By Michael Paulus Jr.

At the end of his recent book The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction, Alan

Jacobs includes a glorious quotation from the medieval English bishop and bibliophile

Richard de Bury: “All things are corrupted and decay in time … all the glory of the world would be buried in oblivion, unless God had provided mortals with the remedy of books.”

Jacobs, an English professor at Wheaton College, invokes Richard in support of his excellent case for the joy of reading in our information- and media-rich age. But Richard, in addition to making a case for reading texts, was concerned about caring for books as physical repositories of knowledge.

The 17th-century Spanish printer Alonso Víctor de Paredes said that a book, like a human being, has a dual nature: It consists of both a soul and a body. If we are able to read about the glories of the world over time, it is because messages about them — and the material forms that contain and carry these messages — have been kept from corruption, decay, and oblivion.

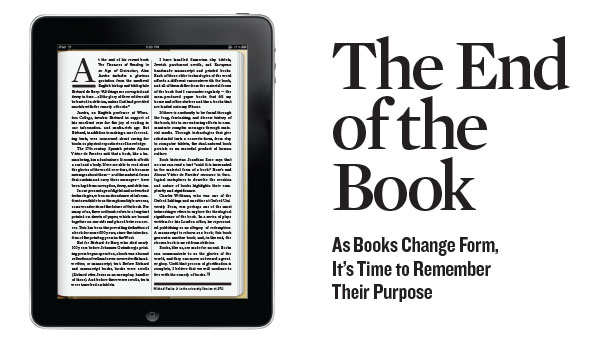

In our present age of digital and networked technologies, when an abundance of information is available to us through multiple screens, some wonder about the future of the book. For many of us, the word book refers to a long text printed on sheets of paper, which are bound together on one side and placed between covers. This has been the prevailing definition of a book for some 500 years, since the introduction of the printing press in the West.

But for Richard de Bury, who died nearly 100 years before Johannes Gutenberg's printing press began operation, a book was a bound collection of vellum leaves covered with handwritten, or manuscript, text. Before Richard and manuscript books, books were scrolls (Richard cites Jesus as an exemplary handler of these). And before there were scrolls, texts were inscribed on tablets.

I have handled Sumerian clay tablets, Jewish parchment scrolls, and European handmade manuscript and printed books. Each of these older technologies of the word affords a different encounter with the book, and all of them differ from the material forms of the book that I encounter regularly — the mass-produced paper books that fill my home and office shelves and the e-books that are loaded onto my iPhone.

If there is continuity to be found through the long, fascinating, and diverse history of the book, it is in our enduring efforts to communicate complex messages through material media. Through technologies that give substantial texts a concrete form, from clay to computer tablets, the dual-natured book persists as an essential product of human culture.

Book historian Jonathan Rose says that no one can read a text “until it is incarnated in the material form of a book.” Rose’s and Alonso Víctor de Paredes’ recourse to theological metaphors to describe the creation and nature of books highlights their complexity and significance.

Charles Williams, who was one of the Oxford Inklings and an editor at Oxford University Press, was perhaps one of the most interesting writers to explore the theological significance of the book. In a series of plays written for his London office, he represented publishing as an allegory of redemption: A manuscript is reborn as a book; this book generates another book; and, in the end, the chosen book is saved from oblivion.

Books, like us, are made for an end. Books can communicate to us the glories of the world, and they can move us toward a greater glory. Until that process of glorification is complete, I believe that we will continue to live with the remedy of books.

Michael Paulus Jr. is the university librarian at SPU.