Charles Ethan Porter: Tenderness and Tragedy

An overlooked American master of still life painting

By Katie Kresser, Associate Professor of Art

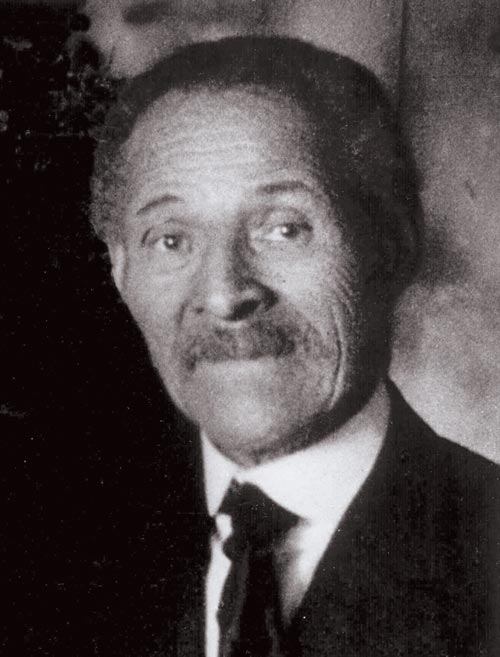

Charles Ethan Porter (1847–1923) was born to a free African-American family in Hartford, Connecticut. Porter and his family were proud of their heritage and well-connected in the New England abolitionist community, but they were nevertheless almost cripplingly poor. Porter’s father was probably a mill worker, and Porter’s mother was an itinerant housekeeper. Porter himself had to do years of hard labor in order to pay his way through school. And like many 19th-century families, the Porters were no strangers to tragedy. Before Charles reached adulthood, the family had lost eight children to sickness or war.

Charles Ethan Porter, however, was a focus of pride and celebration in his community. Hailed as an artistic prodigy, he became the first African-American admitted to the prestigious National Academy of Design, and he earned the attention of prominent benefactors such as Frederic Edwin Church (for a time America’s most famous artist), Connecticut Governor Joseph Hawley, and the author Mark Twain.

Fiercely determined and buoyed by community and national support, Porter later took the bold step of enrolling at the Académie Julian in Paris, where he studied with some of the most globally prominent artists of the age. Porter was probably the first African-American to undertake such a venture, and the effort required tremendous sacrifice: great expense, greater homesickness, and considerable social alienation — as an African-American and devout Methodist, Porter struggled to integrate into Parisian society. But such was Porter’s ambition that he remained in Paris for over two years, absorbing the latest Impressionist techniques and adapting them to his meditative style.

Indeed, “meditative” is perhaps the best word to describe Porter’s works. Even during his days as a youthful prodigy, Porter made paintings so focused, so spare, and yet so detailed that they moved viewers to quiet wonder. He painted tiny insects against pure white backgrounds in a manner so delicate and ethereal that they seemed plucked from a dream.

With these paintings, Porter joined a stream of American “nature mystics” who, rejecting the heroic themes of European art, sought to capture the soul of the flora and fauna around them. Later in his career, Porter remained devoted to the small and fragile. His best-loved paintings are of flowers, fruits, and vegetables captured in almost crystalline stillness. This surely reflects Porter’s native tenderness: committed to his family and religiously devout, Porter was a gentle spirit who loved music (he was a church soloist) and who settled near his childhood home.

Porter’s later career did not, alas, fulfill the promise of its beginning. In the years immediately following the Civil War, African-Americans experienced discriminatory backlash in both North and South, and Porter was no exception. His prominent supporters abandoned him, his artworks failed to sell, and his (largely white) community tired of lending him financial support. It is rumored that Porter was reduced to peddling door to door, and when clients did not buy his paintings, they bought his labor instead. Toward the very end of his life, Porter’s faculties began to fail and his artwork suffered — but not before he produced dozens of beautiful canvases now in high demand.

Today, Porter’s works can be seen in numerous prominent institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and now, Seattle Pacific University.