad, you've really got to keep kids' attention glued.

But then we will point to a Pixar movie like Up, or even a movie like Wall-E, that creates a beautiful world, but it's built slowly. You get to know and love the characters before they're in the enormous explosions.

As a result, some films make for some very tense test screenings of new movies. The studios' people are always looking around during the first 20–25 minutes of test screenings to see what viewers' reactions are. Occasionally there will be a laugh or something. But I look back at Bridge to Terabithia or even Holes, two of our highest-testing movies, it's all about "the build" in those movies. You get to know and love the characters, with a big, big payoff in the third act. They are different from films that have huge set pieces or huge chases right at the beginning.

So for us, the biggest challenge is making sure that our studio partners are patient with that type of filmmaking.

Americans just spent a year talking about health care reform. You spend your time thinking about storytelling, cinema, and audiences. What kind of "reform" is Walden interested in cultivating?

In terms of "reform" and "systematic changes" — we have to get more kids reading.

This goes beyond the fact that reading is good for people's health — it's a key part of Walden's business strategy. The fact that Bridge to Terabithia and Holes were best-selling books that already had an audience out there made it a lot easier for us to get those films made. If those were original screenplays, we could never, ever get them adapted.

But this is a problem: Walden's a company dedicated to making films based on popular books, and it didn't take us long before we had effectively run out of choices. There were plenty of options those first few years, but now the cupboard is growing pretty bare. We're out there looking. We're starting to publish our own books. So hopefully for us, we'll get to the point where the books that we're publishing become a real, solid source of material for our films.

That's why we're really hoping that to get a film going on the book Savvy.

Tell us about Savvy.

Savvy is a Newbery honor-winning book by a first time author named Ingrid Law. It's about a fascinating family — a home schooled, Christian family.

In Savvy's world, on your 13th birthday, you become aware of your "savvy." Your savvy is your unique talent that could be anything from reading people's minds to creating hurricanes to baking the perfect pie.

Mibs is the protagonist. Her father gets into an awful car accident just a couple of days before her 13th birthday, and her hope is that her savvy will be something that will help save her father.

We have a fantastic script. Karen Janszen, who wrote the script for A Walk to Remember, wrote this script for us. We're out looking for directors right now. It could kick off a new genre of home-schooled superheroes.

How does Walden choose which storytellers to embrace?

The storyteller's voice is certainly critical. And sense of humor is certainly critical.

I'm blessed with a son that reads a lot. He loves the voice that Jeff Kinney uses in Diary of a Wimpy Kid. Kinney's got a great sense of humor. He's got great characters.

It's so different for boys and for girls. We have to be more honest about that, considering the current reading crisis. We're partnering with a great children's author named Jon Scieszka, and Jon is editing a new book series for us called "Guys Read." He's written so many of my son's favorite books. It was just such a blessing to be able to work with him on this new series, along with Christopher Paul Curtis, Jeff Kinney, and Kate DiCamillo. Kate leads the way in knowing what kids really respond to.

And kids respond to a sense of brokenness, too — that sense that the world isn't as perfect as they had thought, and that things can be reconciled and made better.

Last time you spoke with Response, Walden was still fairly new to filmmaking, and you were preparing the first Narnia film. Now you're finishing up the third in the series, and you have a long list of movies you've produced. What's the hardest lesson you've learned along the way?

I think the hardest lesson we've learned is that we're in the hits business. You can go from a period where you have films that are doing great, and then you can hit a cold spell for years. So you really start to question yourself and what you're doing and reevaluate things.

That's where it's really helpful to have a mission statement be your north star.

What lesson do you hope that Hollywood is learning from your work?

There are enormously loyal audiences out there for literature, just as much as there are for kids' toys. We hope the industry is learning to consider children's literature as a branded property, no different than a comic book character or a popular television series.

The second lesson — and it's a lesson that we have to remind ourselves, because we're not batting 1,000 in this by any stretch of the imagination — is to involve authors a lot more into the screenwriting process.

What counsel do you have for aspiring filmmakers who want to make great films and make a difference?

I think they should all read The Screwtape Letters.

In this business, the greatest ethical challenges are sometimes about making bad decisions one millimeter at a time, until we find out that we're several kilometers away from where we should be. It's important to make the right decisions every single day, inch by inch, so you don't wake up one day and find you're making films that are completely different than the ones you got into the business to make, or, even worse, that you've become a totally different person.

SPU students are people who feel a real sense of mission and a real sense of purpose. These aren't kids going into film just because they think it's cool. They understand that stories have an enormous power to transform and shape culture. And I think that it's even more important for folks like the students at SPU to always be mindful of that.

Speaking of Screwtape, wasn't Walden adapting that book into a movie a while back?

Ralph Winter, who produced the X Men series, some of the Star Trek movies, and Fantastic Four gave us a crack at partnering with him on it. But speaking for me and the other Walden folks working on it, we just could not figure it out how to approach it creatively.

Does it have to be set during World War II? Does it have to be set at wartime? Does the patient have to lose his life in battle? Does there only have to be one patient, or can we track multiple patients? Does it have to be Great Britain, or could it be Los Angeles, which is a great setting. I think it's a town Screwtape would love. What shape do the demons take? Are they interacting with us personally? Or are they just sort of a whisper that's in our head that we can't identify?

These were all great questions. Each one of them can set you off into a different direction creatively. We just couldn't figure it out and we decided not to move forward.

But it's back. I think that Ralph has come much, much closer to figuring out a way to approach it. I'm confident that he will be able to do it.

We had a difficult experience with the adaptation of Prince Caspian, and got some criticism for that. We truly, perhaps naively, thought that we were making a good adaptation there. But we saw the problems with it, and so there is no way we're going to take so many liberties with Screwtape after the Prince Caspian experience.

What is your greatest hope for The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader?

My biggest hope is that when we have the test screenings, when we ask people questions afterward, they're still wiping their eyes. I think that the ending of Dawn Treader is the most emotional of all three Narnia films, and one of the more emotional endings I've ever seen in a film. Even if you don't know the books, it's such an emotional goodbye to Lucy, who's my favorite character, and Reepicheep, who's my second-favorite character. To see both of them bid their farewells, it's super emotional.

My second-biggest hope is that people love Eustace, because he's going to be a pretty important character for us moving forward.