Can History Help Us Avoid a "Clash of Civilizations"?

By Donald Holsinger

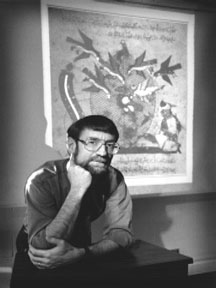

Photo by Jimi Lott

Professor of History

![]()

Born in Puerto Rico, Donald Holsinger has long been interested in other cultures. In the 1970s, this

curiosity took him to Algeria, where he taught secondary school for two years and then returned to research Muslim communities of the Sahara Desert. Years later, he traveled again to Africa, this time to Kenya and Uganda with a SPRINT (Seattle Pacific Reachout International) team.

Holsinger earned his Ph.D. in African and Middle Eastern history at Northwestern University in 1979, and came to Seattle Pacific University as a professor of history in 1990. He was chosen to be the SPU Weter Lecturer in 1997, and presented a paper titled "Livingstone, Darwin and Tocqueville on Global Frontiers: Southern Africa, Argentina and Algeria at the Birth of the Modern."

Known for his ability to clearly articulate complex historical issues, Holsinger has served as a Middle East affairs analyst for television and radio stations in Portland and Seattle. He is currently in the first year of a two-year term as a member of the "Inquiring Mind" speakers bureau sponsored by the Washington Commission for the Humanities. He has spoken to audiences across the state of Washington on topics related to Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

The Dome of the Rock on Jerusalem's Temple Mount. This Muslim shrine sits adjacent to Judaism's

holiest site,

the Western Wall, in a city cherished by all three monotheistic faiths.

An Islamic painting shows the sacrifice of Abraham, with the angel substituting a sheep for

Abraham's son. Jews and Arabs both claim descent from Abraham.

![]()

![]()

Projected behind Professor Don Holsinger is an illustration from al-Jahiz's Book of Animals, one of some 200 works by this learned man of the Islamic Golden Age. A resident of Baghdad who rose from humble origins, al-Jahiz fused Islamic natural sciences with Greek rationalism. Legend has it that he was crushed to death by a collapsing pile of books in the year 868.

Along with the end of the Cold War have come predictions that the 21st century will witness another "Clash of Civilizations," this time between Islam and the West. Imagining such a clash within the context of recent crises in the Persian Gulf generates at least as many questions as answers. American Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, in Western dress, meets with Arab Muslim leaders of the Gulf, in traditional garb, to plan strategy against their common adversary, Saddam Hussein, who normally sports a Western-style military uniform. Exactly which civilizations are clashing?

Generalizing about cultural differences is unavoidable; impulsive reactions to stereotypes can be tragic. Take, for instance, what happened in the aftermath of the April 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Muslims across the United States were targeted for persecution. Mosques were desecrated, veiled women harassed, and car windows broken. Seattle unfortunately was not spared such outbursts of bigotry and fanaticism. Recent economic turmoil in Indonesia has triggered similar eruptions of cultural chauvinism against Christians by Muslims.

Should we view such misguided acts as signs of the coming "Clash of Civilizations"? Should we fatalistically accept predictions based on myths and stereotypes? Or rather, should we thoughtfully examine the past to seek the roots of present-day predicaments, recognizing that arrogant predictions can turn into self-fulfilling prophecies?

![]()

Distorted Images

For many Westerners, the words "Islam," "Middle East" and "Arabs" trigger frightening and repulsive images of fanaticism, terrorism, corruption, cruelty and lechery. A recent Showtime movie, Escape: Human Cargo, is just one more deplorable illustration of Hollywood's favorite villains: Arab Muslims from the Middle East. Many years ago I was dismayed to discover that a cartoon feature on The Electric Company, a popular "educational" program that was shaping my children's young minds, always pictured the villain as a man in a turban and gown, sporting a goatee.

Sand, camels, harems, oil and terrorism - these are as remote from the daily life of Muslims around the world as from the lives of typical Americans. Yet they are ingrained in our Western imaginations at an early age, just as many people in the Middle East and other parts of the Muslim world grow up with distorted images of the West.

So where do we start when trying to separate truth and myth? The following "quiz" is usually an eye-opener: Of the seven countries of the world with the largest Muslim populations, how many are Arab and how many are located in the Middle East? The answers: None of the seven (Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Iran, Turkey, Nigeria) is Arab, and only two (Iran and Turkey) are in the Middle East. And yet these three "worlds" - Islam, the Middle East, Arabs - are often lumped together in our minds as if they were one and the same, a negative muddle of images.

This is not to deny the historical and contemporary significance of the Middle East; Muslims do turn toward Mecca five times a day to pray and several million pilgrims gather at Mecca for the hajj each year. But the diversity within the Islamic world is wider than most people think.

What is more, the common ground shared by the three monotheistic faiths - Judaism, Christianity and Islam - is much greater than generally acknowledged. All three arose in that remarkable region, the Middle East, which has served for millennia as both cradle and crossroads of civilizations.

![]()

Home of Ancient Civilizations

When our American military forces are deployed in the Persian Gulf, they are returning to the very source of our Western civilization. By the time that Judaism, the oldest of the three monotheistic faiths, took form in the second millennium before Christ, the Middle East was already a land of ancient civilizations. Southern Iraq, home of ancient Sumer, gave the world the first cities, the first astronomy, the first wheel, the first maps, the first schools, and the first writing.

The ancient civilization of Sumer eventually collapsed, and the desolate mounds of southern Iraq still stand as mute testaments to the dangers of over-exploiting a fragile environment. According to traditions shared by nearly half the world's population, Abraham, son of an idol-maker, emigrated from the collapsing civilization of Mesopotamia and settled in Palestine, called "the Holy Land" by Jews, Christians and Muslims.

Centuries later, following the rise of Islam, Iraq once again emerged as the center of a grand urban civilization. Toward the end of the first millennium A.D., Baghdad grew into a thriving metropolis of the Islamic Golden Age, capital of a civilization stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific. This civilization not only passed on to Western Europe the intellectual traditions of the ancient world, but gave us algebra, algorithms, optics, experimental medicine, hospitals, universities and guitars.

Paradoxically, the civilization of Islam, which incorporated elements of Greek culture and which contributed to the development of modern Western civilization, became the foil against which Western Christendom defined itself. It's as if a Cold War (sprinkled with hot phases) between Christendom, based in Western Europe, and Islamdom, based in the Middle East, lasted for thirty times as long as the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

![]()

Centuries of Conflict

Shifting thrusts of military power between the two regions over fourteen centuries created layer upon layer of negative imagery that became deeply imbedded in the language, literature and folk traditions of both civilizations.

Let's take a quick historical tour:

- The rapid westward military expansion from western Arabia following the life of Muhammad in the seventh and eighth centuries brought much of the Mediterranean region, including Spain and parts of France, under Arab-Muslim control, planting seeds of fear and hostility between Western Christendom and Islamdom during the formative stages of both civilizations.

- The European Crusades from the late 11th to the late 13th centuries reversed the momentum of expansion, bringing parts of the Holy Land under Crusader control, etching deeper the antagonistic images on both sides.

- The formidable assertion of Ottoman Turkish power westward across the southern Mediterranean and into the heart of central Europe from the 14th to 16th centuries reversed once again the momentum of expansion between the two civilizations, fostering genuine fears that Western Christendom would be overrun by the forces of Turkish Islam.

- The age of European imperialism from the late 18th century to the mid-20th century placed most of the Muslim world under European domination, due to the tools of the industrial age, leaving a legacy of humiliation still deeply felt.

- The 20th century struggle of competing nationalisms over Palestine culminated fifty years ago this spring with the creation of the state of Israel, which became in large measure the Western window on the Middle East. Israeli perceptions of the Islamic Middle East, and the Arab world in particular, as aggressive and intolerant, further reinforced older Western stereotypes.

- Beginning in the 1970s, the resurgence of traditionalist Islamist movements, especially the Khomeini-led revolution that overthrew the American-allied Shah of Iran, reconfirmed negative Western notions of Muslim piety.

![]()

Breaking the Cycle

It's little wonder that after almost 1400 years, mutual stereotyping and cultural conflict continue to be recycled, erupting at times into violence as people lash out at hateful and threatening images. "An eye for an eye" - and the whole world goes blind.

The study of history helps us to lighten the cultural baggage that has often poisoned relationships between two civilizations. An honest and balanced study of the past means we no longer have to passively accept distorted legacies. Rarely do Christians and Muslims realize how much they have in common, not the least of which are a respect for individual free will and a vision of social justice based on divine revelation.

To be sure, there are fundamental doctrinal differences that should not be minimized, above all concerning the nature of Jesus. Nevertheless, what adherents of both faiths have paradoxically overlooked through the centuries is the following: Jesus, revered by Muslims as a voice (prophet) of God and by Christians as the face (Son and Incarnation) of God, instructed his followers to break the cycles of revenge so ingrained in human nature: "You have heard that it was said, 'Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth.' But I tell you . . . If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also. . . ."

Will the 21st century witness a great "Clash of Civilizations" between the Islamic world and the Western world as some predict? Or will it be a century of shalom, a Hebrew word almost identical to its Arabic sister word salaam meaning "peace," and from which the word Islam is derived? The answer may well hinge on the extent to which both Christians and Muslims heed the message brought by a baby born two thousand years ago, a baby whose miraculous birth is affirmed by both faiths.

![]()

Please read our disclaimer.

Send any questions, comments or correspondence about Response to

jgilnett@spu.edu

|