Features

The Man and the Machine - La Marzocco

For Decades, La Marzocco CEO Kent Bakke Has Played a Role

in the Evolution of Seattle Coffee Culture

By Hannah Notess | Photos courtesy of La Marzocco

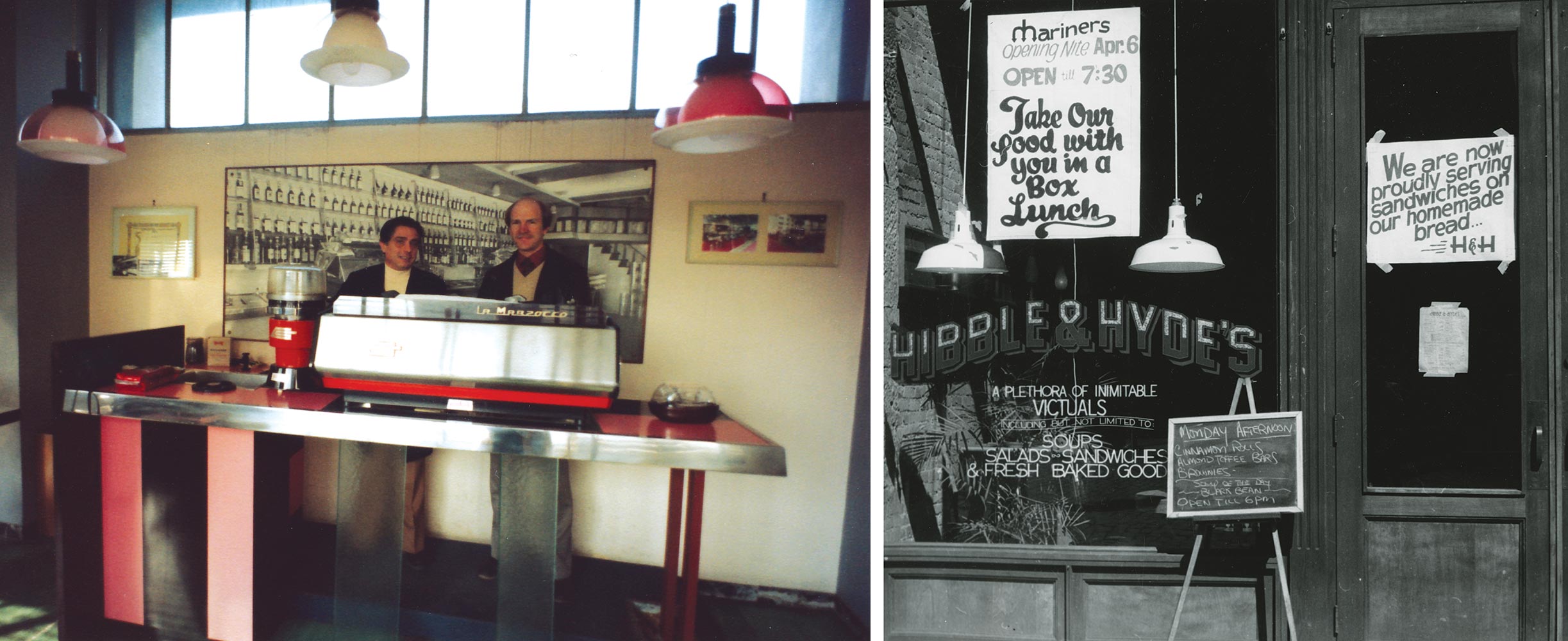

A large, brass machine sat on the back counter in Hibble & Hyde’s café, a tall, barrel-chested gadget that was supposed to make coffee. But it wasn’t working, and Kent Bakke ’74 needed to to fix it.

A recent graduate of Seattle Pacific University, he was now a co-owner of the café in Seattle’s Pioneer Square. He and a few friends had bought the defunct sandwich shop and were trying to turn it around. That included the machine nobody knew how to use.

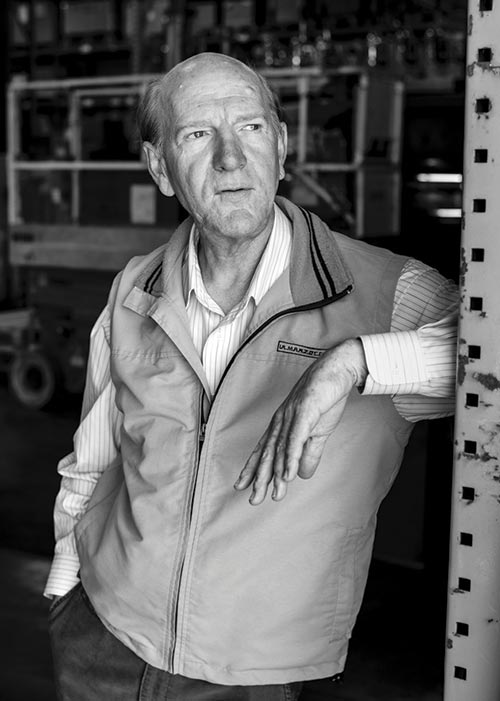

Kent Bakke has helped to make global coffee history with La Marzocco.

Kent Bakke has helped to make global coffee history with La Marzocco.

Espresso was already on the restaurant menu, for 25 cents.

“I was not actually a coffee drinker at the time,” Bakke says. Nor did he know he was poised to become a part of global coffee history.

Bakke enjoyed fixing things and working with machines — he had grown up working summers for his dad’s truck body company in California’s San Joaquin Valley. He and his friends started working on the old espresso machine, to see if they could get it to work. At first, the results were less than ideal.

“It tasted terrible,” he recalls.

But they kept tinkering, and kept tinkering, and eventually figured out how to get it working. Then they got to know the other six or seven businesses with espresso machines in Seattle, and started to repair those machines. One of Bakke’s fellow tinkerers was John Blackwell ’70. The two had met while students at Seattle Pacific. “Kent’s car wasn’t working and he asked if I could start it,” Blackwell says. “I like to say I’ve been fixing Kent’s stuff ever since.”

Although they hadn’t exactly perfected the espresso flavor, Bakke and his friends saw an opportunity early on. There were plenty of hippies, he says, who had developed a taste for Italian-style coffee while traveling around Europe.

So Bakke and some friends traveled to Italy to see if there was a possibility of importing espresso machines. Bakke fell in love with the culture around food, around everything being made from scratch.

“Everything tasted different when I got to Italy,” he says. “I just walked around with my jaw open.”

Above, left: Piero Bambi and Bakke pose in the early days with a classic Bambi-designed

machine. Above, right: A photo of Hibble & Hyde's cafe from the 70s, in Seattle's Pioneer Square, where Bakke worked on his first espresso machine.

They visited the La Marzocco factory in Florence, a family-owned business responsible for major espresso innovations. For instance, the founding Bambi brothers, were the first to turn the machine from a vertical boiler, like the one in Hibble & Hyde, to the horizontal shape of modern espresso machines. They were known for top-quality craftsmanship. The Seattlites asked if they could begin importing the machines into the Northwest U.S.

The Bambi family said yes.

So Bakke and his friends brought the machine back and, well, business didn’t exactly take off. It took over a year to sell the first machine.

“We called them cappuccino machines because nobody knew what they were.”

Finally, they put together an espresso cart for the Edmonds Arts Festival in 1979 and started selling the coffee drinks. It was a hit.

Even now, mobile carts or trucks can be a good way for a restaurateur to get start selling food before shelling out for actual brick-and-mortar floor space. Over time, espresso cart culture took off in a big way, and blossomed into a network of carts and stands across the Northwest. In fact, one of the originals, Seattle’s Monorail Espresso, is still home to a La Marzocco machine.

Piero Bambi, of La Marzocco in

Italy, works closely with the

Seattle team.

Piero Bambi, of La Marzocco in

Italy, works closely with the

Seattle team.

“It was starting from scratch,” Bakke says. “We were selling the beverage, the idea of it as much as the machine.” Nobody knew how to use the machines, so they had to do barista training as well as setup and maintenance. But espresso took off in the Northwest, where they sold in five states, including into the remote areas of Alaska. “A town that wouldn’t even have a gas station would want an espresso machine,” Bakke recalls.

Bakke’s connection to La Marzocco has been through several evolutions since those initial coffee carts. For one, Bakke and partners purchased a 90 percent stake in the Italian company in 1994, moving him from importer to an owner. Bakke is CEO; Blackwell is head of product management, and Joe Monaghan, another veteran from the espresso cart days, is company president. To this day, the factory is in Italy, near Florence, and they to work closely with Piero Bambi, nephew of the company’s founding brothers.

And then there was the Starbucks era. When Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz made a move to refocus that business from roasting to cafés, La Marzocco machines were the ones his baristas wanted. They were reliable, well-crafted, and produced great results. Beginning in 1994, La Marzocco manufactured machines for Starbucks in a Seattle factory run by Blackwell. Steam from those machines filled café after café, fueling those decades of Starbucks expansion. That ended in 2004 when Starbucks converted its cafes to superautomatic machines. Of course, there are tradeoffs between the different kinds of machines. With a superautomatic machine, there’s less opportunity for error. Push a button; you know what you’re getting. But a La Marzocco semiautomatic machine gives a skilled barista more control.

“It’s the difference between flying in an airplane and being a pilot,” Bakke says.

La Marzocco remains a major player in the specialty coffee market. Last year, they sold 12,000 machines in 80 countries. The machines are so popular with baristas that some have even gotten tattoos of the La Marzocco logo. And in the company’s Seattle lab, on any given day, espresso-machine service technicians who have traveled from all over the country can be found practicing repairs on the latest Linea PB or Strada machine.

La Marzocco's high quality

craftsmanship makes the

machines popular with baristas.

La Marzocco’s latest evolution involves a café, though it’s a very different one from the sandwich joint where Bakke encountered his first espresso machine so many years ago.

At the newly opened La Marzocco café and showroom at Seattle Center, part of the new home of independent radio station KEXP, the latest machines are on display. The unique space features a rotating cast of quality roasters and thousands of dollars’ worth of beautiful espresso technology. But anyone can also stop in for a cup and some conversation, just like a traditional café.

The place seems poised to become a destination for coffee aficionados. And Bakke is proud of what the new café represents.

“It’s all about building community and coffee passion,” he says.

And though it’s a space dedicated to music, the sound they’re adding is the hiss of steam. That’s the trademark sound of the machines that have defined Bakke’s career, and quietly powered the Seattle — and global — coffee revolution.