2:The City and the Inner City

American cities grew in response to economic forces rather than through rational urban planning. They tended to shoot up where natural resources such as waterways and raw materials made industrial expansion most attractive. Early opportunities for unskilled labor brought floods of immigrants into the rapidly growing American cities. Cities continued to grow because they became centers of industry, transportation, and communication. In short, they became the nerve centers of society. Cultural refinements-art, drama, music, and literature-followed after the urban seeds, as Donald Benedict says, had shot well out of the ground.1

Today American cities are declining in response to changing economic forces. Industrial cities of the North are no longer thriving, and the explosive growth in the Sun Belt seems to be slowing.

Problems of poverty and unemployment are on the rise. One out of every six American families is on welfare, with one of three on the brink. Many of these indigent people are located in urban squalor.2

DECLINE OF THE CITY

Carl Dudley sees social decline and transition in the city as the result of pulls and pushes in the American economy. More spacious and desirable opportunities open up in the suburbs or urban fringes, and the affluent head in that direction, while a poor class of urbanites pushes into the vacant area. There is an ongoing process of exit and entry such that neighborhood and community transition is simply an urban fact of life.3

Jim Newton describes the overall transition process within a community as taking place in five stages: (1) the construction of single- and multiple-family dwellings; (2) a stable and homogeneous resident population; (3) a pretransition phase with a socially different group moving in-this group need not constitute even 10 percent of the community's population; (4) a transition stage during which the new group comes to represent from 10 to 50 percent of the population; (5) the posttransition stage when the new group becomes the majority.4

The process of recent urban deterioration follows a pattern. As the affluent move out, businesses head for suburban developments and malls. The absence of businesses and a strong middle class erodes the tax base so that, without governmental aid, cities head for bank�ruptcy. Although some urbanologists detect some movement back to the city because of high energy costs in commuting and the desirability of "rehabbing" older dwellings, this trend does not suggest socio�economic integration. If anything, economic segregation looks to become more stark as affluent communities create walled sub-cities around themselves amid the hungry slum dwellers.

In addition to the erosion of the tax

base caused by the exodus of the affluent and businesses, the tax structure

itself kills urban commu�nities. In

In the same spirit as Campolo, the outspoken Michael Har�rington, in The Other America, claims that what we have is socialism for the rich and free enterprise for the poor.6 By this he means that whereas middle-class Americans regularly complain about "social�ist" welfare programs for slum dwellers, the fact is that the more affluent receive the thumping majority of the tax dollars. That the poor receive very little can be observed in how much of each tax dollar goes into highway construction, higher-education facilities, salaries of governmental employees, and maintenance and renovation of parks and other recreational facilities used by the larger society. Although some argue that the middle class should receive more tax benefits because they pay the preponderance of the taxes, the point is that they do.

In fact, political pressure from power

brokers is such that it is almost impossible to get legislation that will

deliver benefits to the needy without skimming the cream for the rich. In

In addition to erosion of the city's tax base and unjust allocation of tax benefits, the city's finances are affected by the fact that earnings are taken out of the city by many suburbanites who make their living in the city. They drive in on public expressways and city streets that are paid for by city taxes, drink city water, flush city toilets, and walk city pavements, but they pay taxes and acquire goods and services in a suburban municipality. All the while the poor remain in a colony of misery, walled in by poverty and a lack of opportunity.

F. K. Plous,

Jr., claims that 85 percent of urban decline can be traced back to three pieces

of legislation.7 The first was the Home�owner

Loan Act of

The second piece of legislation was the

Serviceman's Readjustment Act of

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of

With suburban growth and urban decline, Pious says that the middle class "smelling the meat acookin' elsewhere, wisely left, and refugees from rural poverty and Southern discrimination flowed in to occupy what was already abandoned territory." 8

EMERGENCE OF THE INNER CITY

According to Ed Marciniak, the city can be studied as an urban layer cake.9 The first layer consists of family-associated people. Layer two involves the neighborhood. The third layer is the larger community: the police, the fire district, the school district, the political division or ward, library, local newspaper, citizens' organizations, and perhaps a Kiwanis association. Beyond the community level is the city as a whole. These layers are interdependent: if any one layer does not function, the whole cake will ultimately collapse. The first two, however, are probably the most important, for they form the foundation.

Marciniak argues that cities never have worked; they are in constant transition and restructuring. In fact, the great cities tend to be rebuilt every one hundred or one hundred fifty years. What can work are the neighborhoods. When they decay, inner cities emerge and the city at large becomes shaky. Vitality is at the micro rather than the macro level.10 This topic is discussed at length in the next chapter.

Characteristics of the Inner City

Since the inner city is the major focus of this book, the concept requires definition. The inner city does not necessarily refer to the geographic center of the city. In fact, it is probably more accurate, when describing a given city, to speak of its several inner cities. An inner city can be defined as a poverty area in which there is much government activity and control but little activity by the private sector. Often, merchandisers, businesses, and churches have left the area. The usual urban amenities, such as dry cleaners, barber shop, camera store, appliance shop, and the like, are in limited supply. But govern�mental agencies, public housing, and social institutions are visible. Private institutions of this type-both for-profit and not-for-profit�-are absent.11

Besides "poverty area," there are a number of other synonyms for the inner city: low-income community, central city, or ghetto. Although technically referring only to a place of isolation, the term ghetto has come to suggest a predominantly black community. Inner cities are not always black. They can be inhabited by almost any racial or ethnic group. Blackness is common because blacks are the most urbanized of all ethnic groups and a sizable proportion (about one-�third) are trapped in poverty.

Regardless of ethnic makeup, the inner city can often be charac�terized as "the other world." It is the other side of the American fence, opposite the side on which grass is green. A black college student once wrote a term paper for one of my classes in which she described that other-world feeling she had had when she was younger. The young, black, inner-city child, she wrote, feels that he must live in the worst place in the entire world, for nothing that goes on in school or his textbooks, from reading class to geography, is in any way related to life in the community in which he lives.

Almost invariably inner cities, by

Overcrowdedness can have nerve-shattering consequences, es�pecially for people with rural roots. Misery and degradation are packed together. Experiments with laboratory animals indicate that when rats are confined to an overpopulated space, they begin killing each other off until their numbers reach manageable size. Social scientists continue to debate the likely human implications of these types of findings.12

At any rate, building is lined up against building, or in the case of high-rises. floor is stacked upon floor as the misery heads skyward. With exploding numbers comes limited space, limited privacy, and the omnipresence of noise from voices, stereos, cars, and people themselves. Eight may live in a three-room apartment. "Go to your room" is a disciplinary statement that would be simply preposterous to an inner-city child.

Overcrowdedness, of course, points to as critical a physical characteristic of an inner city as any-inadequate housing. Quality housing in the inner city is in such small supply that the 1960s saw the emergence of a new cabinet department-Housing and Urban Devel�opment. The poor are, by virtue of their poverty, herded into central city communities where land and, more particularly, housing are at an absolute premium. Where housing does exist, the buildings are old and crumbling. A ride through an inner-city area invariably reveals this phenomenon to the curious onlooker, who will see either ancient and deteriorated or gutted and burned out buildings.

The only other housing available is public housing such as the federally sponsored high-rises�high-rises because limited space de�mands vertical rather than horizontal construction. One of the prob�lems contributing to the decay of the inner city is that the poor do not own property. The welfare system allows recipients to rent dwellings but not buy them. To qualify for low-cost housing a person must not earn in excess of a given, rather paltry amount (often about $8,000 annually). This works against the care of property that results from pride of ownership.13

While the rest of society laments the absence of moderately priced housing and reasonably sized lots on the urban fringes and in the suburbs, the poor look for shelter of any kind.

Causes of Inner-City Conditions

A number of causes contribute to the conditions of overcrowdedness and inadequate housing in the inner city. The first cause is the transition from a stable neighborhood to a changing neighborhood. As people move away, vacant housing develops, followed by entry of people socially different from the dominant residential group. The more different the incoming group is, the quicker the residents flee. Hence, stability is gone. No one is certain when the "tipping point" in any community will occur, but when it does, the community quickly turns over. Some realtors unscrupulously come in and prey on the fears and stereotypes of the anxious residents. They may plant fears of plunging real-estate values and imminent violence in order to buy up resident housing cheaply, only to turn around and sell that same housing to incoming residents at a booming profit. This practice is called blockbusting, and though grossly unethical, it is very common.14

The second cause is fiscal dysfunction. Many neighborhood functions reflect personal income, which in part is turned into taxes to maintain semipublic enterprises such as schools, libraries, public offices, and hospitals. As income accumulates, the residents put it into banks and savings and loan associations. In turn, these financial institutions lend money in the form of credit to neighborhood residents to enable the community to grow and develop. If, however, the demand for housing decreases in the neighborhood, trouble ensues. Since the housing supply is fixed, this dip will drop prices, which will alarm financial institutions and cause them to cut back on loans. This cutback is called redlining.15

Redlining begins with bank officials outlining an area that they feel will decline over the next twenty years (the length of many mortgages). As a result of this prediction, the bank chooses not to lend any mortgage money to anyone wishing to purchase land in the redlined area. Though illegal, this practice is used to protect the bank against high-risk lending. What is happening, however, is that the bank, ostensibly a servant of the community, becomes its killer. People who desire to purchase in the inner city and then rehabilitate the dwelling are summarily ruled out of such an enterprise, while current owners become increasingly aware that they are literally stuck with unsellable property. This encourages management toward demolition.

The result of these practices is that the inner city takes on the appearance of a ghost town as the area becomes dotted with burned�-out, abandoned buildings, surrounded by open space. In spite of inadequate housing and this available land, there is no building going on. In every case the community and its residents lose because the bank, by virtue of redlining, has made its prophecy of community doom self-fulfilling.

A study of the redlining practices of a

savings and loan associa�tion in

In stable communities, with deposits

going into banks and with loans coming out, a dollar will turn around about

seventeen times.18 In a redlined area,

however, the money flows steadily out, with the neighborhood financial

institution sending the money to larger down�town banks. In the meantime,

nothing is built or developed, and the community deteriorates. Such a shipping

out is evident in a

City money is flowing to the suburbs.

The

The importance of investment in a community cannot be over�estimated. William Ipema points out that in Chicago, for example, thirty-six of its seventy-six communities are nearly dysfunctional fiscally. With community fiscal health much determined by green flow-credit and capital funding-some of these communities are dying, as less than one percent of savings money is making its way back into the community in the form of loans.21

In addition to the conditions created by blockbusting and redlin�ing, there is also the problem of slum landlording. An owner of a dilapidated dwelling will manage it toward demolition. The first step is to fill the building with as many "rents" as possible. Rents are then received without any attempt to keep the building in repair. The aged nature of the building, coupled with its heavy usage by children and young adults, results in rapid deterioration. City inspectors, whose task it is to check the quality of urban structures and insure that they are "up to code," are easily bribed into not reporting housing-code violations. The inspector's conscience is assuaged because he feels that the city grossly underpays him and that reporting building vio�lations will simply set off a lengthy legal procedure, sometimes as long as four years, which will likely end with either the landlord minimally repairing the building or abandoning it entirely and leaving the people shelterless.

One of the reasons the owner does not make repairs is to keep overhead and real estate taxes at a base level. Rents are picked up until the building is so badly worn that it either begins to collapse or the city demands repair. At that point the building is often "torched"��burned to the ground. The torching marks the end of both the structure and the legal problem of the owner, who will probably collect fire insurance money since that is one premium he will keep paid. Torch�ings often occur with the inhabitants still in the building, destroying much of their goods as well as imperiling their safety. Such fires appear more accidental and raise less suspicion. They are extremely common, however. During 1974, for example, there were fourteen thousand fires in the South Bronx.22 In urban areas nationwide, literally thousands of such torchings of buildings occur in old white, black, and Hispanic sections.

In addition to failure to repair buildings, slum landlords neglect utility needs of the renters. A not uncommon practice is to fail to heat a building in the dead of winter. So prevalent is this problem that city television stations regularly flash the city hall telephone number where help can be obtained. Colds, influenza, pneumonia, and frost�bite are common health problems in inner-city winters. From the standpoint of the slum landlord, who is aware that the court process is slow and few poor city dwellers have any knowledge of it, ignoring the needs of a building is a low-risk, high-profit enterprise.

Blockbusting, redlining, and slum landlording are outgrowths of greed and prejudice. This greed and prejudice will almost certainly be felt by the pastor who truly desires to minister to an urban neighbor�hood. As such, it is of utmost importance that he learn as much as possible about the institutional policies and processes attendant to high density.

THE RESPONSE OF THE CHURCH

Churches in the city have had to respond to both the decline of the city and the emergence of inner-city areas. Some churches, as Carl Dudley points out, pass through several stages as they respond to their changing community, eventually relocating or closing. Other churches, however, have sought ways to revitalize the community by dealing with conditions of inadequate housing, fiscal dysfunction, and government control.

The Church in Transition

Although churches and denominations

like to affirm integration and may even assert that a minority group would be

welcome to take over a church if it becomes dominant in the neighborhood,

churches do not usually respond that way.

After initially "going indoors" to reaffirm what is really left of their notion of community culture, a congregation discovers that some of their families have moved out of the neighborhood. The usual reaction to this is regionalism-attempting to keep these families in the church by making the church a metropolitan rather than a neigh�borhood enterprise. They seek to affirm their initial culture while in a psychological state of denial.

This usually collapses after funds are drained and the exhausted pastor leaves. Expansion thus gives way to contraction. A smaller church admits it is undergoing changes but is determined to prevail. There is increased giving and activity as the parishioners, rather than simply the pastor, become the church. Spiritual faith increases in this phase and there is a sense of genuine zeal. Stresses do build, however, and on occasion people will explode for seemingly inexplicable rea�sons, leaving the church. There is much suppressed anger in this response as the church attempts to manage its way through the transition.

When the church runs out of money, the

accommodation stage emerges. The church expands its outlook, seeking to perform

minis�tries in the changing community and being willing to share whatever

resources they have with other groups in order to raise money. Church buildings

will be rented out, federal monies sought, the pastor allowed to work in a

secular job on the side, and so on. Bargaining character�izes this stage as the

church lives in tension. Interestingly, Bill Leslie of

The accommodation phase ends with the younger, upwardly mobile families moving out and leaving the older parishioners behind. The resultant phase is one of grief. The grieving period gives way to death. The church may fade gradually by reducing its activity or it may relocate. Regardless of the style, it is in its last phase.

On occasion, out of the contraction stage evolves a new type of church-one dominated by an ethnic or racial minority group with a faith expression congruent with its nationality. The whites in these churches find it alien, however, for their formative experience with God is not rooted in Spanish or some other non-Anglo pattern.

In 1979

Revitalizing the Community

The church that chooses to be involved in revitalizing the community must seek creative answers to the problems of inadequate housing and fiscal dysfunction. These answers may include such ideas as sponsor�ing rehabilitation organizations, offering courses in building mainte�nance, founding banks, using investment portfolios judiciously, and working with community and governmental agencies. There are a number of examples from around the country.

Before a church becomes involved in

dealing with the issue of inadequate housing and the practices of redlining and

slum landlord�ing, it would be good to do some

necessary research into local community housing. Alderman Richard Mell suggests ten check�points.25 Many of these issues can be checked out at a knowledgeable

social agency. The social service agencies are all listed in the Social Service

Directory available from the

1. Determine which way credit or money flows in community institutions. Does the money come from the residents, go into commu�nity institutions, and then flow out of the community? Or do these institutions reinvest the money to developing a stronger community? What about redlining by banks or insurance companies?

2. Check into institutions outside the community. Which ones are sensitive to inner-city needs and which are notorious for exploitation?

3. Find out who owns the community property. Is it privately owned? Slum landlorded? Government sponsored? How dense is the area? If there are vacancies, find out why.

4. What is the condition of the buildings? Why are they in that condition?

5. What kinds of aids are available in the public sector for housing development?

6. Have there been any redevelopment attempts? What aids for rehabbing are available?

7. What are the going tax rates? Is there massive tax delinquency and corruption?

8. What community organizations are concerned about housing?

9. Are there industrial and commercial job opportunities? If there are, they show evidence of concern for the community because these entities have a vested interest in their location. If there are not, the community has become more blighted.

10. What is the future of housing in the community? Is the area becoming less residential or more so? Does the community have plans for the area?

Once armed with the answers to these questions, the church can proceed with greater confidence. There are a variety of responses churches can make. A church should look first at what social agencies may be doing in the community before embarking on some costly, alienating, overlapping effort.26 Knowledge of such simple matters as key helping institutions in the community, city agency phone num�bers, and other urban areas where housing can be obtained at low cost can be very helpful to confused residents who do not know which way to turn.

To effect change in a community it is necessary to organize. Without organization there can be no coherent voice. It is important also to find local, indigenous leadership and build from that base. The revitalization of an inner city requires partnerships, alliances, and coalitions rather than just money. Coalitions are important because of the interconnectedness of the community involved. Once there is a concerned and articulate community force, there can be effective negotiation with city hall. Moreover, it is crucial that positive rela�tions are maintained with government at all levels. Despite the fact that the government may sometimes be the adversary, without cordial relations little progress can be made.27

Ipema has some ingenious suggestions about how to work with, rather than against, social agencies.28 First it is important that they be approached in a positive way. A climate of cooperation is very helpful. To have maximum effect, however, it is important that the church know the mechanics of a given agency, i.e., what services the agency offers, how one makes application, and what procedures the organization follows.

Ipema suggests that a pastor develop a relationship with a middle-level official. Lower-level officials may provide unsatisfacto�ry service, while upper-level officials may be enmeshed in the bureau�cracy. In initiating a relationship, it is very helpful to begin by asking how the church may be able to help the agency. An enterprising pastor can identify needs and problems that his parishioners can help to solve. Such a cooperative approach opens doors and builds relationships.

Philip Amerson suggests that churches consider taking advan�tage of available consultation services. Such services can help set a focus, discover resources, and develop a workable plan aimed at reaching important and realistic goals.29 Ipema cites three such organizations that can aid community development efforts: the National Training and Information Center, which helps community organiza�tion; the Center for Neighborhood Technology, which solicits federal research and development dollars for urban use in addition to stimulat�ing community self-help activities; and the Center for Community Change Consultants, which is also involved in self-help efforts.30

Stanley Hallett

also presents some ways of impacting on "the system." For example,

the federal government spends billions of dollars on research and development.

Church and community groups could begin to discuss how to put pressure on this

part of the federal budget. In

A pastor is wise also to get involved in his local community organizations. These alliances can be powerful forces in combating everything from pollution to prostitution, redlining to residential neglect. Such involvement is risky because the issues are controver�sial. However, community organizations by their nature are nonpar�tisan and people-oriented. According to P. David Finks, community leaders are open to contemporary theologians who will grapple with and act on problems affecting community. A conference of the Oak�land Community Organizations, a coalition of 150 neighborhood alliances affirmed this. Moreover, if a pastor is genuinely interested and helpful, he may find himself serving on a community organiza�tion's board of directors where he can have a real impact at the policy level.32

If a church's research into housing

conditions and community housing uncovers redlining practices, it would be

helpful to join with other ministers in the neighborhood and approach the local

lending institutions on the matter. In

In

In

A group of churches in

Hallett urges churches to reassess their portfolios. If they are doing business with financial institutions that are less than sensitive and concerned about the community, pressure can and should be brought to bear on them. In addition, churches can organize neighbor�hood groups to confront lending institutions concerning their commu�nity responsibility. If credit is not being extended, the people can demand data justifying the nonlending policy. Often no such data exists; decisions are made ad hoc on the basis of racial or socio�economic bias.36

Vincent Quayle encourages individual churches as well as de�nominations to take an advocacy stance on behalf of low-income victims of housing shortages and to affirm that position through portfolio investments in Christian nonprofit housing efforts or private lending institutions that will agree to extend low-interest housing loans.37 In this same line, John Perkins suggests that public housing become cooperative housing. The inhabitants would be given a deed and the opportunity of paying in equity. The interest rate could be one percent over the first five years, 2 percent during the next five, and 5 percent after that. This would yield immediate equity and, of course, pride of ownership.38

There is no limit to what a visionary,

stewardship-oriented church can do. The

In 1979,

In

In

The St. Ambrose parish in

Conclusion

These are some of the many ways an enterprising congregation can be instrumental in revitalizing the community. As the church responds with creative approaches, the problems of inadequate housing, red�lining, torching, burned-out areas, freezing conditions in winter, and the like can be met. The church can have a part in encouraging financial institutions and private enterprises to invest in the commu�nity. Most of all, the church can weather the transitional stages and continue to minister in a changing city.

The effectiveness of these approaches is greatly enhanced when the pastor and as many members of the congregation as possible live in the community. Although such a residential commitment to turf is not always possible because of family, safety, or other important consid�erations, it is a powerful statement in the eyes of the community itself.

3: Urban

Stratification and the

Stratification refers to the arrangement of a society into a hierarchy of layers that are unequal in power, possessions, prestige, and life satisfactions. More importantly, however, stratification provides un�equal opportunities to accrue the most necessary and desirable com�modities of earthly existence. It always generates differences in life�styles, or living patterns. In short, stratification separates groups of people.

Stratification within cities is often related to regional boundaries. One of the more common conceptualizations of this stratification involves the use of the concentric-zone model of urban areas.1

The central zone contains the business district where civic, commercial, and governmental functions take place. Next comes the transition zone that includes the slum neighborhoods. Oddly enough, the land here is very valuable because of its proximity to the business district. However, because the buildings are aged and in decline, much work is necessary to make the area suitable for the expanding industrialists. The next zone contains working-class homes. In this area live people whose parents were able to escape the transition zone. The fourth region is a residential zone containing single-family dwellings and apartment hotels. On the border is a commuter zone in which people seeking more desirable living spaces reside.

The socioeconomic status of the residents generally rises further from the center of the city. Communities are more stable and organ�ized, street crime is less frequent, and the quality of education and city services improves. Hence, upward social mobility means outward geographical mobility.

Understanding the larger or macro American stratification sys�tem, especially as it applies to the city, is of paramount importance in coming to terms with the dynamics of the more immediate micro system-the neighborhood. The bulk of this chapter is devoted to discussion of the larger system. This is then applied to the neighbor�hood and, more specifically, to the neighborhood church.

STRATIFICATION AND SOCIAL CLASS

The purpose or function of stratification, according to Kingsley Davis and Wilbert Moore, is to motivate individuals through the induce�ments of wealth, prestige, and power to assume positions that the society deems important and that require much talent.2 An example of such a position is that of physician. Being a physician requires considerable talent. Because physicians deal with the critical issues of defining and treating health disorders, the position is of great import to the society. Hence, being a physician is lucrative. Entertainers and professional athletes are similarly rewarded because what they do requires a good deal of talent and the society, having more and more leisure time, demands to be entertained.

The Bases of Stratification

The primary bases of stratification are

occupation, income, and edu�cation, with occupation being by far the most

important. When sociologists determine position in the social structure, they

often use these three as the criteria for placement. Occupation is especially

important because in

Joseph Kahl presented a more expanded view of the bases of stratification, listing seven major dimensions that underlie the Ameri�can stratification system.4

1. Prestige. Some members in the society are granted more respect and deference than others.

2. Occupation. Occupations differ in prestige, importance to the society, or rewards associated with them.

3. Possessions. This dimension refers to the varying amounts of property, wealth, and income.

4. Social Interaction. Different classes develop different patterns of interaction, and because people tend to associate with others at their same level, these patterns markedly separate the classes.

5. Class Consciousness. People are very aware of a social structure and their status in it, hence reinforcing its importance.

6. Value Orientations. There is evidence that different social classes have somewhat different value systems, which in turn moti�vate them to seek different lifestyles.

7. Power. Power is differentially distributed and those at the top of the social structure have greater leverage in controlling and directing the actions of others than those below them. Indeed, this power differential is as important as any criterion, for it not only refers to the ability to control the flow of wealth and political advantage, but also the ability to maintain an unequal status quo.

Stratification and Societal Dysfunctions

Sociologically, stratification has certain societal dysfunctions. Four in particular stand out. First, because people are born into a given stratum, they do not have equal opportunities at birth. As a result, the full spectrum of society's talent is not discovered. Where one is slotted into the stratification system at birth has very real consequences for the size of one's family, the amount of interaction with one's parents, and the amount and quality of education one is likely to receive. If there were true equality of opportunity, it is altogether possible that a cure for cancer might have been discovered by now-or a host of other achievements might have occurred earlier. However, the poor are all but lost to society as a result of various factors: the poor quality of education they receive, higher rates of infant mortality, motivation undercut by the anguishes of poverty. A large sector is unable to tribute to the society.

Second, because of gross inequities in reward distribution, there is a lack of unity in the society. When some receive better health care, education, police and fire protection, and so on, there is bound to be discord and unhappiness over these inequities. The society disintegrates into interest groups, factions, and other divisions. These further divide the society and weaken it.

Third, with some in the society being

granted greater deference and respect than others, loyalty to the society is

destroyed. "Who you are" and "who you know" are very

important in

Fourth, stratification affects self-image, which in turn is related to creative development. This issue is of special significance for children. Children who grow up well fed, respected, and loved, and who attend schools in which students are made to feel important and valued, develop more positive self-concepts than children who realize that they are not deemed of much worth in the society. The result, more often than not, is that those who are made to feel positive are more likely to actualize their potential and develop their skills than those who feel they are not of much worth and who are discouraged from feeling they have anything to contribute. Where creativity and industriousness are depressed, the society suffers from a loss in its collective reservoir of talent.

These are but four of stratification's dysfunctions. It should be noted that they are societal; in other words, they hurt society as a whole. Some individuals may benefit from these societal dysfunc�tions, for they are advantaged by others' disadvantages; however, the society as a whole is still the victim.

It is interesting to note that the very terms used to describe the American class system-upper, middle, and lower-convey subtle notions of superiority and inferiority that may also be dysfunctional to the well-being of the society as a whole.

The Social Class System

The American social class system can be analyzed in a variety of ways. Some simply posit an upper, middle, and lower class. Others add what is called working, or blue-collar, class, sandwiched between the middle and lower classes. A more detailed approach cuts the social structure into six sectors-upper-upper, lower-upper, upper-middle, lower-middle, upper-lower, and lower-lower. What follows is a rather brief outline of the six social classes. For the urban pastor, who may find himself working primarily with the last two groups, knowledge of the structure as a whole can be valuable in understanding the social context in which his parishioners live.

Upper-Upper Class. Often referred to as "old money," these people are those who have possessed truly super riches over a number of generations. They are usually identified by family rather than as individuals. The Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, and Mellons would fall into this group. These people keep very much to themselves and associate within their own circles. Their elitism is protected and perpetuated by the tendency to marry within their own stratum.

Lower-Upper Class. Often called "new money," this group differs from those in the higher status primarily in the length of time the wealth and prestige have been in the family.

In general, relatively little is known about the upper classes because they have a thirst for privacy and so escape the usual data�-gathering efforts by sociologists. Moreover, most sociologists are middle class and so are not conversant with the lifestyle of the elite. However, certain traits characterize the upper classes in general, and the upper-upper class in particular. Family reputation is very important. The upper class is identified by families and it is the family name that must be advanced and protected at all costs. Individual members of the upper class gain social standing by virtue of their family background and so are socialized to make family reputation a platter of high priority.

Expenditures are often made to magnify and elevate the family name. Many upper-class families, for example, have foundations bearing the family name, and upper-class individuals frequently lend themselves (and their names) as chairpersons of charity drives and socially respectable fund-raising efforts.

Women are very influential in social matters. Upper-class females are often pursued by the fashion media, are the subjects of newspaper features, and often become social trendsetters. The upper�-class people are often referred to as "society," largely because of their social prestige.

Perhaps most important of all is that the upper class is truly super rich. Their wealth is tied up in the major American industries and business enterprises, and hence, whenever the wheels of American commerce are turning, these people are making money. As long as capitalism survives, these people survive.

Upper-Middle Class. The upper classes constitute roughly 2 per�cent of the society, while the upper-middle includes about 8 percent. The upper-middle class consists of the upper and middle levels of business and management in addition to the major professions. Repu�tationally, they are viewed as "highly respectable," not because they are actually more moral than other classes, but because their moral values are the most dominant in the society and their thirst for respectability is probably the most intense among the strata.

It is the upper-middle class that takes the lead in civic affairs, including public education. In fact, it could be said that whereas the upper classes own and control the major corporations and institutions, the upper-middle class tends them on a day-to-day basis from admin�istrative and executive posts. Because of this institutional dominance of the upper-middle class, it is imperative that those who wish to succeed in the American mainstream be able to communicate with members of this class. For that reason, it is the upper-middle class clothing style and social demeanor that is taught as "proper" in most public schools.

Lower-Middle Class. These "good common people" comprise about 30 percent of the American society. They come from the ranks of small businesspeople, clerical workers, and low-level white-collar workers. These people are often rather conservative politically out of a desire to hold on to their middle-class status. They conduct their lives in a very ordered, patriotic, respectable, and self-improving fashion.

Upper-Lower Class. The largest of the social classes at 40 percent, this group is often difficult to distinguish from the lower-�middle class. Their values and lifestyle are very middle class out of a desire to be viewed as middle rather than lower class. Considered "respectable," this sector includes skilled and semi-skilled (blue collar) workers as well as small tradesmen. Moreover, policemen and firemen are often placed in this group. They often live in less desirable but non-slum urban neighborhoods, and they strive for a reputation of respectability. Male chauvinism is often rather overt here, with a tendency for women to remain subordinate.

Economic status is not very important in identifying the upper-lower class, for in many cases their annual income will equal or exceed that of the lower-middle and even upper-middle classes. The differences lie mainly in how they earn their money. They usually are paid by the hour and hence experience affluence through overtime and second jobs. Their economic status is rather tightly tied to the national economy; therefore, in boom times employment and money are plen�tiful, while during a period of recession their lifestyle can become rather austere.

The upper-lower class is often rather unsympathetic toward the poor, in part because of their wish to be associated with the middle rather than the lower class. There is also a rather strong "I fight poverty, I work" doctrine operative in this group. Frequently, they will oppose public aid of almost any sort, as they feel its funding is coming from their hard-earned, blue-collar income. In short, although they are socioeconomically closest to the poor, attitudinally they are at a considerable distance.

Lower-Lower Class. This group-the poor, about 20 percent of the society-suffers from a negative reputation in the eyes of the rest of the society; they are often viewed as opposites of good, middle�-American virtues. Probably the most painful aspect of being poor is the psychological assault it carries. The poor are considered the least worthy in a capitalistic system. They are viewed as takers rather than givers, burdens rather than blessings, contemptible and dirty rather than respectable and clean. The process of receiving public assistance is particularly humiliating.

The lower-lower class includes

unskilled laborers with sporadic and unstable jobs, poor farm workers

(especially those in the southern portion of the

When white Americans think of a lower-lower class person, there is a tendency to conjure up the image of a black face. Such a notion is false; the largest number of those in this class are white (although poverty strikes nonwhites harder by percentage).5 In fact, this class is made of many disparate groups. Every ethnic, age, and religious group has representatives in the lower-lower class.

Poverty is most apparent in the cities. As more and more affluent whites leave the city limits in quest of a comfortable suburban lifestyle �they are either not replaced, causing city populations to dwin�dle or their place is taken by poor people, whether they be Mexican-American migrants, Puerto Ricans in search of better job oppor�tunities, blacks from the South, or white European immigrants.

Some sociologists include among the poor all those in the lower fifth of the income distribution. Others use less arbitrary definitions and set the poverty population at forty to sixty million Americans. The official government criteria for determining poverty are based on region of residence and family size. In 1981, poverty income was set at $9,287 for a nonfarm family of four. By this definition, approx�imately thirty-two million Americans were poor. Considering what is required to feed, house, and clothe an urban family of four today, such a figure is appalling. The number one priority among the poor is obviously survival-little wonder, considering the economic depriva�tion in which they live.

Such tension and concern over survival issues tend to bring about a strong present, rather than future, orientation. The future is not something to look forward to if the economic and social horizon is not bright.

Lower-lower class status often has adverse effects on family life. Anxiety over acquiring the necessities eats away at intimacy and harmony within the family. Social life, especially in urban areas, is often not rooted in the home. While in the larger society the home is a place of peace and surcease from the pressures of the workaday world, among those at the bottom of society home is often a nerve-jangling, noisy, overcrowded place. Because homes are not owned by those who live in them and are often not kept up by slum landlords, there is little pride taken in the residence, and hence, little emotional attachment to it.

Pleasures and enjoyable leisure are in short supply in this sector. If one is unemployed, there may be a great deal of free time, but it is often not very relaxing or personally enriching. Pessimism and hope�lessness corrode the spirit.

Despite all the problems of poverty and

inner-city living, there are genuine strengths evident among the poor. Although

family life is often under stress, there are many vital marriages in poverty

commu�nities. Moreover, many solid citizens and battle-tested mature Chris�tians

emerge from single-parent and intact families in inner cities. Dr. William

Pannell, alluding to his

Even in the areas of crime and drug abuse the statistics can be read from two points of view. On one hand, rates do tend to be higher in inner cities and among the poor in general; on the other, they are not so high as to obscure the fact that amid all the deprivation, the majority of inhabitants of poor communities remain "straight."

Out of the crucible of poverty come impressive psychological strengths. The survival mentality gives rise to a resilient form of mental toughness, a courage bred of enduring a difficult existence. Coping skills are highly developed so that crises do not cause panic and the insults of prejudice do not destroy character. More study needs to be made of the strengths among inner-city populations so that strategies can be developed that maximize these skills.

Conclusion. The social-class system is perpetuated by the un�equal distribution of power. While the upper class tends to "own" the society, the middle class dominates and operates it. The result is that the system (whether it is economic, educational, or political) is governed by middle-class rules and styles of operation. For those at the lower end of the system, the middle-class method of operation imposes a dual burden. The poor not only have the usual worries about succeeding, a concern at all levels of society, but they also have to learn rules of the system in which the success game is played. This dual burden produces a great deal of tension among society's "out�siders," tension which many "insiders" neither understand nor notice.

The consequence of this overall power disparity is conflict. It accounts for cleavages between labor and management, the poor and the rich, the government and those governed, and on and on. This is by no means an attack on the capitalistic system, for all political systems have their flaws. The point is that stratification produces winners and losers, and urban pastors are wise to understand the dynamics of the socioeconomic system as a whole, for it accounts for how the winners and losers are determined.

Perpetuation of Social Strata

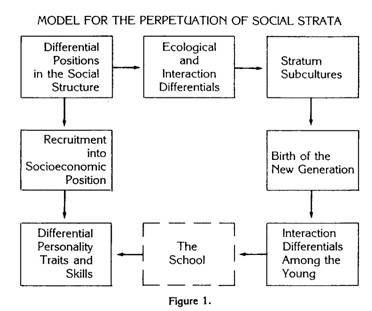

The self-perpetuating nature of the stratification system is a critical element in understanding its inequitable aspects. Sociologists esti�mate (and this is a liberal estimate) that only about one in every four Americans moves up the social structure in the course of a lifetime. In other words, stratification is usually a "womb to tomb" phe�nomenon. Perhaps the best way to dramatize how self-perpetuating the system is, is to use an adaptation of Mayer and Buckley's Model for the Perpetuation of Social Strata (see Figure 1).7

Differential Positions in the Social Structure. The model begins with the adult socioeconomic status. Beyond occupational position, in�come, and level of education, this status has implications for indi�vidual political power, community influence, access to the media, and personal satisfaction.

Ecological and Interaction Differentials. The adult socioeconomic status is related to the social and physical environment. Depending on what socioeconomic stratum a person is in, he will be located in a community of the upper, middle, or lower class. Furthermore, the physical nature of this community-size of the lot, whether buildings are single- or multiple-family dwellings, recreational space, upkeep of the buildings and streets, age of the structures, residential density (people per square mile)-will also differ according to social class. These social and physical elements are powerful in shaping and socializing the individual. Spending time with a certain class of people shapes a person's thinking, and no matter how unpleasant the physical aspects, regularized contact with it brings a certain degree of acclimation.

Stratum Subcultures. This socialization gives rise to classes as subcul�tures. Each socioeconomic layer develops its own particular ways of thinking, feeling, and acting, distinguishable from the other classes. In short, each stratum constitutes a subculture-a mini-way of life.

With regard to subcultures among the poor, there is a debate as to whether the poor hold "poverty values." The prevailing position, the one this author is most comfortable with, is that although the poor are forced to make certain lifestyle adjustments as a result of their scarce means, these adjustments constitute adaptations rather than genuine value differences. As Charles Valentine points out, to posit a true "culture of poverty" may suggest, however subtly, that the poor choose to be poor and enjoy a culture founded on deprivation.8

Birth of the New Generation and Interaction Differentials Among the Young. Within each stratum children are born and the differences in strata give rise to differences in socialization of these children. Lower-�class children become accustomed to large families, limited space, poverty, and insecurity. Few of them will take vacations with their parents. Instead they will develop local "street savvy." Physical toughness and the ability to endure personal deprivation and hardship will likely be fostered. Upper-status youth will associate with other such young people, who have large homes and big yards. They will have their own rooms, stereo equipment, and television. They may travel with their families across the country and perhaps around the world. Food will be in plenteous supply and contact with adults within nuclear family will be more frequent. They will lack few material possessions or creature comforts.

Differential Personality Traits and Skills. These socialization differe�nces will, as already implied, have consequences for the develop�ment of personality traits and skills. What is crucial is that personality�that organized matrix of behaviors, attitudes, values, beliefs, motives characteristic of an individual�is much determined by early socialization experience. Hence, the poor youngster is likely to develop a lifeview congruent with his social background. Street savvy, a job, a car, and freedom from the oppressive burden of poverty are likely to be more immediate goals than a first-rate educa�tion, a white-collar job, or travel.

Although the lower-status youth may well value the same things other children value, his sense of realism, coupled with his limited exposure to a life in a more privileged setting, will likely cause him to act on a different set of values. Exposure to poverty, violence, drunkenness, and police harassment is likely to spawn political and social attitudes consistent with having viewed the effects of these problems. The more affluent youth, who has spent his time among people whose economic and occupational destiny are pretty much under their own control, is more likely to develop a set of attitudes that emphasize individual achievement, along with economic and occupa�tional security.

In terms of skills, the poor youngster is likely to develop abilities vital to surviving the physical and emotional traumas of life. Other children are likely to learn verbal skills, such as reading, writing, and speaking standard English, as well as how to present themselves favorably to the white-collar professionals who determine who will be employed. In short, although the skills learned by those at the bottom are valuable, if not absolutely critical, they will not aid the person in adjusting to or succeeding in the middle-class institutional network, beginning with school and leading to the job market.

Recruitment Into Socioeconomic Position. Once preadult socializa�tion is complete and personalities are shaped and skills developed, the individual is ready to assume his status in the adult structure. And, because of the markedly different set of influences and influencers, according to status at birth, the odds are overwhelming that the person's adult socioeconomic status will be the same as that of his childhood.

The School. The school is placed between the socialization differences and personality traits and skills because its entrance into the child's life occurs at that chronological point. Theoretically, the American school system is designed to equalize opportunity, that is, make certain that success or failure is a function of ability and effort. In short, it is intended to compensate for or eliminate the effect of socioeconomic status at birth. However, the overwhelming bulk of studies conducted by educators and sociologists indicates that, if anything, the school reinforces rather than removes status dif�ferences.9 In fact, the most powerful determinant and the best predic�tor of an individual's achievement in school is his socioeconomic status. This should be no surprise when it is considered that the social and academic skills most rewarded and nurtured by the schools are those highly valued and almost religiously taught in the middle class.

Conclusion. An overall view of the whole self-perpetuating system makes it obvious that instead of every person having an equal likelihood of spending his adult life in any of the classes, one's status at birth largely determines one's adult future. At birth, one is already set in motion-the train is on a track, on a route headed toward an identical adult status. Only a dramatic intervention en route some�where will move the individual off the track and headed toward a different status.

Perhaps the most powerful of American myths is that we are what we are (socioeconomically) because of achievement rather than be�cause we were born that way. It is this myth of self-congratulation and other-degradation that drains away empathy for those who find them�selves at the bottom of the American socioeconomic system. It is this myth that makes it difficult for urban pastors to get help in the form of money or time from affluent congregations and denominations. Peo�ple are thought to be poor because of their own deficiencies, not because of any inherent, self-perpetuating qualities of the socio�economic system. This is not to say that individual effort and achieve�ment are unimportant. It is to say that they are by no means the only dynamics involved. In the final analysis, if urban pastors can over�come this and related antipoverty biases, they will be more likely to gain support and involvement for urban parishes.

NEIGHBORHOODS AND THE

A knowledge of the societal stratification system provides insight into alter systems such as neighborhoods. In fact, Paul Peterson empha�sizes the point that even cities themselves should not be viewed as �nation-states,� or autonomous entities. On the contrary, under�standing a given urban policy requires a knowledge of the wider socioeconomic and political climate. Factors in the state or nation at large, external to a given city, can be determinative of strategy.10 Likewise, an awareness of the stratification of a city and the society at large is vital in diagnosing a neighborhood.

The importance of neighborhood is seen in the fact that people often think in terms of the neighborhood rather than the city in which they live. Richard Coleman, in his work for Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard, writes that neighborhoods serve a variety of functions, including influence on children, adult social comfort, phys�ical safety, and harmony with the surroundings.11 According to Hahn and Levine, even government services are shifting toward a neighbor�hood focus because effective delivery of services requires client cooperation and local governments will not accrue the desired politi�cal benefits without gaining cooperation from receiving neighbor�hoods.12

In this work, the concept of the

neighborhood necessitates ex�panded treatment because it is the direction urban

ministry is going. Defining a neighborhood as a stewardship and service area

provides the urban church with a manageable turf on which to do its work.

Greenway asserts that "the principle which needs emphasizing is that of

the neighborhood church."13 Moreover, such a

geographical ap�proach, based on church resources, increases effectiveness of

pro�grams, which can then be replicated elsewhere by others. Our

Savior's

Types of Neighborhoods

Before looking at examples of what some urban churches are accom�plishing by a neighborhood approach, it is necessary to understand what a neighborhood is and what types of neighborhoods can be found in a city.

Warren and Warren, who do perhaps the best job of showing how to define, organize, and even change a neighborhood, use three basic principles in studying a neighborhood.15 The first principle is identity: To what extent do the people feel they belong to a neighborhood, sharing a common destiny with their fellow residents? The second is interaction: How frequent and in what numbers do people visit their neighbors in the course of a year'? The third principle is linkages: What and how effective are the channels people use to funnel information in and out of the neighborhood?

These three principles are criteria for determining the social structure of a neighborhood. They cut across economic and racial lines and so can be used in any urban neighborhood. On the basis of these criteria-identity, interaction, linkages-six basic types of neighbor�hoods can be differentiated.

The first and strongest type is the integral neighborhood. Here identity, interaction, and linkages are all positive, with the people cohesive and active. They are involved both on the local turf and in the city at large.

The parochial neighborhood is second. There is evidence of sound identity and interaction, but such a neighborhood receives a minus in linkages. These neighborhoods are self-contained, are often very homogeneous ethnically, and are cut off from the larger community.

The diffuse neighborhood has a sense of identity, but little in the way of interaction or linkages. Such a neighborhood is homogeneous, in the sense that it can be a new subdivision or inner-city housing project. However, the neighborhood lacks internal vitality and is not closely related to the larger region. There is little involvement with neighbors.

The "stepping-stone" neighborhood lacks identity, but receives a plus in interaction and linkages. People here are upwardly mobile and involve themselves with neighbors not out of shared interest but in order to get ahead. There is a musical-chairs quality about these neighborhoods: people move through on their way up.

The transitory neighborhood has little identity or interaction. It does have linkages, however. Here population change is evident and the neighborhood breaks into clusters. Often long-term residents are separated from newcomers. There is little joint activity or organiza�tion.

The sixth type is the anomic neighborhood. This has little identity or interaction and few linkages. It is hardly a neighborhood at all because there is no cohesion and there is great social distance between members.

A parish outreach program by the Diocese of Oakland used an interesting approach to analyze their neighborhood. Core church families were each given fifteen to twenty nearby families to visit. The purpose of the visit was to develop friendships and build bridges. From these visits, neighborhood and community needs were defined.

After all the information was gathered and discussed, a parish conven�tion was held in which needs were openly discussed and strategies for action were developed and voted on. Out of this process neighborhood problems were addressed; the church was renewed through prayer, reflection, and action; and bridges were built within the parish be�tween the church and the residents.16

Neighborhood Empowerment

As can be seen in the

Empowerment involves the transfer of control and neighborhood determination from downtown administrative centers to neighbor�hood residents. Neighborhood empowerment is an effort at the de�centralization of power, enabling neighborhood residents to control their own situation. As certainly as individuals in therapy start im�proving once they realize they can do something about their problems, so also neighborhoods are revitalized when self-determination is in evidence.

Hallett makes the

case for empowerment when he says that neighborhoods should be examined in

terms of whether their residents can move from a survival level in which there

is dependence on public aid of some sort, to marginality in which they can

barely make it on their own, to initial accumulation where there is

down-payment money for a house or car, to moderate accumulation with savings

accounts and planning for the future, up to rapid accumulation in which money

begins multiplying itself.17 Samuel Acosta, at a con�ference of

churches-in-transition held in

Unhooking a neighborhood from

dependency on outside pro�gramming and resources is basic to empowerment. What

is necessary is public investment in neighborhoods rather than public aid

mainte�nance dollars that assure barely a survival level.19 Too

often public aid monies earmarked for needy city dwellers never reach them. For

example, over 50 percent of government monies targeted for the poor is funneled

through Medicaid and Medicare, so that much of it goes into the pockets of

professional distributors. Sometimes the profes�sionals are less than ethical.

In

Neighborhood empowerment requires organization and plan�ning. It means addressing issues on a variety of fronts. Such issues include influencing institutions and businesses to hire neighborhood residents; gaining a voice in the administration and operation of schools; gaining control by means of property ownership; demanding proper and responsive political representation; improving health care, perhaps by developing an organization such as a health maintenance organization that yields benefits for staying healthy; obtaining greater commitment and improved services from financial institutions. In addition, with the rise of modern government administration systems, impact urban political structures requires dealing with appointed bureaucrats rather than elected officials.20 Thus a key neighborhood empowerment issue is gaining bureaucratic accountability.

Marciniak, a veteran of urban revitalization, suggests twelve strategies for improving and empowering neighborhoods.21

1. Mobilize voters to clean out political figures who prey on neighborhood �misery.

2. Work toward eliminating or reforming day-labor organizations through competition. Day-labor organizations hire unemployed residents �on a day-by-day basis to do contracted work. The workers are �paid in cash at the end of the day. The profits are raked in by the organization, which, in some cases, encourages willing workers to bribe the officials in order to get a job for a day.

3. Work with the electorate to rid the area of undesirable liquor establishments and other trouble spots.

4. Deal head-on with the neighborhood's concern about street crime.

5. Provide escort service and other moral support for witnesses to appear in court in cases dealing with street crime and intimidation.

6. Work at cutting through bureaucratic barriers in removing aban�doned autos.

7. Approach public officials to stop licensing any more sheltered care facilities such as nursing homes or half-way houses for the mentally disturbed until the community has had time to deal with the ones already there.

8. Encourage local institutions to remain and adapt to changing populations and lifestyles.

9. Promote investment in older, multiple-family dwellings in order both to renovate neighborhood housing and avoid the development of a slum.

10. Urge new "urban pioneers" to take residence in the neighbor�hood and work toward its continuing revitalization.

11. Demand that city officials not inundate the neighborhood with public housing, but rather allocate such developments on a "fair share" basis.

12. Capitalize on the power of local institutions whose own futures are linked to the well-being of the community for support and strength.

A Stewardship Ministry

Working toward empowerment is a stewardship rather than service ministry. The church must get beyond the old missionary model in which a missionary goes into an area with all his expenses and salary paid by outside sources and then performs a relief ministry. In the urban church that kind of approach is seen in using the church as a clubhouse for activities and as a dispenser of services to the needy. As important as relief ministries are, the church must go beyond being an ecclesiastical version of the welfare system.

Many churches are making this move. The

community garden program in

In the

Efforts at neighborhood revitalization

are greatly enhanced by building coalitions. In

Coalitions abound. The Archdiocese of

St. Paul and

In the South Bronx, seventy-nine black churches from a variety of denominations joined together to form the Shepherd's Restoration Corporation, which supports housing, economic, and other social activity in the Bronx. 26

In

In

Empowerment efforts are aided by strength of unity. This is especially important because these efforts often mean dealing with institutions, the topic of the next chapter.

4: Poverty From an Institutional Perspective

The truths of stratification and self-perpetuation of the socioeconomic system are not widely known or accepted. As a result, negative attitudes toward the poor persist.

The perpetuation of poverty by society results partly, as Har�rington points out, from its invisibility.1 It is very difficult for people to become concerned about problems with which they are not confron�ted. In cities, the poor are so severely segregated that a person can live for years in an urban metropolis without ever driving to a poor neighborhood. When poverty is an abstraction, it is exceedingly difficult for many middle-class people to believe that there can be as many as thirty-two million people in this country living below the poverty level. This invisibility is exacerbated by the immobility of the poor. Many are unable, because of physical illness or financial deprivation, to leave their neighborhoods. So just as the middle class do not go into poor neighborhoods, neither do the poor make their way into middle-class neighborhoods.

To argue that poverty is a self-perpetuating condition in a capitalistic society is to attack the nation's sacred civil doctrine of the self-made �person. To suggest that one is poor because of an unequal distribution of opportunities is to suggest that riches are as much a matter of good fortune as virtue.

Ironically, a middle-class person has no feelings of inferiority about not being truly rich, for if asked why he is not more affluent, he will be quick to tell of his roots and how these precluded the opportunity for acquiring great riches. Yet this same individual cannot accept the similar accounting for poverty. Elliott Aronson says we are rationalizing rather than rational entities.2 Never is that more in evidence than in our being critical of the poor while excusing our own failure to reach the economic heights to which we would aspire.

INSTITUTIONS AND THE POOR

In spite of the many poverty myths, poverty means much more than absence of money. It is powerlessness and alienation from the key institutions of society. The importance of the lack of integration of the poor in the major institutions of the society is highlighted by Oscar Lewis.3 Although, as Lewis rightly contends, urban and rural poverty share many characteristics, urban poverty is distinctive in that the city's poor feel a heightened sense of powerlessness and confusion as they deal anonymously with massive, impersonal bureaucracies, bu�reaucracies in which size and officialdom have an intimidating effect.

In many communities multistoried government buildings are filled with middle-class personnel whose main task is to orient aimless poverty victims to the prevailing system, referring them to em�ployment centers, health clinics, neighborhood mental health offices, special school programs, city services pertaining to public aid and building maintenance, legal aid agencies, and on and on and on. Probably no characteristic of urban poverty stands out more than this lack of experience and familiarity with basic urban services and agencies.

Sociologically, institutions are

abstract collectivities that meet basic human needs. In

The urban poor are almost completely cut off from the wider society and yet are oppressively controlled by it. They are usually geographically separated from "polite society," but the power fig�ures of the city hold tight control over what are euphemistically called "poor neighborhoods." The police are ever-present, the politicians regularly "ride herd" in the ghetto areas, the schools teach a main� stream lifestyle, large denominations constantly dictate policy to their "urban missions," and the welfare system keeps tight rein on the lifestyle of public-aid recipients. The feeling of oppression�of a noose around a poor neck�often creates a volatile climate in the inner cities.

Politics

Politically, the poor are all but without representation. Not a single senator or congressman is noted for championing the cause of the poor. In fact, almost every well-known figure who is viewed as an advocate of the poor is outside the prevailing system. Jesse Jackson and Cesar Chavez are two examples. The poor are minimally repre�sented because in a capitalistic society they produce little in the way of goods and services. What is more, with mass disorganization and estrangement, coupled with little stable community leadership, they vote in low numbers, making them almost irrelevant to well-dressed, high-powered political candidates.

In poverty areas can be found the

classic example of political reversal. Instead of the political system

depending on the support of the people, the people depend on it and so become

the pawns of the political system. A housing issue in a

A mass meeting over a housing grievance was held in one of the neighborhood's churches. City officials, neighborhood residents, and community workers were present to hear the matter. The conflict was resolved, the city officials assuring the citizens that they would make good on their vows to provide and maintain adequate housing. A subsequent meeting was scheduled for a month later to check on the officials� progress toward honoring their promises.

A month passed and the day of accountability arrived. Much to the surprise of the community workers, neither the aggrieved neigh�borhood residents nor the city officials showed up. The church hall nearly empty. A bit of investigation revealed a political coup. Apparently an official from his downtown city office called the tenant council in one of the high-rise buildings and stated that he was privy to rumor that if the meeting were held as scheduled, the welfare checks, on the third of the month, would be late in arriving. Faced with a choice between improved housing or food, the residents quickly capitulated to the threat and the meeting was boycotted. For the city, it was the perfect squelch. They claimed publicly that they had ob�viously done their job well, for the community, by virtue of their nonattendance at the meeting, showed that the matter required no further attention.

Often people wonder why inner-city citizens who do vote, vote for the same political regimes that are said to have held them down. There are several reasons for this trend. One is a lack of alternatives. A known half-loaf is better than no loaf at all. However, more impor�tantly, the voters are often intimidated. It is common for local political organizers to roam the streets and subtly but clearly warn the citizens that if candidate "X" does not receive adequate support at the polls, he will have little reason to serve the community well. Translated, that means that fire protection may be even more lackadaisical than before, police service will become increasingly oppressive and decreasingly protective, project buildings will be ignored, slum landlords will be under even looser control, and garbage may continue to pile up, making the rat and roach epidemic even worse.

Little political organization and savvy and a resulting lack of power account for the reason so few changes are made in the inner city. An urban church worker learns quickly that the people are not only beset with ineffective governmental programs and policies but, even worse, are without realistic grievance mechanisms to ameliorate these problems. In fact, many welfare-oriented government programs exist simply because of political powerlessness, and although they may be designed with the best of intentions, they are just substitutes for what is really needed: an equitable share of political power in a representative democracy.

Religion

Religion, as an institution, is also tainted by poverty. In many inner cities the church is the only really caring agency of any enduring value. It is a meeting place, a fellowship center, and a source of support. However, these churches almost invariably exist on a hand-to-mouth basis. This problem is growing. For example, according to Richard Gary's research, by 1987 half of all Episcopalian churches will not be able to support a full-time pastor.4

Urban church staffs are small, with many positions filled by volunteers. There is a great need for professionalism and urban expertise, but there is simply no money to fund the programs that could use trained personnel effectively. If the church is nondenomina�tional, it lives off the income garnered from the collection plate. Such a budget would provide only for the minister, if even that. In many cases, an indigenous pastor is only a part-time professional, spending most of his time working in a factory or a store in the neighborhood. If the church belongs to a mainline denomination, it is most likely on that denomination's home missionary budget, receiving a monthly pit�tance to carry on the awesome task. In short, another reversal is in operation. The churches that need the money for comprehensive and effective whole-person ministry receive the least support, while other congregations debate whether to purchase a new organ or better sanctuary carpeting.

Economics

Poverty in economics connotes much more than simply a lack of money. High unemployment and underemployment mean a dearth of opportunities to acquire money.

Much of the insensitivity of middle- and upper-class people toward the poor is an outgrowth of the Protestant work ethic. The Protestant work ethic in its oversimplified form suggests that if one works hard, one will attain success. It is a strongly procapitalistic religious doctrine, emanating from the notion that God blesses those He favors and, therefore, if one is living in God's favor and laboring faithfully, success will result.5 Much of the Protestant ethic is valid, one would be hard-pressed to find many truly successful people who have not worked very hard at achieving that success. In that that respect, its endorsement of hard work and attention to duty is sound. The problem comes with the Protestant ethic's unwritten corollary: If one is not successful, one has not worked hard.6 Once that corollary is accepted (and it is subtly taught throughout the nation's schools and churches) the seeds of prejudice toward the poor are well planted. One aspect of this problem is that many people cannot understand why there is so much unemployment in the inner cities. A look at the daily papers reveals legions of job opportunities.

This issue merits examination. If one takes a close look at those ads, it becomes apparent that there really are not very many jobs for the poor. First, many of these jobs require a substantial amount of education. Even those jobs that require less formal education still require well-developed literary skills. These requirements eliminate most of the poor. Second, many of the factory jobs listed are not located close to poverty areas. Many industries, and hence jobs, have moved to the suburbs. Third, of these jobs that remain, many pay the minimum wage. At the minimum wage times forty hours, the vast majority of low-income families earn below the federal poverty level. In addition, job-related expenses such as travel, perhaps baby-sitting, clothes, and other mundane items, make it even less economical to accept such employment.

In the early seventies, a large candy

manufacturer felt compelled to do something to relieve the pain of unemployment

in