by Joseph Pearce

Illustrations by

For more books

about Tolkien

David Wyatt

![]()

see bottom of page!

As J.R.R. Tolkien fans awaited the December

opening

of the film The Lord of the Rings, Seattle Pacific University's C.S.

Lewis

Institute hosted a special conference to explore the epic's place in 20th

century

literature and culture. "Celebrating Middle Earth: The Lord of the

Rings

as a Defense of Western Civilization" attracted 600 people to campus

November 9-10

to hear presentations by Tolkien biographer Joseph Pearce, author Peter

Kreeft,

and SPU faculty members John West, Janet Blumberg, Phillip Goggans and Kerry

Dearborn.

Also on the program were a medieval banquet and a performance of

The Lord of the Rings Symphony by the SPU Symphonic Wind Ensemble.

"When I heard about the new film version of The Lord of the Rings,"

says

John West, associate professor of political science and conference

organizer, "I

thought it would provide a wonderful opportunity to explore the theological

and

ethical dimensions of Tolkien's saga. I was also reading Joseph Pearce's

biography

of Tolkien at the time, and I thought it was so insightful that I wanted to

invite

him to SPU."

Pearce, whose book Tolkien, Man and Myth was published in 1998, spoke

about

the Christian foundation of The Lord of the Rings. "Far from being an

escapist fantasy," he told his audience, "The Lord of the Rings is a

theological thriller." Included below is an edited version of his remarks.

Tolkien and other British Christian authors have been the subjects of study

at

the Seattle Pacific C.S. Lewis Institute for more than 25 years. Today the

Institute

is a joint project of SPU's

Society of Fellows and

the Discovery

Institute.

The November conference was co-sponsored by the Intercollegiate Studies

Institute,

which provided funding for the event, as did the Eahart Foundation.

![]()

J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord

of the Rings has emerged as "the greatest book of the twentieth

century" in several major polls conducted in Britain in recent years. In one

poll of more than 25,000 bibliophiles, conducted by a major bookselling

chain and a national television channel, one-fifth nominated The Lord of

the Rings as their first choice. It was a runaway winner, securing 1,200

votes more than George Orwell's 1984, its nearest rival.

Many literary experts greeted Tolkien's triumph with contempt.

British writer Howard Jacobson dismissed Tolkien as being "for children

… or

the adult slow." Susan Jeffreys, writing in the Sunday Times,

described The

Lord of the Rings as "a horrible artifact" and added that it was

"depressing …

that the votes for the world's best 20th-century book should have come from

those

burrowing an escape into a non-existent world." Rarely has the cultural

schism

between the literati and the reading public been highlighted to such an

extent.

Most of those who sneered at The Lord of the Rings are outspoken

champions

of cultural deconstruction and moral relativism. They would likely treat the

Christian

beliefs of Tolkien with the same disdain as they have his writings.

But then some of Tolkien's critics are Christians. They remain suspicious of

The Lord

of the Rings because they see within its mythological setting hints of

neo-paganism,

possibly even Satanism. Can anything containing wizards, elves, sorcery and

magic

be trusted? Certainly, in the wake of the worldwide success of the Harry

Potter

books, many Christians fear the effect that fantasy literature might be

having on

their children. Are these fears justified? Should Christian parents prohibit

their

children from reading The Lord of the Rings?

I believe the answer to this question is an emphatic "no." Far from being

prohibited,

Tolkien's epic should be required reading in every Christian family. It

should take

its place beside the Narnian chronicles of C.S. Lewis (Tolkien's great

friend) and

the fairy stories of George Macdonald as an indispensable part of childhood.

The profoundly Christian nature of Tolkien's work can be seen by looking

more

closely at Tolkien the man, at his philosophy of myth, and at the particular

myth

he weaves so beautifully in The Silmarillion and The Lord of the

Rings.

Tolkien the Man

Tolkien was born in 1892. His father died in 1896, so Tolkien barely

remembered

him. His mother died in 1904, when Tolkien was only 12. Following his

mother's

death, he and his brother were sent to live with a distant relative, where

they

never really felt at home.

In 1916, within weeks of his marriage, Tolkien went off to fight in the

First

World War and was involved in the Battle of the Somme, one of the war's

bloodiest

conflicts. Tolkien referred to this battle when speaking of the "animal

horror"

of trench warfare. When people accuse Tolkien of escapism, they should

consider

the stark reality he lived through as both an orphan and a soldier.

Raised as a Roman Catholic, Tolkien had four children, and his role as

father was

crucial to his becoming a writer. He wanted to entertain his children, and

this

was the motivation for writing The Hobbit, the children's story that

became a bestseller and established Tolkien's reputation as a writer.

Among the biographical facts that Tolkien admitted were significant to his

works

were his upbringing in a "pre-mechanical" age and his academic vocation as a

philologist at Oxford University. His "taste in languages," he said, was

"obviously

a large ingredient in The Lord of the Rings."

However, it was his Christian faith that Tolkien said was the single most

important

influence on his writing of The Lord of the Rings. Indeed, it would

be a

mistake to see Tolkien's grand story as anything other than a specifically

Christian myth.

Tolkien's Philosophy of Myth

This paradoxical philosophy was destined to have a profound influence on the

non-believer C.S. Lewis. In September 1931, Lewis, Tolkien and their mutual

friend

Hugo Dyson walked together and discussed the nature and purpose of myth.

Lewis

explained that he felt the power of myths, but that they were ultimately

"lies

and therefore worthless, even though breathed through silver." Tolkien

argued

that we have come from God, and the myths woven by us, though they contain

error, reflect a splintered fragment of God's eternal truth.

Building on this philosophy of myth, Tolkien and Dyson went on to express

their

belief that the story of Christ was simply a true myth, a myth that really

happened.

God, the omnipotent Poet, told the True Story with facts, weaving his tale

with

the actions of real men in actual history.

Tolkien's arguments had an indelible effect on Lewis, and the foundations of

his

Christian faith were laid. It is interesting — indeed astonishing

—

to note that without J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis might not have come to be

known

and loved throughout the world as the formidable Christian apologist and

author

of such sublime Christian myths as The Lion, the Witch and the

Wardrobe.

Integral to Tolkien's philosophy of myth was his belief that the gift of

creativity

was a mark of God's divine image in man. Only God could bring something into

being

out of nothing. Man, however, could sub-create by molding the material of

Creation

into works of beauty, including art, music and literature.

The True Myth

Tolkien's own version of the Creation bears a remarkable similarity to the

Creation

story in the book of Genesis. In the beginning was Eru, the One, who "made

first

the Ainur, the Holy Ones, that were the offspring of his thought, and they

were

with him before aught else was made." Eru then allows the Holy Ones, or

archangels,

to share his creative gifts, and they bring forth the Creation of God as a

symphony

of praise in his honor.

Disharmony is brought into the cosmic symphony of Creation when one of the

archangels

decides to play his own tune in defiance of the will of the Composer. This

disharmony

is the beginning of evil. The rebel archangel is named Melkor, later known

as Morgoth,

and is obviously Middle Earth's equivalent of Satan. Shortly after

describing Melkor,

Tolkien introduces Sauron, the Dark Lord in The Lord of the Rings.

Sauron

is described as a "spirit" and as the "greatest" of Satan's servants.

The magnificence of Tolkien's mythological vision in The Lord of the

Rings

precludes an adequate appraisal, in an essay of this length, of the

Christian theology

that gives it life. In the impenetrable blackness of the Dark Lord and his

abysmal

servants, the ring-wraiths, we feel the objective reality of evil. In the

reluctant

heroism of the hobbits we see goodness and courage ennobled by humility. In

Gandalf,

we see a powerful — at times almost Christ-like — prophet who

beholds

a vision of the Kingdom beyond the understanding of men. In the true, though

exiled,

Kingship of Aragorn, we see glimmers of the hope for a restoration of truly

ordained

authority. In Boromir, we see the human capability for repentance and the

promise

of redemption.

Ultimately, The Lord of the Rings is a mystical Passion Play. The

carrying

of the Ring — the emblem of sin — is the carrying of the Cross.

The

mythological Quest is a veritable Via Dolorosa, or road to the Cross.

Many have failed to grasp this ultimate truth at the heart of Tolkien's

myth.

But one is reminded of the words of C.S. Lewis that a diligent atheist or,

for

that matter, a delicate agnostic, cannot be too careful of what he or she

reads.

In straying deeply into Tolkien's world, people will find a world of truths

not

previously perceived. And they might even come to see that the exciting

truths point

to the most exciting Truth of all.

Tolkien's Sources

While Tolkien drew on sources as old and varied as the Norse sagas, Homer

and the

Bible, his most fascinating influences came from the two bodies of

literature

that were the focus of his scholarly career. These were both English,

Medieval and

Christian, and grew out of periods of conversion and revival.

The first was Anglo-Saxon poetry (AD 600-1000), which Tolkien describes in

"Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics" as containing "an instinctive

historical

sense" from which its sadness and beauty chiefly derived. Lovers of riddle,

hero

tale and elegy, Anglo-Saxon poets represented Christ as the young

battle-leader

who died and was mourned by his followers despite his defeat.

But Tolkien also drew upon High Medieval chivalric works such as The

Pearl

and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, fourteenth-century poems that

reflected

the synthesis of Aquinas and Dante with their highly ordered European

Christian

vision of all things consummating in the eternal Heavenly Rose.

While Tolkien borrowed from the later chivalric worldview for his histories

and

characters, he set his tale deliberately within the darker Anglo-Saxon

elegiac

worldview, in which one is forced to choose the Good, regardless of whether

or

not that side will ultimately win out. Tolkien, like C. S. Lewis, saw great

danger

to Christianity if believers accepted the gospel in order to be on the

winning

side, leading to hedonistic selfishness, the antithesis of spirituality.

Only loving

the Good, even in its defeat, is true loyalty to Christ.

Tolkien and Lewis, Scholars and

Friends

As Joseph Pearce points out in his essay above, J.R.R. Tolkien helped

introduce

his friend and fellow Oxford scholar C.S. Lewis to Christ, thereby making

possible

Lewis' prolific career as a champion of "Mere Christianity."

But Tolkien benefited from Lewis's friendship as well.

Wracked by self-doubt, Tolkien probably never would have finished The

Lord of

the Rings without the faithful encouragement of Lewis, who was the

story's

chief booster during the more than a decade that it took Tolkien to write

his epic.

Tolkien would read parts of his developing story to Lewis, and Lewis would

respond

with criticism, praise, and even tears. Lewis also held Tolkien accountable.

In 1944,

Tolkien wrote that Lewis was "putting the screw on me to finish" the story.

Even

so, it would take Tolkien another five years!

After Tolkien achieved international acclaim from The Lord of the

Rings,

he wrote a correspondent that "I have never had much confidence in my own

work,

and even now when I am assured — much to my grateful surprise —

that

it has value for other people, I feel diffident, reluctant as it were to

expose

my world of imagination to possibly contemptuous eyes and ears."

According to Tolkien, it was Lewis who convinced him The Lord of the

Rings

was worth publishing and who kept him going during hard times. "Only by

support

and friendship did I ever struggle to the end of the labour," Tolkien wrote.

What an incredible testimony to the power of a friend's encouragement.

A Student's Review of the

Film

The transition from a book to a movie often ends in disappointment. The

producer

of The Lord of the Rings faced the challenge of adequately condensing

the

trilogy to make three movies of reasonable length while maintaining a

cohesive

storyline. Since the storyline is immense, misrepresentation seemed

inevitable.

Although the writer and director took some artistic license — such as

with

the omission of Tom Bombadil and the overemphasis of the elf princess

Arwen's role

as a warrior and as Aragorn's lover — these changes did not detract

from

the overall experience for me. I found the film version of The Fellowship

of

the Ring to have been surprisingly well done, and it captured two of the

major

themes in the tale: duty and friendship.

A strong sense of duty permeates Tolkien's epic. I think the movie correctly

portrays Frodo's reluctance to bear the ring and his ability to overcome a

sense

of inadequacy in order to fulfill his duty. Within The Fellowship it is

understood

that individuals are important, yet there are greater ideals worthy of

personal

sacrifice to attain. In this light, death is never in vain and can be noble,

as

in the case of Boromir.

Tolkien also had a high regard for companionship and friendship. The Lord

of

the Rings shows how the weaknesses of one can be supplemented by the

strengths

of another. Even though Frodo is inadequate to carry his burden, his eight

friends

come beside him and make his journey possible.

Despite the changes and necessary condensing, I think Tolkien's true vision

for

The Fellowship of the Ring was preserved in the film.

Tolkien was suspicious of paying too much attention to biographical details

about

the author in deciding whether a book was good or bad, and for the most part

I

agree with him. Nonetheless, Tolkien couldn't have written The Lord of

the Flies

any more than William Golding could have written The Lord of the

Rings.

Obviously, there is some profound correlation between an author and his

work.

Tolkien's philosophy of myth derives directly from his Christian faith. He

understood

the nature of myth in a manner that has not always been appreciated by

critics and

readers. For many people, a myth is merely another word for a lie, something

that

is intrinsically not true. For Tolkien, myth had virtually the

opposite

meaning. It was the only way that certain transcendent truths could be

expressed

in intelligible form.

Tolkien's last and unfinished work, The Silmarillion, forms the

theological

foundation and mythological framework for The Lord of the Rings. And

the

Creation myth in The Silmarillion is perhaps the most significant and

most

beautiful of all Tolkien's work.

Joseph Pearce is the author of a number of books, including Tolkien,

Man and Myth:

A Literary Life; Solzhenitsyn: A Soul in Exile; Wisdom and Innocence (a

biography of

G.K. Chesterton); and Literary Converts (a book about the spiritual

lives

of Waugh, Muggeridge, Lewis, Chesterton, Sayers and other British

writers).

He is currently co-editor of the St. Austin Review and

writer-in-residence

at Ave Maria College in Michigan.

Joseph Pearce is the author of a number of books, including Tolkien,

Man and Myth:

A Literary Life; Solzhenitsyn: A Soul in Exile; Wisdom and Innocence (a

biography of

G.K. Chesterton); and Literary Converts (a book about the spiritual

lives

of Waugh, Muggeridge, Lewis, Chesterton, Sayers and other British

writers).

He is currently co-editor of the St. Austin Review and

writer-in-residence

at Ave Maria College in Michigan.

More About Tolkien

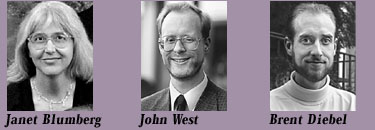

By Janet Blumberg, Professor of English

By John West, Associate Professor of Political Science

By Brent Diebel, Senior Philosophy Major

![]()

| Please read our

disclaimer.

Send any questions, comments or correspondence about Response to jgilnett@spu.edu or call 206-281-2051. Copyright © 2003 University Communications, Seattle Pacific University.

Seattle Pacific University |