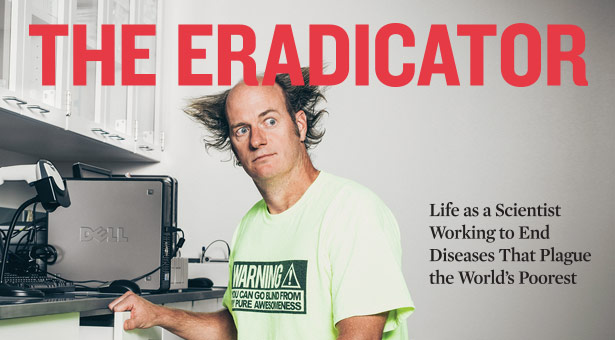

Although Jeff Guderian doesn’t normally sport “mad scientist hair” at work, he hopes his former classmates will see that he hasn’t changed since his days at SPU, when, he admits, “goofy hair was a regular occurrence.”

Although Jeff Guderian doesn’t normally sport “mad scientist hair” at work, he hopes his former classmates will see that he hasn’t changed since his days at SPU, when, he admits, “goofy hair was a regular occurrence.”

By Jeff Guderian ’90 | Photos by John Keatley

Jeff Guderian ’90 has a history with tropical disease.

He is a research associate at the Infectious Disease Research Institute, one of the nonprofit organizations headquartered in Seattle’s global health hub. He’s also the son of missionaries Eleanor Corey Guderian ’66 and Ron Guderian ’67, a medical doctor and Seattle Pacific University’s 1987 Alumnus of the Year.

Ron has researched onchocerciasis, or river blindness — a disease transmitted by blackfly bites that is the second most common infectious cause of blindness in the world — since he first discovered it in the rainforests of Ecuador in 1976. Because of his work, and subsequently developed treatment, the World Health Organization will soon declare river blindness eliminated from Ecuador.

While his father is seeing the results of his life’s work, Jeff carries on the tradition of working to eradicate deadly disease — in a Seattle lab. He recently traveled from the Northwest to Brazil, where he presented IDRI’s research to the Fifth World Congress on Leishmaniasis. A disease transmitted through sandfly bites, its visceral form is fatal if untreated.

You can find Jeff Guderian’s name as co-author on dozens of papers about diseases and their potential cures. He says his work as a scientist connects to his childhood on the mission field:

You could say I’ve been involved in neglected tropical diseases and public health since grade school. I was 6 years old when we moved to Quito, Ecuador, where my dad, a medical pathologist, was put in charge of doing mobile medical care for a local hospital. Using a medically equipped van, he and his crew would go to the rural areas of Ecuador to do public health. During the day they would see patients, and at night they’d show reel-to-reel Disney health videos in Spanish, followed by a gospel message by the local pastor.

I would accompany dad on these trips whenever I could.

Dad always took his camera with him to document the way disease presented itself on patients, and one time I remember sneaking downstairs to watch him review the slides, only to receive a warning not to look at them.

“Too gross; too disgusting,” he said. But come on! What 9-year-old boy isn’t interested in looking at gross and disgusting things? One of the slides showed a massive facial ulcer on a patient with mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, and my curiosity switched to intrigue. That image has stayed in my mind ever since.

After graduating from high school, I decided to attend SPU, my parents’ alma mater. I began as an electrical engineering student, but shortly switched to biology.

During my junior year I heard about Seattle Biomedical Research Institute from a classmate who was doing an internship there. (Back then, the Institute was on Nickerson Street, right across from 7-Eleven — a nice short walking distance!) He recommended I do the same. So I got a work-study position, initially washing glassware and making solutions.

During the following summer and my senior year, I was given a rotational internship with several principal investigators, including Steven Reed, who later founded Infectious Disease Research Institute. He spent a portion of his career in Brazil studying leishmaniasis and Chagas disease, both of which my dad had come across in Ecuador. Because of this coincidence, after graduating from SPU, I decided to continue working for Steve Reed. I found it very personally rewarding to, in effect, work on the same diseases my dad did in Ecuador.

I have gotten a fantastic on-the-job education in tropical disease working at IDRI. Because I have been here for a while, I have been trusted with many responsibilities in several projects. During a typical day, I do a little bit of everything: I’m in the lab; I’m in meetings; I’m dialoguing with other scientists, all the while making sure things are proceeding smoothly.

IDRI sees itself as a “nonprofit company.” Similar to academic institutions, our survival is dependent on donations, grants, and contracts; but in addition to publishing our research, we develop products (vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and adjuvants) to directly help those afflicted with the diseases we research. “Even though it’s exciting, it can be frustrating,” Curt Malloy, our senior vice president of operations, said to me once, “because building IDRI is like remodeling a plane while it is in flight.”

I have worked on many diseases during my 21-and-a-half years at IDRI, and I am pleased that my current work is primarily vaccine development for leishmaniasis. I can still see the horribly disfigured face of the Ecuadorian afflicted with leishmaniasis in that picture slide so long ago. And I am grateful that I have the opportunity to be involved in critical research that will help those like him.