Remembering the Future

Jürgen Moltmann’s Theology of Hope

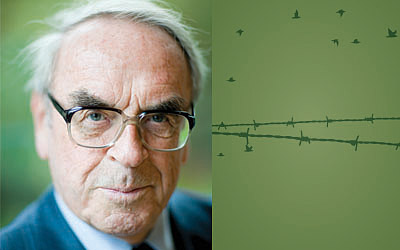

Renowned theologian Jurgen Moltmann spoke on SPU's campus for the 2007 Common Day of Learning

By Douglas Koskela, SPU Assistant Professor of Theology [kosked@spu.edu]

Photo by Daniel Sheehan

“I began to understand the assailed Christ ...

who takes the prisoners with him on his way to resurrection.

I began to summon up the courage to live again, seized by a great hope.”

—Jürgen Moltmann, The Source of Life

Amid the optimism and turbulence of the 1960s, a book by a little-known German theologian burst upon

the scene. Not only did Jürgen Moltmann’s Theology of Hope resurrect the doctrine of Christian hope in

academic theological discussion, but it also propelled its author to worldwide renown.

Theology of Hope captured the attention of the public as well as theologians — it was even lauded in a front-page

article in The New York Times: “God Is Dead Doctrine Losing Ground to ‘Theology of Hope,’” announced the headline. Clearly, Moltmann’s vision of hope connected with the spirit of the times.

Forty years later, in a world that has changed in so many ways, the impact of Theology of Hope continues to be felt.

Moltmann’s first book is taught in universities and seminaries around the world, and its ideas have dramatically shaped

our understanding of one of the most important Christian doctrines.

How do we account for the staying power of Moltmann’s vision? To begin, we might clarify just what it is he means

by hope. It would be a mistake to attribute to Moltmann the naïve belief that human ingenuity alone can heal all social

ills or overcome the power of evil and injustice. Theology of Hope is anything but a thin affirmation of the “power of

positive thinking.” Rather, Moltmann argues that we must acknowledge the suffering and injustice that mark our

experience in the world. Only then can we feel the force of — and give witness to — God’s promise to heal the world.

This understanding of Christian hope was born in perhaps the unlikeliest of places: a POW camp in the aftermath

of World War II.

Moltmann was drafted into the German army during World War II

For more photos, visit the Photography Gallery. |

The featured speaker at Seattle Pacific University’s Day

of Common Learning this fall, Jürgen Moltmann was born in 1926 in Hamburg, Germany. He grew up in an educated, secular home, reading the luminaries of literature and science. By his own account, his heroes were Albert Einstein,

Max Planck, and Werner Heisenberg. By the time he was drafted into the German army during World War II, Moltmann had had little exposure to the Bible or the resources of the Christian faith.

Toward the end of the war, Moltmann surrendered to a British soldier and was taken as a prisoner of war. With memories of terrifying battles fresh in his mind, he found that the literature which had meant so much to him as a boy was now unable to sustain him.

He became even more troubled when he and his fellow prisoners were confronted with pictures of concentration and extermination camps at Belsen and Auschwitz. The initial disbelief among the German soldiers soon gave way to a grave realization that they had indirectly participated in these horrors. As

Moltmann recounts in his book The Source of Life, “The depression over the wartime destruction and a captivity without any apparent end was exacerbated by a feeling of profound shame at having to share in this disgrace.”

At that point, many of the prisoners gave in to despair and lost any desire to look to the future. Yet Moltmann was confronted by an unexpected source of hope when a chaplain gave him a Bible. He was confused by a great deal of what he read, but he found himself transfixed as he came across the psalms of lament and the passion narrative of Jesus.

As he read about the suffering of Jesus on the cross, Moltmann writes that he was encountering a God who could identify with his own suffering. “I began to understand the assailed Christ because I felt that he understood me,” he recounts. “This was the divine brother in distress, who takes the prisoners with him on his way to resurrection. I began to summon up the courage to live again, seized by a great hope.”

This hope not only enabled Moltmann to press forward, but it also shaped the way in which he would spend the rest of his life.

Moltmann served as a pastor for a number of years before he began teaching at the University of Bonn in 1963.

For more photos, visit the Photography Gallery. |

After his release from POW camp, Moltmann pursued graduate studies in theology. He served as a pastor for a number of years before accepting a teaching post at the University of Bonn

in 1963. He moved to the University of Tübingen in 1967, where he spent the rest of his teaching career and is now professor emeritus of systematic theology. Theology of Hope was his first major book, and it aimed to account theologically for the hope that had taken hold of him in the POW camp.

As Moltmann developed his account of Christian hope,

he steered a careful course between undue optimism in

human abilities and outright despair. Recent history had shown the dangers of both extremes. The years surrounding the turn

of the 20th century had been, by and large, a time of great optimism for the Western world — and the Christianity of the

day generally reflected this confidence. However, after two devastating world wars, political and economic chaos, and the rise

of the nuclear age, this optimism gave way to stark humility by

the middle of the 20th century. From a theological perspective, the world was confronted by a renewed acquaintance with

the reality of sin.

Given his personal involvement with such tragedies,

Moltmann did not regard a cheap, thin optimism as an option. Yet because of his own experience of a God who brings fresh hope in the midst of suffering and injustice, he refused to give in to the resigned belief that the world would always be this way.

The central theme of Theology of Hope is promise. The Christian faith is lived, Moltmann argues, in witness to the promises of a God who can and will make all things right. These promises are offered most clearly in the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Moltmann recognizes that our present experience seems out of alignment with the future that God will bring to creation. When this experience tempts us to flee from the world in passive resignation, the cross reminds us that we are not alone in our suffering. Just as the young Moltmann found strength to press forward when he read about the God who encounters us on the cross, so also we are called toward a new future — even as the world is not what it should be.

Moltmann makes it clear that it is the resurrection of the crucified Jesus that ultimately grounds Christian hope. The resurrection is a powerful word of promise that stands in contradiction to our present experience of suffering and death. Yet this is not a promise that we await passively. On the contrary, we move forward in the light of hope toward the transformation of the world that God will bring. “To believe,” Moltmann writes, “means to cross in hope and anticipation the bounds that have been penetrated by the raising of the crucified.”

How, then, does Moltmann understand hope? Hope, he argues, is the active expectation that God will heal and transform the world. Hope does not mean the denial of suffering or injustice, nor does it mean that human beings are able to heal creation apart from God’s gracious empowerment. Rather, hope is based in what God has promised to do in the future, and it calls us to witness to those promises in actions of healing and justice in the present. When we are tempted to lose heart because of all we see in the present, we are called to remember the future that God has promised and press forward in hope.

Return to top

Back to Features Home

|