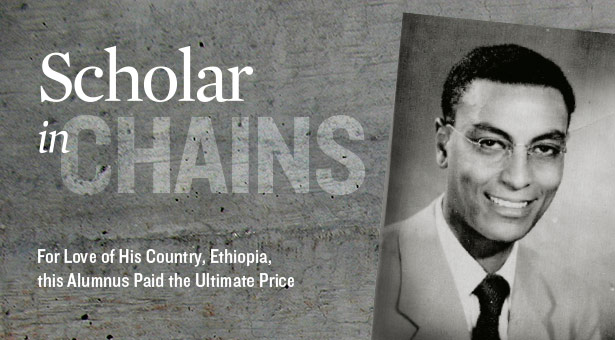

Kassa Wolde-Mariam,

pictured just before he left

Ethiopia to study in the U.S.

Kassa Wolde-Mariam,

pictured just before he left

Ethiopia to study in the U.S.

By Clint Kelly (ckelly@spu.edu) | Photo courtesy of Amaha Kassa

In 1954, Ethiopian student Kassa Wolde-Mariam transferred to Seattle Pacific College. That summer, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie and his entourage paid their first visit to the United States. Included in the royal party was the 19-year-old, British-educated granddaughter of the Emperor and Kassa’s future wife, Princess Seble Desta.

Kassa and Seble had yet to fall in love. Neither knew then that they had a future together, one filled with children, significant achievement, and unspeakable tragedy. In 1954, he was content to plunge headlong into political science, while she enjoyed the international travel made possible by the position and celebrity of her charismatic grandfather.

One day, Kassa, who hailed from a noble family of the Oromo tribe, would be addressed as “His Excellency.” One day, he would become the first president of Ethiopia’s first university and bring much-needed reform and progress to his homeland. One day, he would pay the ultimate price for his proximity to the throne.

A writer, a poet, and a high school soccer player, Kassa, or Casey as he was sometimes called by his SPC classmates, presented a handsome, regal bearing and commanding intellect. In his senior year, his confidence and interest in world politics won him the chairmanship of the SPC delegation to the sixth Model United Nations assembly at Oregon State College, where he distinguished himself among 1,000 students from 87 colleges of the Pacific western states. Kassa, head of the “Romanian delegation,” gained control of the preliminary communist caucus and debated such weighty issues as disarmament, economic reform, and independence for a variety of nations.

Kassa, as a Seattle Pacific

student, frequently appeared

in Falcon student newspaper

articles mentioning his leadership

of the Model U.N. and

International Relations Club.

Kassa, as a Seattle Pacific

student, frequently appeared

in Falcon student newspaper

articles mentioning his leadership

of the Model U.N. and

International Relations Club.

This and his time as president of the SPC International Relations Club provided a foretaste of a life of public service. Among its many hallmarks would be Kassa’s firm defense of freedom of speech, whether he agreed with that speech or not.

“He was very mature and a fine representative of his country,” remembers classmate Jerome Kenagy ’56. “He was biblically literate and personally devoted to his beliefs,” adds Norm Edwards ’56.

In 1972, as Seattle Pacific’s alumni director, Edwards traveled to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and had dinner with Kassa and his family. Says Edwards, “Kassa prayed a blessing on our meal and expressed great appreciation for his years at SPC.” He also emphasized how much those years had influenced his career and his ability to engage society “beyond the traditional walls of the church.”

Unknown to Kassa and his American guest, two years later the tidal wave of socialist revolution would crash over Ethiopia, and Kassa would be thrown into prison.

A Consummate Intellectual

Raised in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and partially educated in Seventh Day Adventist private schools, Kassa first came to North America on a scholarship to Canada’s Prairie Bible Institute, sponsored by Christian missionaries he met in Ethiopia. He later transferred to SPC to broaden his academic studies.

“He was a genuine intellectual,” says Kassa’s only son, 40-year-old Amaha Kassa, a grassroots organizer and nonprofit director in New York City. (In Ethiopian culture, it is customary for children to take their father’s first name as their last name.) “He thrived at Seattle Pacific and was constantly in the student newspaper,” Amaha continues. “The training in debate served him well later in life as president of the state university, especially when he spoke to a more radical student element. Those students said he heard their demands but rather than fight with them, would reason until he had changed their minds.”

Because of the tragic events that overtook Kassa by the time of Amaha’s birth, the son never knew his father personally. To flesh out the details told him by other family members, including four sisters, and for answers about his father’s time in America, Amaha visited Seattle Pacific to search the SPU Archives in the summer of 2013. “The life of the mind was central to who my father was, a man always striving to find common ground with others,” Amaha says. “His interests lay in wrestling with the big ideas of freedom and human meaning.”

Kassa Wolde-Mariam’s future wife, Seble Desta (right)

visited

Seattle with her grandfather,

Emperor Haile Selassie (left)

in 1954 on the

Emperor’s first state visit to

the U.S. Seble received a

bouquet of roses upon the

party’s arrival at SeaTac

Airport. Post-Intellegencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry

Kassa Wolde-Mariam’s future wife, Seble Desta (right)

visited

Seattle with her grandfather,

Emperor Haile Selassie (left)

in 1954 on the

Emperor’s first state visit to

the U.S. Seble received a

bouquet of roses upon the

party’s arrival at SeaTac

Airport. Post-Intellegencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry

Kassa’s genius soon captured the attention of Ethiopia’s eloquent monarch, heir to a dynasty that traced its origin by tradition from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

“In my father’s day, the Emperor took a personal interest in the relatively small number of Ethiopian students who studied abroad,” explains Amaha. “He was trying to bring his country into the 20th century and saw education as critical to that.” Soon Selassie also considered Kassa an ideal match for his daughter, Princess Seble.

“More than that,” says Amaha with a chuckle, “my mom and dad were crazy about each other. I mean, they went on to have five kids. Believe me, there were other candidates in the wings, but my mother had her own ideas about the match!”

Seble, who also now goes by the anglicized “Sybil,” was taken with the tall, good-looking man she remembers for his energy, ready laughter, and ability to listen. “He was interested in the lives of other people,” she says. “He was very sure of himself, but not pushy. His was a special sense of humor expressed even in the dark, difficult times.”

Kassa and Seble had much in common; both were well-traveled and they shared similar tastes. Though their families knew each other, Seble says they became romantically interested in one another while working together in the Selassie government, she as a secretary and he as an assistant to the Emperor.

Later, when children came and travel on state business increased, Kassa spent as much time as possible taking his daughters Jote, Yeshi, Laly, and Kokeb camping and to places of interest and historical significance. “He gave them much joy,” remembers the princess.

Two years later the tidal wave of socialist revolution would crash over Ethiopia, and Kassa would be thrown into prison.

One of her fondest memories was of a family drive in the countryside when Kassa was governor of Welega Province. The day was cold and rainy and the roads outside the capital not well maintained. Their Jeep became stuck in the mud and the family had to be rescued by people on foot from a nearby town. They freed the vehicle, but now there were too many people to fit in the Jeep and the rain continued to fall.

More than 40 years later, Seble recalls the impact their father’s example left on the children. “Kassa insisted that everyone else ride first, that the governor would come along later.” He looked, she says, for people in need of help, and insisted on kindness and honor before rank.

1954

Kassa Wolde-Mariam transfers to Seattle Pacific College.

1954

June 11 Emperor Haile Selassie (right) visits Seattle, Washington, as part of his first state visit to the U.S. The party includes his granddaughter Princess Seble Desta (left).

1956

April Kassa represents SPC at Model United Nations.

1956

June 11 Kassa graduates from SPC with political science degree.

1958

Kassa receives master’s degree from University of Washington.

1959

January 31 Kassa marries Seble Desta in Addis Ababa.

1960

Kassa appointed assistant minister in the Ministry of the Pen and private secretary to His Imperial Majesty; an upstart coup d’etat is crushed by the Emperor.

1962

Haile Selassie I University is formed, and Kassa Wolde-Mariam is appointed the university’s first president. His tenure ends in 1969.

1965

May SPC President C. Dorr Demaray visits Kassa in Ethiopia during his tenure as president of HSIU. Demaray highlights Kassa’s “personal commitment” and “aggressive professional achievement” in a speech at Ivy Cutting ceremony.

1965

August 12 Kassa delivers SPC’s first summer Commencement address.

1969

Kassa appointed governor of Welega province.

1972

Norm Edwards ’56 travels to Addis Ababa to visit Kassa and his family.

1974

January 12 Revolution begins as army officials mutiny against commanding officers.

1974

January Kassa arrested and imprisoned in Menelik Palace.

1974

June The Derg, a military junta, is officially established with Mengistu at its head, and roundups of intellectuals and counter-revolutionaries begin.

1974

September 12 Haile Selassie is formally deposed by the Derg and imprisoned.

1974

September Seble Desta is imprisoned with eight other imperial princesses.

1975

August 27 State media announces Haile Selassie’s death due to “failing health.”

1975

September Mengistu institutes “Red Terror,” a brutal campaign targeting perceived opponents and leaving dead bodies piled in the streets. At least 10,000 people are killed before the campaign ends in 1978.

1979

July 14 Kassa Wolde-Mariam is executed.

1987

The Derg is formally dissolved 1988 and Mengistu establishes the People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

1988

September Seble Desta released from prison.

1991

Rebel forces take control of northern Ethiopia, forcing Mengistu to flee and the regime to collapse.

1995

Ethiopia holds first multiparty elections.

Becoming a University President

This is the historic gate of Addis Ababa University, formerly Haile Selassie University, which Kassa Wolde-Mariam served as

president.

This is the historic gate of Addis Ababa University, formerly Haile Selassie University, which Kassa Wolde-Mariam served as

president.

Just two years after receiving his diploma from SPC President C. Hoyt Watson, Kassa returned to Ethiopia and was quickly appointed to the Ministry of the Pen and private secretary to the Emperor. A trusted confidante, he assisted in the writing of Selassie’s speeches, helped formulate statements of government policy, and crafted official correspondence with other heads of state.

In 1962, Kassa was named founding president of the newly renamed Haile Selassie I University (formerly and presently Addis Ababa University). His appointment to the state university coincided with a new chapter in Ethiopia’s prospects. Loans from the United States, Russia, and the World Bank were secured to improve highways and communications, fund mechanized agriculture, and develop industry. The 2,500 full-time students and 3,000 part-time and extension students under Kassa’s oversight were the country’s brightest hope for nation building.

During Kassa’s seven-year tenure as president, the university experienced extensive development. He established schools of education, medicine, and law. Almost anyone who went to college in Ethiopia knew him. His presidency, 1962–69, embraced the age of dissent, not only in America, but in other parts of the world. The campus saw its share of unrest, which Kassa addressed with a steady hand.

Facing Turbulent Times

Soldiers march in a parade commemorating the fourth anniversary of the Ethiopian Revolution in which the Derg deposed the late Emperor Haile Selassie, in Addis

Ababa, Ethiopia, September 1978.

Soldiers march in a parade commemorating the fourth anniversary of the Ethiopian Revolution in which the Derg deposed the late Emperor Haile Selassie, in Addis

Ababa, Ethiopia, September 1978.

Meanwhile, opposition to the Selassie regime mushroomed. For some, the pace of reform was too slow — the standard of living in the provinces remained low while illiteracy remained high. Marxist factions gained ground and rivers of dissatisfaction against the aristocracy neared flood stage.

Kassa remained optimistically resolute in the face of political storms. American-educated and a dynamic leader, the president enjoyed high popularity among university faculty, staff, and students. It was said that his prior government service was known for its loyalty, discretion, dignity, and efficiency.

“All my life I have heard stories of my father’s lifelong commitment to public service,” says Amaha. “Though he later became the minister of agriculture and governor of Welega Province, his biggest legacy remains the university. Even those who differed politically speak glowingly of his integrity and courage.”

Kassa returned to America in 1965 to recruit faculty members, and to his alma mater to deliver the keynote address for SPC’s first summer Commencement. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer quoted parts of the speech that punctuated what he dreamed for Ethiopia, but in light of subsequent events, are words that now haunt. He described Ethiopia as “a stable nation, not given to tempestuous changes,” that was working in many fields to improve itself. One year later, anti-intellectual revolutionary forces would begin to dismantle the monarchy and eventually resort to slaughter to “cleanse” the country of the old regime.

In November 1973, a son was born to Kassa and Seble. They named him Amaha, “gift from God.” But with joyous birth came ever more somber news. The revolutionary river had burst its banks and anti-imperial forces roamed the land. What Amaha now calls “the unraveling” had begun.

For their safety, the three youngest children, including baby Amaha, were sent to Britain and eventually to the U.S. under the auspices of western missionaries in Ethiopia. Their two older siblings were already at boarding school in England.

Members of the imperial line were soon found murdered or dead under mysterious circumstances. In January 1974, Kassa, now the minister of agriculture brought in to address repeated famine, was arrested and disappeared into the dank recesses of Menelik Prison, formerly the palace of Emperor Menelik II.

Seble fared no better. She was one of nine princesses thrown into prison under harsh conditions, her head shaved, kept without charge. She and her sisters lived in dungeonlike conditions in a damp 10-by-12 foot concrete cell with two mattresses between them. Visitors were not permitted, and a radio provided their only tie to the outside world. Seble lived for 13 years cut off from those she held dearest, including her infant son. The next time Amaha saw his mother and finally learned that she had survived, he was in high school and nearing his 14th birthday.

“There’s nothing I can do to bring my father back. I can’t change the past, but I can help others change their future.”

“Sadly, they were quite young when we were imprisoned — our only son was not yet 1 year old — and their father’s passing was horrendous,” Seble says. Today she lives in a Virginia suburb of Washington, D.C. She does not like to talk about those most painful times.

The year Ethiopians felt the wrath of the socialists under military dictator Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam’s brutal command, famine intensified. It began in Wollo province, still impoverished by the famine of 1966, and spread throughout the adjoining northern provinces. The weakened imperial government crumbled under its failure to adequately handle the crisis. A committee of low-ranking military officers called the Derg took control of the country, led by the brutal Mengistu.

On November 23, 1974, “Bloody Saturday,” 60 officials and former officials of the Selassie government were executed and buried in a mass grave in Central Prison near Haile Selassie I University (within months stripped of the name). Eight months later, the regime announced the Emperor’s death of “natural” causes — though later evidence suggests he was assassinated. He had ruled his people for 44 years.

The Derg turned the Grand Palace of Emperor Menelik II into its official seat of government — with a dank holding cell for Kassa and others whose final fate was yet undetermined. Kassa lived five more years a prisoner, his only crime being the son of a nobleman and the husband of a royal. Leaders and intellectuals were suspect for supporting what some factions considered despotic rule.

“He was held, never charged, promised a trial that never came, and clandestinely killed,” says Amaha.

Faithful Behind Bars

Amaha Kassa holds a photo of his father, Kassa Wolde-Mariam, outside his New York home. Photo by Brooke Fitts

Amaha Kassa holds a photo of his father, Kassa Wolde-Mariam, outside his New York home. Photo by Brooke Fitts

In prison, Kassa kept busy in confinement and continued under primitive conditions the scholarship that so defined his better days. One of his projects was the writing of a dictionary. “He was of the Oromo people and my mother was Amhara,” says Amaha. “Using hundreds of tiny scraps of paper maybe twice the size of Post-it Notes, he constructed an Amharic to Oromo dictionary that he rolled up into a scroll filled with his impeccable handwriting.”

The other project that consumed the long hours in confinement was penning a partial concordance to the Bible in Amharic. It included all biblical references to Ethiopia and its people.

Saturday, July 14, 1979, was the feast day of the Holy Trinity. Reports say that His Excellency Lidj Kassa Wolde-Mariam (“Lidj” is the Ethiopian equivalent of a British “lord”) was led from his cell and went to his knees before fellow prisoner and priest, Patriarch Abune Tewophilos, who gave him absolution. Kassa rose and followed his executioners to the appointed spot where Amaha believes his father was strangled to death. Some reports say that his confessor died with him in the same manner.

The Derg lost power as communist regimes around the world crumbled with the fall of the Iron Curtain. Though now a democracy, Ethiopia wrestles with its legacy of violence from just decades ago, and human rights abuses are still reported.

“The ’60s and ’70s were an extremely turbulent time for Ethiopians — think of Syria today,” says Don Holsinger, SPU professor of history, “with provincial and neighboring rebellions, terrible droughts, rapid population growth, rising expectations among the young, and Cold War meddling, to name a few. It’s tempting for Americans to throw a ‘socialist’ or ‘communist’ label on the tragic events following the military coup of 1974, but it is much more complex than that.”

For Amaha, very much like his father, bitterness is a wasted emotion. “My family lost a great deal,” he says. “Most of our male relatives were killed, and much of our status was lost and our finances ruined. There’s nothing I can do to bring my father back. I can’t change the past, but I can help others change their future.” Amaha is the founder and director of ACT, African Communities Together, a national network that seeks to improve the lives of African immigrants in the U.S.

Kassa’s legacy lives on in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa University is in the process of building a new wing named in his honor. The institution’s original founding motto, based on the words of St. Paul in 1 Thessalonians 5:21, perhaps best captures Kassa’s love and hope for the people of Ethiopia: “Deliberate freely on all matters and hold on to the best.”

It is also a fitting eulogy for one Seattle Pacific alumnus bright with promise.

In life, Kassa Wolde-Mariam labored for his nation’s renewal; in death, his selfless example of servant-leadership remains a beacon to all who come after him.

SPU senior Kelsey Chase also contributed research to this story.