|

|

Spring 2007 | Volume 30, Number 1

| Features

|

|

|

"Biblically Illiterate" continued

The Controversy Over Biblical Education

Studies show that Bible reading is not becoming more popular. But interest in biblical ignorance and its consequences is increasing.

Christian Smith, keynote speaker for Seattle Pacific University’s Day of Common Learning in October 2005, is the principal investigator for the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR) at The University of Notre Dame. His book Soul Searching gives a sobering look at religious ignorance among American teens.

The NSYR’s 2003 “first-wave” survey examined the Bible-reading habits of 13–17-year-olds. Forty-one percent of those teens never read the Bible, Smith says.

His findings are consistent with those of The Bible Literacy Project, another prominent effort to research the problem of biblical illiteracy and encourage change. A non-partisan, non-profit organization “dedicated to research and public education on the academic study of the Bible in public and private schools,” the Project has pursued two lines of inquiry. His findings are consistent with those of The Bible Literacy Project, another prominent effort to research the problem of biblical illiteracy and encourage change. A non-partisan, non-profit organization “dedicated to research and public education on the academic study of the Bible in public and private schools,” the Project has pursued two lines of inquiry.

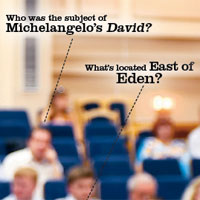

In their first report, the Project analyzed a Gallup survey that polled American public school students between the ages of 13 and 18, asking them what they know about the Bible and other religious literature. Two-thirds of the teens surveyed did not know that Damascus was where the apostle Paul encountered a blinding vision of Jesus. Was David ever king of the Jews? “No,” said 25 percent of them. Eight percent thought that Moses was “one of the 12 apostles.” Christian teenagers scored only a few points better than non-Christians.

For their second report, published in January 2006, the Project asked educators, “Is the Bible an essential part of education?” The overwhelming response, from 39 English professors belonging to 34 of the nation’s leading colleges and universities: “Yes.” George P. Landow of Brown University summarized the prevailing view when he said that an education without study of the Bible is “like using a dictionary with one-third of the words removed.”

The Bible Literacy Project also published a textbook — The Bible and Its Influence (BLP Publishing, 2005). Editors Cullen Schippe and Chuck Stetson guide readers through the various writings compiled in the Bible and examine how it has affected every conceivable area of culture. The textbook, they say, is not designed to proselytize, but rather to give students an objective presentation of the Bible’s content.

In its first year, the textbook is being successfully used in 83 school districts in 30 states. The Bible Literacy Project reports indications for extreme growth in the book’s second year. But, the idea of academic study of the Bible in public schools has vocal opponents, including Americans United for the Separation of Church and State.

The Bible as Foundation (and Fault Line) of American History and Culture

So what are the challenges facing students of American history, art, or literature who do not have lessons about the Bible?

The genesis of American history has everything to do with a dispute over who could speak authoritatively about the Bible. The invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century led to the production of differing Bible translations. Setting the Reformation in motion, Martin Luther was driven by a compulsion to give people access to the Bible, and the chance to read it in their own vernacular. That endeavor became the foundation of education in America, which achieved impressive success in teaching students to read so that they could read the Bible and establish it as the backbone of society.

It was religious persecution that drove the Pilgrims to sail for the New World. Puritan efforts to escape oppression gave rise to the idea of a “promised land,” reflecting the biblical story of the Israelites. The agnostic and skeptic Thomas Paine counted on the Biblical literacy of his audience when, in his pamphlet titled Common Sense, he denounced not only the British monarchy, but the idea of monarchy itself: “[F]or the will of the Almighty, as declared by Gideon and the prophet Samuel, expressly disapproves of government by kings.”

Later, the speeches of Abraham Lincoln, which helped to abolish slavery in America, relied heavily on the Bible. “[It] is the best gift God has given to man,” he said. “But for it we could not know right from wrong. All things most desirable for man’s welfare, here and hereafter, are to be found portrayed in it.” Presidents and public figures have followed his example ever since –– including Martin Luther King Jr., whose “I Have a Dream” speech is fueled by scriptural references.

Beyond history and politics, what are biblically illiterate students to make of classic art? “The Great Codes of Art” — that’s what William Blake, poet and painter, called the Old and New Testaments.

Frederica Matthewes-Green, who has written for The Washington Post, Christianity Today, and The National Review, and published several books on Christian faith, is dismayed to see students lacking exposure to the source of so much artistic inspiration. “Their ability to appreciate the architecture of an ancient cathedral, or to ponder the meaning of a Bach chorale … is thus truncated. Biblical literacy matters because it is the key to understanding every form of Western art.”

And what do drama students grasp when Hamlet compares himself to Abraham and Isaac? What would John Steinbeck think if someone asked him about the title The Grapes of Wrath? Will readers know why J. Alfred Prufrock calls himself “Lazarus” in T.S. Eliot’s landmark poem, or recognize the importance of Absalom in Alan Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country?

Similarly, whether audiences are watching Apocalypse Now, The Matrix, Superman Returns, or a recent fantasy movie about a Christ-like lion, they can find cinematic allusions to the Bible. In 2006 alone, three prominent movies — Little Children, Children of Men, and Babel — took their suggestive titles from the Bible.

Nevertheless, the subject of Scripture has become a minefield for teachers and students. Some believe that speaking of the Bible in public school classrooms violates the separation of church and state. Others argue that there is no reference to such a separation in the Bill of Rights, and that the founding fathers never intended one.

In any case, it is clear that those who imagined a nation distinguished by religious freedom would neverhave envisioned a population plagued by biblical illiteracy.

Back | Next Page 2 of 3

Back to the top

Back to Features Home

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

from the president

Embracing the Christian Story

SPU President Philip Eaton asks what would happen if the Bible were at the center of the learning enterprise.

campus

Destination: Asia

SPU President Philip Eaton joined a historic delegation of U.S. university presidents that visited Asia.

alumni

Coffee as Change Agent?

Pura Vida employees, including several SPU alumni, engage the culture using a social-venture business model.

books, film, & music

Dark Alphabet

Jennifer Maier, poet and SPU associate professor of English, receives a literary award for her first book.

athletics

National Tournament Returns

For the first time in 10 years, SPU hosts the USA Gymnastics Women's Collegiate Championship.

my response

Undone by the Word

Response writer Kathy Henning shares her journey to know the Bible better.

Response art

Pink Emperors

Class of 1973 alumna Jill Ingram introduces Response readers to “Pink Emperors.”

|

|

|

|