Built With Words

What Chemists and Poets Have in Common

By Benjamin McFarland

When he was six, my son Sam told me that when he grew up he wanted to be a scientist and a builder. Not "or," but "and." My first thought was that he was going to have to choose one of those someday. But on further reflection, I think he could do both — I think I do both.

I am a biochemist, and chemists are builders and "makers." One chemistry lab has made an artificial leaf. Another has made an analysis system for chemicals — out of paper! Another is trying to rebuild DNA with different atoms. My own biochemistry research for the past eight years at SPU has been a quest to make something, too. So although I work with both biology and chemistry, at heart I must be a chemist.

And at every step along the way, the building of chemicals requires us chemists to build arguments from words, from the first grant proposal to the final published journal report. Words make the case for what we want to build, or to show that what we have built actually works. I wrote far more words after I became a scientist than before. Clear writing leads to clear thinking, and to think clearly a chemist must build well, with words. In this sense, the line between the chemist and the writer — even the poet — is blurred.

The fact that poets build with words is contained in the very word "poet." "Poet" comes from "poieo," Greek for "I make" or "I do." The original poet was not an abstract, esoteric academic, but a maker, a builder of meaning for the community who put words together in strange and new ways. Poets build with words; chemists build with atoms. Poets are made of atoms; chemists must use words.

Even as late as the early 19th century, makers were makers, and modern categories were not solidified. The chemist Humphrey Davy made pure potassium and also published poems. The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote "Water, water, every where / Nor any drop to drink" with the same hand that also conducted chemistry experiments. In The Age of Wonder, biographer Richard Holmes describes this era vividly.

The increasing specialization and speed of science pushes these disciplines apart, but there are glimmers that they can be put back together. One of the most fascinating hints of this is a fact that has now become common knowledge, a secret hidden in plain sight: At the center of every living cell is a set of microscopic words called DNA.

If DNA is made of words, then all life is built from a very strange poem.

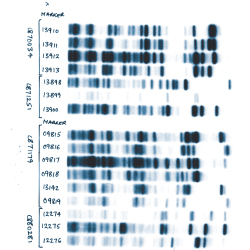

DNA is often called the blueprint of the cell, but that metaphor may be too complex. A blueprint is a set of drawings on a two-dimensional sheet of paper. DNA is a one-dimensional string of just four letters. Creatures from bacteria to humans all use the same four letters, arranged as genes, which happen to look a lot like words.

This means that I can type out a complete set of genes, an entire genome, on my computer keyboard and never touch most of the keys. It would take a while — there are billions of these letters in a genome, just as there are billions of words in the library — but they are all made from the same few letters and arranged in straight lines. They are all essentially words.

DNA tells the cell how to build proteins, which are words in a different "language," this one written with twenty amino acid letters. To build a cell, words make words, and the system of all these chemical words coalesces into the breath of life. From this, layers upon layers of meaning emerge, until, after generations of mute plants and animals, one creature starts to use words again to communicate and to create. Those words make us human.

"If DNA is made of words, then all life is built from a very strange poem."

In the decade since we've been able to read most words in the human genome, we've found that this language is very strange, even alien. The genome is an ancient text, scarred with the passage of time, revised and rewritten like a palimpsest, at times burned like the Library of Alexandria. It is an "ecosystem" of words, fluid, active, and effective.

Its dark corners are still closed to our understanding. Deciphering this secret code is an inspiring challenge. The good news is that literary scholars have been tracing the origins of languages and words for years, and we can use what they have learned with genomes.

In my 2011 Day of Common Learning presentation at Seattle Pacific University, "Trees of Life," I described how this might work in one particular case. The old DNA word for a thioredoxin enzyme was deduced by comparing lots of modern thioredoxins, just as literary scholars deduce ancient word roots from commonalities across languages. The old enzyme is sturdier, broader than the modern enzyme in function (its "meaning") and surprisingly sophisticated. As J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis' friend Owen Barfield wrote in Poetic Diction: "Really, there is no distinction between Poetry and Science, as kinds of knowing, at all. There is only a distinction between bad poetry and bad science."

How appropriate is it, then, that God spoke words to build all creation? Or that we are told that "day after day" his creations "pour forth speech"? Or that when he was born at Christmas that "the Word became flesh"? And how fitting is it that Paul says we are his "workmanship," his creation, his building, his poem? We are made for, and with, these words.

Benjamin McFarland is an associate professor of biochemistry at SPU. An expanded treatment of these topics will appear in his essay in the forthcoming book Faith Seeking Understanding: Essays in Memory of Paul Brand and Ralph Winter, edited by David Marshall.