Exploring Chemistry and Creation

2010 Weter Lecture

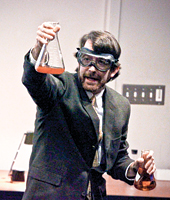

Safety goggles required: Associate Professor of Biochemistry Benjamin McFarland mixes science and Scripture. View his lecture and others at www.spu.edu/itunes. |

It’s a question that every science educator at a Christian school or university will be asked in the classroom: How do science and the biblical account of creation relate to one another?

Many educators might want to dodge that question. SPU faculty members never do. And certainly not Benjamin McFarland, associate professor of biochemistry at Seattle Pacific University. On the evening of Tuesday, February 2, in front of a standing-room-only audience in Demaray Hall 150, McFarland offered his answer in a high-energy lecture — complete with multimedia and a live chemistry experiment.

The 36th annual Winifred E. Weter Faculty Award Lecture, titled “The Chemical Constraints on Creation: Natural Theology and Narrative Resonance,” itself took the form of an “experiment.” McFarland used the methodology of “natural theology,” which aligns two pieces of knowledge — in this case Scripture and science — in order to see where their “shapes” are similar, where they “resonate.”

Organizing his lecture into seven “chemical songs” such as “From Heavy Atoms to Earth, starring ‘Gravity’” and “From Oxygen to Humans, starring ‘The Brain,’” McFarland laid out the sequential flow of what he called “the chemical story of creation,” noting how that story resonates with the Scriptural account of creation in surprising ways. For example, said McFarland, in the chemical story, from the moment of creation the laws of physics ordered the periodic table of the elements, which then ordered the behavior of chemicals throughout history. “This aligns with the poetic books of Scripture praising God for constraining chaos,” he said. “And when Jesus stilled the sea, he repeated his actions of billions of years earlier.”

Although the two accounts of creation may differ, McFarland argued, that doesn’t mean they contradict each other or that both stories can’t be true. The book of Genesis, he said, tells the story of creation through the lens of its own time, painting a picture for readers with a certain vocabulary and scientific understanding. Today, he continued, we speak differently, and we have different scientific tools. Nevertheless, when we put the latest scientific observations alongside the Genesis account, a rich dialogue and new understanding emerge.

“Because there is one Creator of one truth to know, fruitful interchange must be possible,” McFarland said. Not only are both stories true and reliable, they can also be “known through fair inquiry,” he continued, quoting Dallas Willard’s book Knowing Christ Today.

The continuing revelations of science do not force anyone to conclude that there is a creator, said the Weter lecturer. But they do make that conclusion possible — and even, in his opinion, likely. He argued that it is difficult to consider the chemical evolutionary process as arbitrary when we study the periodic table and the laws of thermodynamics — and the fact that they seem so carefully calibrated to enable life’s development. Those conditions, said McFarland, suggest that someone, somewhere, had a purpose

in mind.

“Knowing both stories,” McFarland said as he concluded the lecture, “one hears the Bible anew. God is a billion times more patient than we had dreamed, and all the more ingenious to hide life in a handful of elements.”

—Photo by GIna Volpe/The Falcon

Return to top

Back to Campus Home

|