From Discovery to Eradication, Missionary Doctor Ron Guderian ’67 Helped Empower Communities to Rid Themselves of Disease

By Hannah Notess (hnotess@spu.edu) | Photos by Bear Guerra

The woman had a lump near her spine, about the size of a lemon, that was bothering her. It was making it hard for her to sleep. Would the doctor be able to remove it? She spoke, not to the doctor, but to her husband, who spoke on her behalf. At that time, in 1976, in the culture of the Chachi, an indigenous Ecuadorian tribe living in the coastal rainforest, married women did not speak directly to men other than their husbands. So her husband came to her appointment as the go-between.

Portrait of San Jose de Cayapas elder, Celestino Nazareno,

whom Guderian has known for several decades. Nazareno

was one of the first men in this village to be found infected

with river blindness due to his having worked up river where

transmission of the disease was high.

Portrait of San Jose de Cayapas elder, Celestino Nazareno,

whom Guderian has known for several decades. Nazareno

was one of the first men in this village to be found infected

with river blindness due to his having worked up river where

transmission of the disease was high.

![]() Photo gallery

Photo gallery

The doctor, Ron Guderian ’67, examined the lump. He and his team, a mobile medical unit based at Hospital Vozandes in Quito, had traveled three days up the Cayapas River to offer medical care. The lump was hard to the touch, moveable, and it wasn’t causing her pain. Yes, he told her, they could. When they performed the surgery, though it’s been nearly 40 years, Guderian can still easily describe in clinical detail what they found:

A thin, threadlike worm, 60 centimeters long, inside a fibrotic capsule. It was the parasite Onchocerca volvulus, a worm that can live for up to 14 years in the human body. It causes the disease onchocerciasis, better known as river blindness. The parasitic worm lives in nodules in human skin and procreates, producing about 10,000 larvae or microfilariae daily. The microfilariae cause intense itching, skin rashes, and skin damage. If the microfilariae enter human eyes, they can cause vision loss, leading, if untreated, to permanent blindness.

What he didn’t know then was that the quest to eliminate river blindness would come to define the next decades of his career. He didn’t know that he’d end up working with doctors and scientists from around the world, co-authoring dozens of research papers, and working for the World Health Organization on global efforts to combat river blindness. Nor did he know that in 2014, the WHO would declare river blindness officially eradicated from Ecuador.

What Guderian did know — or thought he knew — from his doctoral studies in tropical medicine, was this: River blindness was an African disease. It wasn’t supposed be afflicting people in the most isolated part of the Ecuadorian jungle.

“How in the world did it get here?” he wondered.

Life on the Río Cayapas. In Loma Linda, an elderly indigenous Chachi matriarch peels plantains while sitting on the raised open-walled platform of her traditional home.

Life on the Río Cayapas. In Loma Linda, an elderly indigenous Chachi matriarch peels plantains while sitting on the raised open-walled platform of her traditional home.

River of Life

The story of river blindness’ arrival in America is wrapped up in a much bigger and sadder story of the abuse of power — that of the slave trade. Spanish traders, looking for gold mine workers, enslaved people from Africa’s west coast, Cameroon and Ghana. Off the coast of Ecuador in 1553, a slave ship bound for Peru was wrecked, and the slaves who escaped made their way to freedom and became the first Afro-Ecuadorians. The coastal province of Esmeraldas became a safe haven for escaped slaves from around Latin America, and is still populated primarily by Afro-Ecuadorians today. They are known for, among other things, their marimba music and their success in soccer — a number playing on Ecuador’s national soccer team.

Waterways are the lifeblood of these communities — and the lifeblood of the Chachi, the people indigenous to the area who lived further upstream. Though historically separate, both communities live along the rivers that thread through the dense, coastal rainforest. The river is transportation: there are no roads, and children ride in canoes to school. And the river is a source of sustenance for their fish-based diet.

Grade school children gather as classes get underway in San Miguel. Middle and high school students must travel downriver by canoe to another village to attend school.

Grade school children gather as classes get underway in San Miguel. Middle and high school students must travel downriver by canoe to another village to attend school.

But the river is also the breeding grounds for Simulium exiguum black flies. River blindness, like malaria, is a vector-borne disease, which means the disease-causing organism (the worm) relies on a vector (the fly) to spread. Having arrived from Africa, the worms used flies to spread from the coast to the rivers, as people migrated. The first case in the Americas was documented by Guatemalan physician Rodolfo Robles in 1915. Ultimately, it would be found in six American countries, 30 African countries, and in Yemen.

In Ecuador, it was spreading all too well. In fact, as Guderian would discover, the farther upriver, the more flies were present — and more disease. In the most remote communities 100 percent of men, women, and children showed signs of microfilariae in their skin.

If they didn’t receive treatment, every single person in the village could go blind.

With that information in hand, he and his team went back to the tribal leaders and met with them to present their findings. The chief, Pedro Tapuyo, spoke up at the meeting.

“Well, doctor,” Tapuyo said, “now that you’ve shown us that we all have this infection and we are going to go blind, what are you going to do about it?”

“That question is what changed my whole course,” Guderian says.

Transmission Status in the Americas, 2014

Decades of global efforts have paid off,

and onchocerciasis is eliminated in more

than 75 percent of affected populations in

the Americas. Transmission only continues

in a remote area of the Amazon rainforest

on the Brazil/Venezuela border. In Africa,

where onchocerciasis is much more prevalent,

community-directed treatments are

beginning to show good results, reducing

the prevalence of infection by 73 percent. (Source: The Carter Center)

Decades of global efforts have paid off,

and onchocerciasis is eliminated in more

than 75 percent of affected populations in

the Americas. Transmission only continues

in a remote area of the Amazon rainforest

on the Brazil/Venezuela border. In Africa,

where onchocerciasis is much more prevalent,

community-directed treatments are

beginning to show good results, reducing

the prevalence of infection by 73 percent. (Source: The Carter Center)

“Voice and Hands”

Ron Guderian and his wife, Eleanor Corey Guderian ’66, had been serving in Ecuador two years with mission organization Reach Beyond — formerly HCJB (“Heralding Christ Jesus’ Blessings”), named for the call letters of their radio station “Voice of the Andes.” It was the world’s first missionary radio station, and the first radio station in Ecuador to broadcast daily. With the goal of being the “voice and hands” of Jesus, the mission paired Christian radio broadcasts and medical care — two specialties that fit the Guderians’ talents.

Ron and Eleanor had met as students at Prairie Bible Institute, and both transferred to Seattle Pacific College to complete their degrees — hers in music and education, his in chemistry with a biology minor, where he first performed research. They married, and started a family while Ron pursued a doctorate at University of Washington in biochemistry and pathology, followed by a postdoctoral residency in clinical pathology and tropical medicine at University of California, San Francisco.

Trained in music and education at Seattle Pacific, Eleanor taught music, performed, and conducted choirs for radio broadcasts.

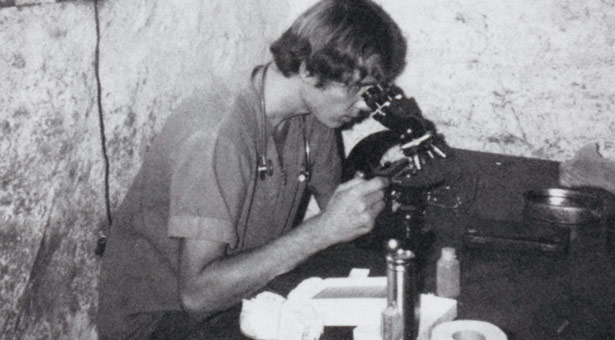

Ron Guderian at the microscope in a provisional rural

clinic.

Ron Guderian at the microscope in a provisional rural

clinic.

“I grew up in a family where missions was the highest calling you could have,” she recalls. Later moving into management and administration, she also participated in many other forms of ministry, including teaching the Bible, counseling, facilitating workshops, training, and developing leaders, not to mention caring for the three children they were raising, who were attending school in Quito. Eleanor went on to earn, through distance learning, both master’s and doctoral degrees in management.

“We did a number of things, even with the government, because HCJB was highly respected,” she says. “It didn’t make a difference that most people were Catholic and we were evangelicals. They considered HCJB radio their own.”

Ron, Eleanor, and their two oldest children left for language school in Costa Rica in 1974.

Ron, Eleanor, and their two oldest children left for language school in Costa Rica in 1974.

The mission also owned two hospitals, one in Shell, and one in Quito, where Ron’s work was based. With his background in research, he was tasked with setting up a pathology lab in Quito, as well as providing basic health care as part of a mobile medical unit.

“Our program started with a primary health care system, because there was no primary health care,” Ron says. Mobile medical teams would head out from the hospital into remote areas to treat patients and show films — both presentations of the gospel and public health films produced by Disney, translated into Spanish.

“Ron was kind of the Indiana Jones of HCJB,” says Harold Goerzen, senior editor at Reach Beyond. “He was kind of a loose cannon, in a way, with a flair for adventure.” Goerzen, a Canadian who lived in Ecuador at the time, recalls visiting Guderian at Hospital Vozandes in Quito and watching him, casually in conversation with a young Peace Corps volunteer, stick a pair of tweezers into the man’s neck and pull out a thick, white, inch-long worm, the larva of a botfly.

With the tribal leader’s question — “What are you going to do about it?” — on his mind, Guderian began to devote more of his time to documenting and researching incidences of the disease, though he continued to provide medical care.

“The only way river blindness could be eradicated would be by empowering the communities to take the drugs themselves.”

Initially, Ecuadorian health officials reacted with disbelief. After three years, they accepted his reports, and sent doctors out to the site to verify what Guderian had discovered. The good reputation of HCJB and Hospital Vozandes worked in his favor. He was asked by the health department to coordinate the national investigation of onchocerciasis.

“A lot of people had a respect for Ron’s professional work, and he had an opportunity to be a witness as well,” says Keith Isbell ’86, a missionary in Ecuador who, while he was an SPU student, spent two summers volunteering with Guderian’s river blindness work.

“Pray, pray, pray,” Guderian wrote home in a 1981 letter to supporters, “for wisdom in how to approach such a large project … For personnel, so that the project might be completed this year … For our protection from infection by the disease.”

Scientists on the Doorstep

Guderian and his team published their findings in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Publication turned out to be a significant step. Through the decades, he would co-author dozens of scientific papers (the latest one published this year), collaborating with researchers around the world, though perhaps he is proudest of co-authorship with the Ecuadorian researchers he helped train at Hospital Vozandes Quito. Of the Ecuadorian physicians who worked with him, he notes that 18 went on to study in the U.S., the U.K., Belgium, Brazil, Mexico, and France.

“We were able to get them grants and fellowships to study outside the country,” he says. “They all came back with either a master’s or a PhD, and they now are basically the ones running the whole program.”

Among readers of that 1982 paper was Frank Richards, who now heads the Global River Blindness Elimination Program, headquartered at Atlanta’s Carter Center. Richards still has his copy of Guderian’s article, complete with underlines and notes scribbled in the margins.

“Missionary physicians have played a very important role in tropical medicine,” Richards says. “So I wasn’t really that surprised that a missionary physician in the boonies, seeing patients, would happen to discover a previously unknown condition.”

Richards was not the only researcher who took note. One day around that time, Guderian recalls, he was called down to the hospital mission office and told, “There are two gentlemen here to speak with you.”

They were researchers from the prestigious London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who had read his papers — and they wanted to work with him.

In Guderian’s telling, partnerships like this seemed to happen when needed most, as answers to prayer. The Germany-based Christian Blind Mission provided financial support. The London School provided lab facilities for research. The Catholic archdiocese of Esmeraldas provided resources to develop community health infrastructure.

With funds from the Rotary Club, the Centro de Salud in Zapallo Grande was built in 1991 and continues to be a crucial part of the health care of the communities along the Rio Cayapas.

With funds from the Rotary Club, the Centro de Salud in Zapallo Grande was built in 1991 and continues to be a crucial part of the health care of the communities along the Rio Cayapas.

But one of the most dramatic partnerships and steps forward came in 1987 (the year Guderian was honored as Seattle Pacific University’s alumnus of the year for his medical mission work). That year, Merck Pharmaceuticals announced that it would make freely available the drug ivermectin, or Mectizan, for distribution in any country where river blindness was present, for as long as the disease persisted.

Discovered in the late 1970s, in a single microorganism from a soil sample taken from a Japanese golf course, the chemical compound ivermectin was turned into a drug at Merck’s laboratory. At first, veterinarians used it to kill parasites for animals such as dogs and dairy cows. But a 1982 trial with Senegalese river blindness patients showed improvement with almost no negative side effects. The treatment could kill the microfilariae and shorten the adult worms’ lifespan without further harming patients’ vision. Administered twice yearly, it would stop the disease.

William Foege, who headed the Carter Center at the time and helped set up the mass drug distribution program, says it was intentionally designed to make it as easy as possible for people to receive the medicine.

“It’s unique because there’s no superstructure — it’s down to the very slimmest network that’s required to make this work,” he says.

A country just had to develop a distribution plan, which Ecuador did, beginning in 1990. Three years later, Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas (OEPA) was launched, a public-private partnership among governments of the six affected countries, Merck, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Carter Center, and other NGOs. African countries formed a similar partnership. The scale was massive: In Ecuador alone, the Carter Center reported in 2008, 27,372 Mectizan treatments were administered to more than 16,000 people.

Guderian spent many years working in this health center. In Quininde, Guderian visited a clinic and laboratory run by a former student, Philip Cooper. Here, Cooper shows Guderian samples of parasitic worms that were recently collected from

participants in Cooper’s study

of early childhood health.

Guderian spent many years working in this health center. In Quininde, Guderian visited a clinic and laboratory run by a former student, Philip Cooper. Here, Cooper shows Guderian samples of parasitic worms that were recently collected from

participants in Cooper’s study

of early childhood health.

A Community-Led Effort

But how, exactly, do you get 16,000 people in tiny villages in a remote area of the Ecuadorian rainforest to take one pill, twice a year, for 18 years?

The real solution, Guderian emphasizes, came not from high-powered health organizations or wealthy institutions, but from the people. Two of the poorest and most marginalized groups in Ecuador, both the Afro-Ecuadorian and Chachi communities trusted each other more than they would trust outsiders who might sweep in twice a year, give out pills, and then leave. The only way river blindness could be eradicated would be by empowering the communities to take the drugs themselves.

In Zapallo Grande, Guderian greets Corina Nazareno and her granddaughter. As a young woman she was Guderian’s chief cook and housekeeper for many years.

In Zapallo Grande, Guderian greets Corina Nazareno and her granddaughter. As a young woman she was Guderian’s chief cook and housekeeper for many years.

From the beginning, Guderian was an advocate for running the program at the local level, by community members. He’d seen the value of putting people first, even making unlikely alliances with some traditional healers, or curanderos. Though he says curanderos’ practices and beliefs conflict both with Christianity and with Western medicine, he had seen the trust people invested in their healers.

“I just made a very specific goal — I don’t know if it was right or wrong — to make a friendship with the curanderos,” he says. “It broke down the barriers, but we didn’t lose our identity either. Christ was a radical person — he approached people with no fear, but there was no compromise on who he was, either.”

Networks of trust, built over the years, paid off. Trained by the Ecuadorian Ministry of Health, community health workers kept track of who had taken the medication, making sure that every person, sick or not, took the drug. With no bad side effects and quite a few good ones — killing scabies, lice, and intestinal worms — people saw they had a lot to gain from taking the twice-yearly dose. “This is a victory of these communities, by and large,” Richards says. “The hopes are that the communities will recognize this victory and move on to embracing other health challenges and community development challenges.”

That”s already happening in big ways and in small. At an international meeting of OEPA in Quito in 2013, Italian missionary doctor Mariela Anselmi, who has headed the community health efforts, flipped through PowerPoint slides highlighting all the other areas of health improvement since Mectizan drug distribution began.

Malnutrition in children under 5 years had dropped. Incidence of TB dropped, since people who had TB were taking their medicine. Yaws, a tropical skin infection, was eradicated. Malaria was almost nonexistent. Pregnant women were getting prenatal care, and maternal and neonatal mortality rates dropped.

“It’s a model program for programs worldwide,” says Phil Cooper, an Ecuador-based researcher with Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, who did his first fieldwork under Guderian in the late ’80s. “It’s very bottom up rather than top down, supported by Mariela’s group in Esmeraldas, but the local people decide priorities.”

Bearing Fruit

Guderian walks a path he knows well from the dock along the Río Cayapas to a guest house at the top of

the hill in San Miguel.

Guderian walks a path he knows well from the dock along the Río Cayapas to a guest house at the top of

the hill in San Miguel.

Ron and Eleanor left Ecuador in 1997, once their three children had all graduated from high school in Quito. Their Stanwood, Washington, home holds many mementoes of their time in Ecuador, including binders of all the letters and photos sent home over the years.

But, Ron maintained strong ties, both to Ecuador and to global health research. He now serves as a consultant to the WHO, helping to verify the progress made by river blindness eradication programs in other countries. The community-based treatment model that worked so well in Ecuador is now being established on the Brazil/Venezuela border, a remote Amazonian area inhabited by the Yanomami tribe, and the last place in the Americas where river blindness is still being transmitted.

With fond memories of trips into the jungle with their dad, the three Guderian children are all working in medical careers, including Jeff Guderian ’90, a researcher at Seattle’s Infectious Disease Research Institute.

On a recent trip up the Cayapas River, Ron reconnected with many friends and colleagues. Leaders had much good news to share. “We just came back from vaccinating all the children along the river,” one Chachi health worker reported.

“That’s better than in the U.S.!” Guderian says.

He also met with local pastor Felix Valencia, who leads a church school and a network of more than 50 churches along the river system, pastored by indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian leaders. Seeds of the gospel planted decades ago are bearing much fruit.

”Before, there were real divisions,” Guderian says. “Today we have an Indian pastor serving the black community, and a black pastor serving the Indian group.”

The community-led model, it seems, is effective at both spreading the gospel and spreading health care. More than anything, Guderian considers himself a witness to these communities’ efforts.

“It shows that this diseases can be controlled, if you work on a community level, and inspire people to take ownership,” he says. “And they deserve recognition. Every year for 18 years, making sure that everybody in their community was treated biannually, is an absolutely incredible feat. And they did it.”

Guderian joins the congregation of the Baptist Church

of Anchayacu during a service held in his honor. The

pastor of the church, Felix Valencia, has been a friend

of Guderian’s since 1982, and was the chaplain for

the doctor’s mobile health efforts in the communities

along the Río Cayapas. Guderian also helped raise

funds for churches and a school in Anchayacu that

bears his name.

Guderian joins the congregation of the Baptist Church

of Anchayacu during a service held in his honor. The

pastor of the church, Felix Valencia, has been a friend

of Guderian’s since 1982, and was the chaplain for

the doctor’s mobile health efforts in the communities

along the Río Cayapas. Guderian also helped raise

funds for churches and a school in Anchayacu that

bears his name.

Tropical Disease in the Classroom

Seattle Pacific students in “Clinical Microbiology” courses go in-depth when studying a disease such as onchocerciasis, says Associate Professor of Biology Derek Wood. They’ll study parasitology, epidemiology, distribution, transmission, and treatment — not to mention the cultural understanding needed for cross-cultural medical work.

“A lot of our students go to places where these diseases are prevalent, through SPRINT and medical mission trips,” Wood says. “It’s an important aspect of medicine, and that’s what I love about teaching here, is that our students are focused on service and getting out there in the world.”

Both the Matthew Kelley Medical Scholarship Endowment and the Joy Rusher and Lois Samuelson Scholarship Endowment provide scholarship support to students intending to pursue medical mission work. Want to support students in this field? Visit spu.edu/give. And learn more about SPU’s biology program at spu.edu/biology.