|

|

Spring 2007 | Volume 30, Number 1

| Books, Film & Music

|

|

|

Response onScreen

Conscience, Character, and Conviction: Amazing Grace and The Lives of Others

The spirit moves in mysterious ways. Sometimes, God changes our hearts through the inspiring testimony of a godly person. Sometimes he changes our hearts through the influence of conscience.

Two of 2007’s most celebrated films — Amazing Grace and The Lives of Others — tell stories about people caught in a crisis of conscience. In Amazing Grace, the passion of William Wilberforce inspires a whole nation to change its ways. And in The Lives of Others, one man experiences a change of heart while sitting alone in a dark room and spying on his neighbors.

Both stories could be summed up in that famous lyric penned by John Newton: “I once was blind, but now I see.”

Amazing Grace (Bristol Bay Productions)

Amazing Grace |

Michael Apted is a versatile director. He’s made movies such as Nell and Enigma, taken a turn with the James Bond franchise (The World Is Not Enough), and directed a few episodes of the television series Rome. Every seven years, he delivers a new installment in a series that Roger Ebert calls one of the greatest contributions to cinema — the “Up” series (7 Up, 14 Up, etc.).

But Apted has never directed anything quite like Amazing Grace, a lavish period piece that tells the story of William Wilberforce, and how his leadership brought about the abolition of slavery in England.

The film celebrates political courage without misleading us about the hardship suffered by those who strive to do the right thing. Wilberforce (1759–1833) suffered on several fronts as he stood like David before the Goliath of British Parliament, seeking to change their minds and hearts on the issues of slavery. Apted, working with a smart, sprightly script by Steven Knight (Dirty Pretty Things) gives sufficient time and attention to the complications of court proceedings. And we're left in no doubt that Wilberforce's convictions took a toll on his health.

The Scriptures say, “Where your treasure lies, there will your heart be also.” While Wilberforce may not have lived long enough to bask in the joy of his victories, it is clear that he strove with his eyes fixed upon heaven. He was only 21 when he was elected to the House of Commons, but his long battle against the slave trade ended only three days before his death. The burden that he bore physically, psychologically, and spiritually until the end — that’s the focus of the film.

In a season when filmmakers are rushing to get the attention of movie-going Christians, Apted has reminded us how to make an inspiring film about faith. How often do we see Christian faith portrayed without cynicism? And when Christians bring stories of faith to the screen, how often are they honest about the hardships and unanswered questions that come with the journey? Far too often, movies about Christians end up telling us that faith in God will make our lives happier and more successful. Wilberforce's story truly reflects the glory of Christ as we see him sacrificing so much to save others.

Amazing Grace does have a bit of a Hollywood glaze to it. The romance feels airbrushed to give the audience a more engaging story, and some of the courtroom antics feel a bit staged. The chronology of the film is a bit disorienting at times (flashbacks and "four years later" updates keep us on our toes). Nevertheless, it's remarkable how many characters have wit and personality in spite of their standard-issue period-piece costumes. Knight has enlivened what might have been dry and workmanlike, peppering the courtroom scenes with personality and verve, spicing the romance with wit, and spiking the punch of courtly language with just enough pizzazz.

And the cast brings the script to vivid life. Ioan Gruffudd may not have recommended himself for the part with his work in Fantastic Four, but he's surprisingly engaging here. While his courtroom speeches fall short of riveting, Gruffudd makes up for that by drawing us into the inner struggle of a man who fought formidable odds day after day.

As a romance, you could call this Love, Eventually. Romola Garai plays Barbara Spooner, who eventually marries Wilberforce, with charm and humor. Garai is a scene-stealer in everything she does — she proved herself a natural leading lady in I Capture the Castle, and she’ll be back onscreen soon in an adaptation of Ian McEwan’s Atonement, directed by Joe Wright (Pride and Prejudice).

But leave it to the veterans to steal the show. In every scene they're given, Michael Gambon and Albert Finney mop the floor with everyone else. As the great reverend John Newton, who penned the famous hymn of the title, Finney is fantastic. He’s onscreen for only a few minutes, but you’ll be talking about him after the movie. In one emotional moment, he utters one of the simplest, clearest, most moving Christian testimonies this moviegoer has ever seen. Just as memorable, Michael Gambon, so good at playing sinister villains, finds a lot of comedy in his own work as the sullen Lord Charles Fox.

While it can't quite reach the same spirited heights, Amazing Grace captures some of the spirit and showmanship that made Milos Forman's Amadeus such a classic. We learn a great deal about Wilberforce's interests and personality along the way, from his care for animals to his extravagant generosity to the poor. And while it's fair to say that too many films about the sufferings of Africans end up glorifying privileged white guys, Wilberforce's contribution to history is long overdue for a standing ovation. So that complaint should not prevent anyone from seeing this film.

The Lives of Others(Sony Pictures Classics)

It’s a tough story to tell in any context — the redemption of a monster. A storyteller who accepts this challenge faces formidable challenges:

• How do you convince the audience that a villainous creep is experiencing a change of heart?

• How do you manage to illustrate this without wrapping his transformation in sentimentality?

• How do you create a character so monstrous that we'll find his deeds repulsive, and yet so interesting that we’ll desire his redemption?

And then there's the complicated matter of the transformation itself. What triggers it?

The change should not happen too quickly. Damascus-road encounters do occur, but they’re rare, and difficult to portray convincingly. How do you illustrate an event so shattering that it changes a man, heart and soul, in a moment? No, it's much more possible to show an incremental change, because that is how most of us change ... in stages, through a long sequence of events.

The Live of Others |

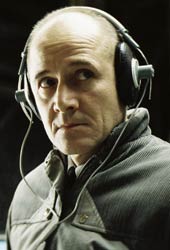

The Live of Others, which won an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, is about a monster named Gerard Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe) who lurks in East Germany, working as a surveillance officer for the Stasi forces during the mid-1980s. When Wiesler is appointed to secretly monitor every conversation in the apartment of a writer who may have anti-socialist sentiments, he finds that it's not quite so easy to resist the allure of his target’s convictions.

As Wiesler, Ulrich Mühe is fascinating. While he listens to the playwright, Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch), his actress girlfriend Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck), and their conspiratorial friends, his face is like a death mask, reminiscent of Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. But where Lecter was a monster, without a flicker of conscience, Wiesler seems feeble, sad, and thus, a person who might not yet be lost.

Like Hamlet's wretched uncle forced to watch a play that reveals his own wickedness, Wiesler begins to realize the darkness of his own empty life. To revise a line from Hamlet, “The play's the thing to catch the conscience of the surveillance officer.” However, in this case, the “play” is not a charade — it’s the true-life interaction of good men and women, which goes on daily while Wiesler watches from the shadows. Starved for light, he begins to long for the freedom and virtue that his “neighbors” are conspiring to defend. Ultimately, he must decide whether or not to crush the very thing he secretly cherishes.

In that sense, the film is about the divide between government and “the common people,” and how those who live insulated by walls of power and privilege may fall victim to delusions about the rest of the world. The film is also a fine testament to the power of art. As these government agents seek to ensnare the playwright before he delivers any truly subversive work, it is clear that they are driven by fear. But fear such as theirs grows from insecurity, from the knowledge that the truth will not support them in the end, whether they admit it to themselves or not.

But this is not primarily a political film. Director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck directs our attention to a central question: Can a selfish man learn to be selfless? If so, what brings that about? And where does such a reversal lead him? The answer is clear. But The Lives of Others illustrates it with only a dash of sentimentality, so that we have to face, along with Wiesler, the truth that integrity leads to vulnerability and sacrifice.

As I watched Wiesler listen to his headphones, surrounded by the instruments of voyeurism, we might be reminded of our own media-saturated culture, and how much of our time we spend “spying” on “the lives of others” — through film, television, and news media. Are we attending as closely as Wiesler? If so, what are we looking for? Evidence by which we can condemn the subjects and make ourselves feel superior? Or are we witnessing them with compassion and humility, open to seeing the truth and being transformed?

— BY Jeffrey Overstreet (jeffreyo@spu.edu)

Read past columns in Response OnScreen Archives.

Back to the top

Back to Books, Film, & Music Home

|

|

|

|

|