Constitution Day 2009

President Lincoln’s Constitution and the Case Against Secession

By William Woodward, Ph.D.

Professor of History

Seattle Pacific University

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, is the momentous issue of civil war. ... You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to “preserve, protect, and defend it.”

–Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, 1861

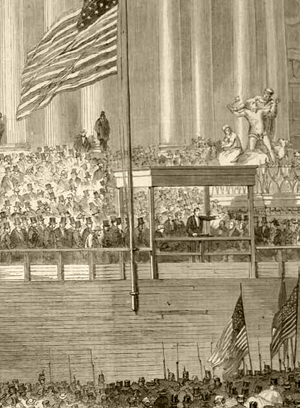

After speaking these ominous sentences, Abraham Lincoln took the presidential oath of office as prescribed in the U.S. Constitution. The chill wind and clouded sky thickened the mood in the nation’s capitol that fourth of March 1861. Perhaps no presidential inaugural in American history has been so freighted with foreboding.

After speaking these ominous sentences, Abraham Lincoln took the presidential oath of office as prescribed in the U.S. Constitution. The chill wind and clouded sky thickened the mood in the nation’s capitol that fourth of March 1861. Perhaps no presidential inaugural in American history has been so freighted with foreboding.

The seasoned lawyer and one-term congressman was now the laughably inexperienced chief executive of a distinctly “Disunited States.”

Seven of the erstwhile 34 had already submitted their resignations, as it were, and joined to proclaim a new Confederate States of America. How would this political novice respond to the South’s confident assertion of its constitutional right to secede?

Simply put, Lincoln would indeed fulfill that oath and preserve that Constitution by vigorously denying that it included any authorization — expressed or implied — for leaving the federal union. From the constitutional clash came, as Lincoln clearly stated, a cataclysmic Civil War. The storied Constitution of the United States would survive this, its most perilous hour, because of the man who so respected it and now determined to defend it.

Transforming the Union

In preserving the Union, in argument and ultimately in blood, Lincoln transformed it. Specifically, he made the Union — never before so strong — a nation. And he made the presidency — never intended to be so pivotal — an office of previously unimagined power.

Lincoln insisted his actions were contemplated and constrained by the Constitution itself. If the people’s Constitution, which limits the power of the government, comes under mortal threat, that government can and must, in the name of that people, stretch its power to meet that threat.

How comfortable are you with that bald claim on this Constitution Day 2009, in the bicentennial year of Lincoln’s birth?

For again we pause to ponder Lincoln’s understanding and use of the Constitution. A year ago, I focused on lawyer Lincoln’s constitutional argument against slavery in the years before his run for the presidency. It is now timely to examine how the newly elected president dealt with the great constitutional challenge posed by the secession of the Southern states — an episode whose sesquicentennial we mark next year.

As it turned out, the Civil War settled the most fundamental unanswered question about the Constitution. The American federal system divided “sovereignty” (or ultimate independent identity) between state and national government. But in a contest between the two, which had the final say?

South and North had long held “contrasting constitutional visions” on this point, in the phrase of legal scholar Daniel Farber. The South argued for the right to leave; the North for the impossibility of leaving. The differences deteriorated into bloody war. Abstract questions of constitutional theory had immense practical consequences.

(They still do. As recently as the 1990s, the U.S. Supreme Court split over whether states retained sovereignty to impose term limits on their representatives in Congress.)

So the task at hand is to connect constitutional theory to political power — to its locus, its uses and its limits — in the hour of America’s greatest crisis. We shall learn that the great charter signed on September 17, 1787, found, in the secession winter of 1860–61, its staunchest advocate and most adroit handler in the person of Abraham Lincoln.

The Case for Secession: The Power of Theory

How could the Southern states legally justify withdrawing or “seceding” from the United States? Their reasons went deep into the past, into the dark suspicions of central power long harbored by many Americans.

Recall that Americans had declared independence on the grounds that Britain had abused its power. So an independent United States, when it set up (constituted) its government, took pains to impose limits on that government.

A generation after the Revolution, the brilliant senator from South Carolina, John C. Calhoun, crafted an ingenious if self-serving interpretation of the Federal Constitution. It was the still-sovereign states, he argued, that held the final say on whether the national government was conforming to the limits prescribed in the Constitution.

Wait a minute, Mr. Calhoun. Didn’t the Constitution establish the national government over the states? And doesn’t the U.S. Supreme Court have the final say on what is permissible — and what’s “unconstitutional” — under the Constitution?

Well, yes and no, argued the artful South Carolinian. The “constitution was made by the States,” he asserted. What they did was voluntarily join a compact, an association or (in his words) a “union of the States, in which the several States still retain their sovereignty.” So long as they stayed in the Union, they bound themselves within the system. This view implied, of course, that they might not stay.

Here’s a way to grasp Calhoun’s position. Have you ever noticed, among your various online communities today, that sometimes you can “opt in,” and sometimes you have to “opt out”? Calhoun would understand that part of 21st-century culture. The states opted in to the Constitution, he believed. Accordingly, if they felt they could or should go it alone, they could later opt out.

To opt out of the United States back in the 1800s was to “secede.”

And why might that occur? Southerners warned that if the North came to so dominate the government that they would meddle with the South’s “peculiar institution,” slavery, they must bail out of the compact. Which returns us to 1860, the year Abraham Lincoln was elected president almost exclusively by the votes of Northerners. Once Lincoln’s victory was confirmed, the states of the deep South feared a “Black Republican” administration would attack their treasured system of human bondage. Not waiting until Lincoln assumed the presidency, they proclaimed their secession from the federal compact — led by (no surprise here) South Carolina.

And the incoming president had to confront head-on the Calhoun understanding of the Constitution and the Union.

The Case Against Secession: The Power

of Words

In the four months between his election and inauguration (the political calendar was more leisurely back then), Lincoln quietly rallied his party in a united stand against the secessionist tide. “Stand firm,” he wrote one congressman. Don’t consider “compromise of any sort,” but rather “hold firm, as with a chain of steel.”

Finally it was his turn. Lincoln carefully crafted an inaugural address that began in conciliation, switched subtly to firm warning, and ended in a heartfelt overture of peace.

The speech first spoke directly, and reassuringly, to Southerners. You misunderstand me, he said, if you fear I will interfere with slavery. Even laws implementing return of runaway slaves will be upheld, because the Constitution explicitly provides for such laws.

But then he turned to the issue of the seceding states: “A disruption of the Federal Union heretofore only menaced, is now formidably attempted.” Notice, although the Confederate States of America was functioning, Lincoln acknowledged only that a “disruption” was “attempted.” That is because, he immediately asserted, “I hold that ... the Union of these States is perpetual.”

Even if the Union were, as the Calhounians had it, a contract among independent parties, it could “be peaceably unmade” only by the consent of all the parties to the pact — the other states. But it’s not a contract, for “the history of the Union itself” confirms that “the Union is perpetual.” Indeed, the Union predates the Constitution, and the Declaration of Independence as well. It came into existence in the form of the Continental Congress, while the 13 states were still colonies.

Now the fist. “It follows,” Lincoln coldly proclaimed, that any supposed ordinance of secession is “legally void,” so any acts resisting “the authority of the United States, are insurrectionary.” Thus by Constitutional mandate “the Union is unbroken,” and the president duty bound to ensure that “the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in all the States.” Lincoln would enforce federal authority even in states imagining themselves seceded.

After an extended civics lesson on the practical absurdity of a government that provided for its own dissolution, Lincoln reverted to a stark moral statement, one he had used before: “One section of our country believes slavery is right, and ought to be extended, while the other believes that it is wrong, and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute.”

And then, nearing the end, came the earnest appeal to both the circumstances and the oath, which began this essay: “My dissatisfied fellow countrymen," do not fear any aggressive act. Yet you have no sacred sacred pledge to war against the government, but I have my oath to defend the Constitution.

And finally, the soaring and poignant ending:

We are not enemies but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory ... will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

The Case for the Constitution: The Power of Action

A dispatch the next day exploded the wistful hopes of Lincoln’s closing plea. The officer commanding the federal garrison at Fort Sumter, in Charleston harbor, reported his supplies were running low. If not resupplied, he must surrender. It was the first test of Lincoln’s resolve to execute the laws of the land without provocative actions. After agonizing a month, he determined to send provisions — but not arms — and to notify South Carolina’s governor. Lincoln’s initiative forced the Confederacy’s hand, and South Carolinians (again!) opened fire on the federal fort on April 12. The war was on.

Lincoln took immediate and decisive action. He asked for volunteers to suppress the rebellion. He called Congress, not slated to reconvene until December, into emergency session. He moved quickly to secure those border states that had not yet seceded. He ordered arrests of Southern sympathizers.

His oath compelled his actions. By building the case that secession was constitutionally impossible, he could characterize Confederate resistance, especially after Sumter, as a domestic insurrection, which the Constitution authorized the government to suppress. And though raising an army to do so was the province of Congress, the Constitution designated the president as commander-in-chief of that army, a role Lincoln would exploit to the fullest, managing a vast and brutal war that ultimately crushed the rebellion and preserved both Union and Constitution.

But that’s another story.

The Case for the Nation: The Power of Victory

Abraham Lincoln was cut down by an assassin’s bullet at the moment of triumph — four long years after the guns of Sumter and five short days after General Robert E. Lee surrendered. But the martyred president’s constitutional vision endured. Lincoln’s iron refutation of secession, in legal argument and executive action, combined with the Northern victory on the battlefield, transformed the constitutional order of the American republic. His exercise of power, first in lawyerly words and then in decisive acts, set the North on the path to victory and reunion.

Henceforth, the center of political gravity would shift from state to central government, and from Congress to the presidency.

Lincoln’s generation referred to their country as “the Union” — a mystical aggregation of local parts. Lincoln, we still say, saved “the Union.” But Lincoln also introduced a revised vocabulary, when in his Gettysburg Address he said the founders “brought forth ... a new nation, conceived in liberty.” Ever since, we’ve adopted his alternative word: We speak of our nation — clearly one.

And clearly run from Washington, DC. Yes, we treasure and trumpet our local and particular identities. Yet our multifaceted society has (at least so far) remained intact as constituted. Our nation, under the enduring Constitution of 1787, has been spared another war of brother against brother.

All politics is local, it is said. But all politics is irrevocably national as well, thanks to Abraham Lincoln’s insistence that “the Union of these States is perpetual.”

Professor of History William Woodward joined the Seattle Pacific University faculty in 1974. He specializes in the history of the Pacific Northwest, especially military history; and American culture. The recipient of numerous grants and honors, he also gives public lectures on history and is a consultant.

Professor of History William Woodward joined the Seattle Pacific University faculty in 1974. He specializes in the history of the Pacific Northwest, especially military history; and American culture. The recipient of numerous grants and honors, he also gives public lectures on history and is a consultant.