Features

Coffee Meets Chemistry

His dad's legacy inspires this Seattle Pacific University

student to brew coffee success at Starbucks

By Jeffrey Overstreet | Photos by David Cho

Falling down is hard. Ask any snowboarder or surfer. Ask anybody who commutes by moped. Ask laboratory scientists.

Ask Seattle Pacific University senior Bo Valencia — who happens to be all of the above. He has learned, from his remarkable family history, that stumbles can be the steps that lead to success.

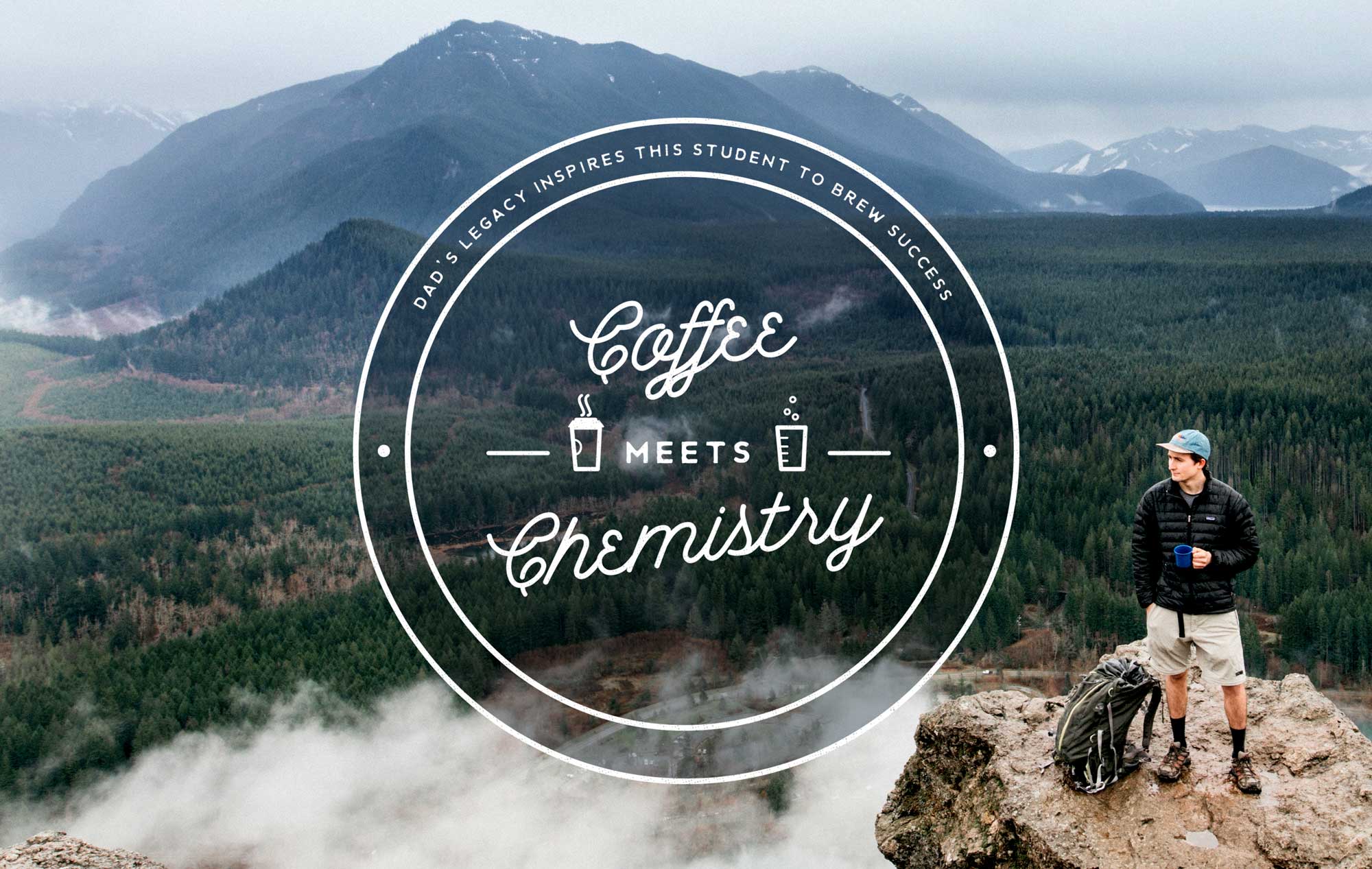

Brewing a package of

Starbucks VIA coffee on an

outdoor stove comes naturally

to Bo Valencia. He has worked

as a mountain-climbing guide

for Seattle's Union Gospel

Mission.

Brewing a package of

Starbucks VIA coffee on an

outdoor stove comes naturally

to Bo Valencia. He has worked

as a mountain-climbing guide

for Seattle's Union Gospel

Mission.

It’s best to begin Bo’s story in 1988, five years before he was born, when his father, Don Valencia, was a cell biologist and co-founder of his own company. To simplify the way they transported cells — cells were typically shipped in dry ice — he began freeze-drying cells and then re-hydrating them with a special solution when they completed their journey.

Don’s freeze-drying innovation didn’t stop there. An avid outdoorsman, he disliked his campfire coffee options. So he created a fine-ground coffee concentrate at home and took it to work for experimental freeze-drying. As he refined his art, he would set two wine glasses — one with fresh-brewed coffee and one with instant — on the fence for the neighbors to try. Eventually, they couldn’t tell the difference. He started selling his concoction in a boutique café.

During a visit to Seattle’s own Pike Place Market Starbucks, he offered baristas a taste. “Yeah, right,” they said. “We’re not going to try that.” Then, Bo says, as Don walked to his car, he was chased down by some Starbucks’ employees. Their curiosity had gotten the better of them. A week later, Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz flew to the Valencia home to learn more about Don’s work, and a period of brainstorming began. In 1993, soon after Bo was born, Starbucks hired Don as their first head of research and development.

Don’s big break led to failures as well as phenomenal success. The most significant flop? Mazagran: a carbonated coffee beverage that polarized customers and went off the market quickly. Out of that “failure” came an extract for the Frappuccino formula. And Frappuccino earns Starbucks around $2 billion annually, essential to the company’s success with ice cream, liqueurs, and more.

“My dad taught us that we arrive at success by taking all those steps of failure to get there,” says Bo. That’s why my mother’s license plate says ‘MAZGRAN.’ And it’s why Mazagran is the name of my brother’s photography company.”

In 1999, Don retired to do nonprofit work. As co-chair of the board for Agros International (founded by Chi-Dooh “Skip” Li ’66), he supported poor, rural families in Central America and Mexico. His wife, Heather, says that while Don’s life was “centered on Jesus,” his faith, like his ideas, was more a matter of “living it out rather than talking it out.”

SPU senior Bo Valencia is an avid

outdoor sports enthusiast who has led four summer

expeditions on Mt. Rainier.

In 2006, as Starbucks revisited Don’s instant-coffee innovations (the project’s code name was “Stardust”), Don began treatment for cancer. He passed away 15 months later. But just before he did, Schultz told him that Starbucks had finally fulfilled his dream: “Stardust” would soon be sold in stores. When Starbucks unveiled their invention, they called it “VIA.” The word had an “on-the-go” quality to it — but Schultz also saw it as an abbreviation of “Valencia”: a tribute to Don’s innovations.

“My dad liked to do things and not get credit for it,” says Bo. “But he wasn’t really in charge at that point, so he got the credit anyway.”

Heather sees Don’s strengths — his action-focused faith, his drive for innovation, his response to stumbles — alive within her son Bo as well. Just as Don turned the kitchen into a lab, Bo was a young “kitchen chemist.” Just as Don “gave back,” so Bo has taken opportunities to volunteer.

Bo describes hard times at school as his “own personal Mazagran.” He took Calculus II three times, persevering until he passed. “Because of what my father taught me, I was able to stick with it and keep trying my best.” His dyslexia seemed, at times, insurmountable — but it led Bo to SPU’s Center for Learning: “They’ve been a huge help for me,” he says.

Bo kept learning from his father through a Starbucks R&D internship, which became a job. His mentors at Starbucks pass on life lessons they learned from his father, who hired them. Learning on the job, he decided to change his major from biology to biochemistry so that he can work, like his dad, on soluble coffees.

“I feel sort of like Harry Potter going into the world of magic,” he says. “It’s great to use the same instruments I’ve used in SPU labs. Our instruments make me think about pressure, temperature, and different compounds for water, and about how those things affect the water, the pH, and the different molecules in coffee. All of it influences the coffee’s aroma, its body, and its mouth feel.”

In 2014, Eric Long, associate professor of biology at SPU, took Bo and 13 other students to Ecuador, where they celebrated Christmas with a missionary family, and then moved on to the Galapagos Islands to study marine and terrestrial ecosystems, and the environmental issues that threaten the islands.

“Bo does bench science in the lab, works with hard-core technology, and then goes mountain-climbing, snowboarding, and surfing. He takes full advantage of our Pacific Northwest surroundings,” Long says. And Bo was impressed to learn how his Christian professors integrated evolution with their Christian faith.

Bo’s love for hands-on learning reflects his father’s Renaissance-man reputation. “My dad would work on something, master it, then work on something else and master that.” Bo is considering an executive master’s degree in business technology, and he keeps a PowerPoint file full of invention blueprints. But Starbucks is central to his plans. He loves the feeling of walking through a warehouse-sized version of his dad’s kitchen counter operation, one that produces enough VIA to serve millions of people.

When he took time off from Starbucks to focus on his studies this year, he had vivid dreams about being back at work. “Those dreams made me so happy,” he says. “Then I’d wake up and think ‘Oh, no!’” Someday he’d like to follow his father in another way: as a mentor for Starbucks interns.

But for now, there’s more coffee to invent. “My main project over the summer will be in stores next Christmas.” He smiles secretively. “I can’t share what it is.”