Web Feature Posted April 26, 2012

Filmmaking Like Jazz: Steve Taylor Brings Donald Miller’s Best-Seller to the Big Screen

By Jeffrey Overstreet (jeffreyo@spu.edu)

Don Miller (Marshall Allman) and Penny (Claire Holt) are caught in a web of cynicism and religious intolerance in Blue Like Jazz. Photos by Jonathan Frazier. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions.

Don Miller (Marshall Allman) and Penny (Claire Holt) are caught in a web of cynicism and religious intolerance in Blue Like Jazz. Photos by Jonathan Frazier. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions.

If you recognize the name “Steve Taylor,” you probably aren’t thinking, “Oh, yeah … the filmmaker.”

Instead, you’re remembering a controversial Christian rock star from the 1980s and early ’90s, whose music was often scathingly satirical and provocative. Instead of serving up standard praise anthems and polished pop, Taylor took a rougher road. He warned listeners about the lies prevalent in pop culture, even as he played a sort of court jester to evangelical culture — singing about the dangers of compromise, hypocrisy, arrogance, and hero worship in the church.

Many have hoped for a comeback. And here he is, reinventing himself as a filmmaker. Taylor is the director of Blue Like Jazz, Roadside Attractions’ big-screen adaptation of Donald Miller’s New York Times best-selling memoir.

And surprise, surprise — Blue Like Jazz is a lot like a Steve Taylor album.

It tells the story of Don Miller, a Southern Baptist boy who becomes disillusioned with his evangelical community and heads off to a new world, the liberal wonderland of Reed College in Portland, Oregon. There, he is humbled in ways that may inspire Christian viewers toward self-examination. What’s more — he witnesses the revolutionary potential of the Gospel in unexpected ways.

Like Taylor’s music, Blue Like Jazz provokes with questions more than answers, encouraging us to see what the diseases of conceit, hypocrisy, and fear can do to the witness of the church. At the same time, the movie is an engaging coming-of-age story about a young man’s efforts to expose hypocrisy, survive betrayals, and find a life of integrity among friends who hold starkly contrasting views.

Adapting the book proved to be a daunting endeavor. The movie’s “Don Miller” is a fictional version of the real Donald Miller, and the story is only loosely inspired by certain events in Miller’s life. Taylor, his co-writer Ben Pearson, and Donald Miller himself were tasked with inventing a coherent, engaging storyline that would illustrated the core ideas of Miller’s testimony. Thus, the movie feels like an experiment. It’s a quirky romantic comedy. It’s a story about a search for authentic faith in a world disrupted by hypocrisy, fear, and intolerance.

It’s remarkable that the movie was made at all. After production began, the film’s main source of funding withdrew. But the movie’s supporters came to the rescue, launching a Kickstarter campaign that brought in more than $300,000, making Blue Like Jazz the most successful film project ever developed through that fundraising service. That’s still a miniscule budget compared to most big-screen endeavors, and the film has some obvious rough edges because of those limitations. But it’s a testament to Taylor’s creativity and resourcefulness that the film is so engaging and enjoyable, and that Roadside Attractions picked it up for distribution.

While some mainstream critics have been put off by the film’s exploration of faith-related themes, others have been impressed, saying it stands apart from other so-called “Christian movies.” The AV Club’s Nathan Rabin says it’s “surprisingly nuanced, even-handed,” and The Washington Post’s Michael O’Sullivan was relieved that it is “somewhat surprisingly … neither sanctimonious nor preachy.”

Talking to Response, Taylor said that the contrarian culture of Reed College responded quite positively too.

That’s an encouraging sign for Taylor’s future as a filmmaker. And it should inspire others who seek to cultivate cross-cultural dialogue about matters of art, culture, and faith.

A Conversation With Steve Taylor, Director of Blue Like Jazz

Response: Your movie, like your music, seems designed to provoke Christians to some discomforting self-examination. Is it just in your DNA to make that kind of art? Can we expect more of this kind of thing?

Taylor: Part of the appeal of Blue Like Jazz was that it was a story I felt I could tell well. It struck a lot of chords. I think one understandable critique on my first movie [The Second Chance] was that it was a pretty conventional story. It didn’t feel like subject matter that I would naturally be drawn to, based on my music career. But Blue Like Jazz felt like … “I get this.”

I’ve lived it, too — going to a school in Boulder after growing up in a Baptist church.

I don’t have a very long attention span, so I wouldn’t want to the next project to be something too similar. But it was sure fun making this one, and to feel like I intuitively understood the main character’s central conflict.

And yet, this movie is playing for general audiences — even at Reed College, in the environment that poses so many challenges for the main character. What was that like?

It was wild! They have something called the Gray Fund to bring cultural events to campus, and our screening drew their biggest crowd ever.

And how did they respond to your depiction of their culture, and to that three-day campus festival — Renn Fayre?

Reed is a famously closed society. When they do Renn Fayre, they don’t allow anybody else on campus. I actually attended Renn Fayre two consecutive years to do research, and I had to get special permission both times. I couldn’t take any photos or video, all I could do was text myself notes while my production designer made sketches. They like the fact that there’s a mystery to it.

Don [Miller] introduced the film, and he did a wonderful job of making funny excuses and sort of apologizing for portraying Reed’s culture. He said, “Listen, I’ve attended a lot of classes at Reed. I kind of understand the theme here. So if you want to go full-on Mystery Science Theater during the screening, feel free. And they all cheered and took full advantage of it.

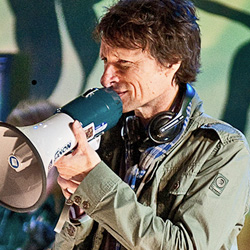

Megaphone Man: Steve Taylor directs Blue Like Jazz. Photo by Jimmy Abegg.

Megaphone Man: Steve Taylor directs Blue Like Jazz. Photo by Jimmy Abegg.

I had told them ahead of time, “We would have loved to have filmed the whole thing here at Reed, but we didn’t have enough money. So you’re going to see a mix of Reed College and another location, and we apologize for that.” So every time Reed College showed up, they cheered, and every time another location was substituting for Reed, you heard scattered boos and hisses.

They tended to like the dialogue, but there were other times when you’d hear catcalls about certain things. We had some walkouts, but Don was pacing outside on the campus, and he noticed that some people were going out to get high and then going back in to finish watching the movie.

At the end we got a long, extended ovation and a large number of students stayed around afterward to talk.

The consensus from students I spoke with was, “We came tonight, not wanting to like it, but we have to admit that you got the environment pretty close.”

Well, if people are getting high during the movie, that may give it a promising future right there. That’s worked for a lot of cult classics!

(laughing) Whatever it takes ...

You had to create a variety of characters that have different lifestyles and worldviews. There’s some argument about whether those characters ended up seeming like stereotypes. Did you talk about that as you were writing filming?

Everybody’s entitled to their opinion, but that’s an opinion I’d argue with — we went with a lot of stories that were based on Don’s time on campus, combined with other things I picked up during my time there.

It’s a very unique, very contrarian environment. How do you make up something like “the Scrounge Counter” or “the Pope of Reed College”? There are party schools, and there are classic liberal arts schools, and there are ivy league schools, but I’ve never seen an environment quite like Reed, and I feel like our Reedie characters captured the spirit of the school pretty well.

Did the script go through a lot of revisions?

We were always tinkering with the script. We tweaked it even more during the filming. Don was there during a lot of the filming. The cafeteria scene — he came up with a good revision just a couple of days before that I thought played really well.

We shot the whole script. Usually you end up cutting about 20 percent and that’s about what we cut — a few ideas didn’t make it to the final cut because we just weren’t pulling them off.

The biggest thing that changed was the beginning: It was difficult to get Don to Reed College as soon as possible, so we kept whittling down the first act. The first 10 minutes still feel long to me. That was the toughest part: How do we get people to care about Don before he gets to Reed?

It felt to me like you could have made a whole movie just about what was happening in his home church. Those episodes seemed to get the biggest laughs.

People could argue that what we showed in the church was over-the-top, but you and I have enough experience in that kind of environment that we know better.

How did Roadside Attractions come to distribute the film?

I like a lot of the movies they’ve put out. I think they have good taste. And on the business side, I feel like they make the most of everything they release. I met them fairly early in the process. They were the first people we screened it for, and they responded immediately, so there were never any serious talks with anybody else. That was always the company we were hoping to work with.

What have you learned from this? Do you have it in you to make another movie?

Ben came up with an idea that he pitched to Don and me, and we both really like it. We’re hoping to go to work on it after we take a break. But making movies is hard. I’m not good at raising money, and I never have been, but it comes with the job, since even doing an indie movie on a budget is expensive. The way this movie finally came together on Kickstarter was a big surprise and an unbelievable blessing. But I’d prefer it if the next movie didn’t take four years to get funded.

The soundtrack was impressive all the way through. I’ve been a fan of Menomena for a while, and their score worked very well. It was good to hear you doing a song over the end credits. And Over the Rhine’s Christmas song fit in like it was written for the movie.

Yeah, that’s such a beautiful piece.

You dropped a hint on Facebook that we may be hearing new music from you soon.

I got so frustrated when I felt like Blue Like Jazz was failing, that out of creative frustration I ended up going into the studio with Peter Furler, and then John Painter (of Fleming and John), and then Jimmy Abegg, who’s a longtime friend, guitarist, photographer and visual artist. And we just started recording. Peter had written some music ideas, and I love his melodies. We worked up the songs as a band, then I added lyrics. We were about a month away from having something finished when the Kickstarter campaign started, and it was like, "Oh, man … we’re making a movie." And it’s just been on hold for the last 18 months, because finishing the movie has taken up all my time.

That’s one thing I’ll do once things settle down — get back together with the guys and finish that project up.

Any lessons learned the hard way?

People who aren’t filmmakers don’t realize how much money affects everything. It’s hard to make even a bad movie. But it’s really hard to make a decent movie when you’ve got such limited resources. So you’re always trying to find ways to work around that central reality of not having enough resources to do what you want to do. It affects everything — even in a big movie.

I was reading about The Hunger Games. I love those books, and I liked the movie, but it didn’t blow me away. I was reading about it, and a lot of their choices were flat-out based on money. Eighty-five million bucks is a lot of money, but it’s not John Carter money, right? So there’s a lot of handheld camera work going on in different scenes, and that’s because handheld means you’re not laying dolly tracks or setting up cranes, which lets you shoot more pages each day. I’ve heard The Hunger Games criticized for all the handheld camera work, but … I don’t think they would have made that choice if they didn’t have limited money and didn’t have to get certain things done in time.

There’s such a direct correlation between how much money you have and what you’re able to do or not do with your budget parameters. We’re better off as indie filmmakers studying South Korean filmmakers or Eastern European filmmakers — artists who have to do a lot with little. I admire the aesthetic of, say, the Duplass Brothers’ movies, but there are ways to bring bigger production value to indie movies without having gobs of money.

And then there are things you want to do in post-production, but you’ve used up your budget and can’t afford what you believe the movie needs. There’s still a lot you can do, and there’s a lot you can do in writing a story that doesn’t demand a big budget in order to make it look convincing. But money is the harshest reality of them all when it’s time to start shooting.

I read one critic complaining about sound quality.

I saw that one, and as someone who knows a bit about sound, I thought that was a very odd complaint. Not all movies have the money to camp out at Skywalker Sound for multiple months. I think our movie sounds great, and it’s all the more remarkable given how little money we had for post-production sound.

It’s interesting that The Tree of Life, which was rich with Scripture and questions about faith, did not inspire the kind of enthusiasm among evangelicals that something like Courageous did. Blue Like Jazz is also about a Christian who struggles with questions, and Jesus doesn’t fix everything in the end. It feels like the audience for “Christian movies” gets excited about message-driven movies that resolve neatly, instead of art that’s more interested in questions and mystery. Do you think that will change?

It’s funny you’d mention The Tree of Life. That movie was not only one of the most inspiring movies I’ve seen in the last few years, but it also had the inverse effect of “Why do I even bother when it gets as good as this? What hope is there for the rest of us?”

The Christian music industry is an interesting parallel to what’s happening with Christians and movies, in some regards. Christian music, as an industry, started where it did because there really wasn’t anywhere else to go. Mainstream music wasn’t really interested in Jesus music. Then, Christian music became institutionalized, and then it became a box.

Then along came breakout bands like Sixpence None the Richer, Jars of Clay, POD, Switchfoot — a while after that I was reading a New York Times article where they were interviewing A&R execs at major labels who were talking about seeking out Christian bands because they were better bands — they had a live concert circuit they were playing, and they were writing great songs and making great recordings. I didn’t think I’d see something like that in my lifetime, and the fact that it happened was remarkable.

Today, Christian music is a much smaller scene. Part of the reason it’s a smaller scene is because a lot of people that otherwise would be in Christian music now have broken through that “glass ceiling” and they’re making all kinds of music for all kinds of people in all kinds of places.

When it comes to Christians in filmmaking, you and I know people like Scott Derrickson who are masters at what they do but they would never be interested in being part of a “Christian film scene.” Hopefully this Christian film scene will shrink in the coming years because Christians will be telling a wide variety of stories for a wide variety of people.

Read more reviews in the Response OnScreen archive.

Did you read or see Blue Like Jazz?

Tell us what you thought in this moderated board. And see what others say.