Let Justice Roll Down Some More

Thirty-two Years After It Was First Published,

John Perkins’ Autobiography Still Cries Out for Justice and Dispenses Grace

“Let justice roll down like waters, And righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.”

— Amos 5:23

By Margaret D. Smith and Jennifer Johnson Gilnett

For 12-year-old John Perkins, born to rural Mississippi sharecroppers in 1930, his first paying job was also his first lesson in economics. Hired to haul hay, Perkins expected to receive a fair wage — a dollar or two — for a day’s labor. But when he finished work, the white plantation owner handed him only 15 cents. Perkins was angry, but knew that if he refused the coins, he would be seen as a troublemaker and branded a “smart nigger,” something that would make his life “unbearable.”

Nineteen-year-old Perkins served in the Korean War from 1950 to 1953. |

He left the job thinking about how he’d been exploited. “I told myself, … ‘if you’re going to make it in this society, you’ve got to somehow or other get your hands on the means of production,’” Perkins wrote in his autobiography Let Justice Roll Down. “‘Once you get the means of production, you can do good or evil with it. And this man done evil with it.’”

The grade-school dropout with a head for economics and a heart for justice — child of America’s apartheid South — would go on to become one of the world’s most influential evangelical voices for civil rights, economic empowerment of the poor, and racial recon-

ciliation. Thousands of people have come to know his story by reading Let Justice Roll

Down (Regal Press, first printing 1976), in which he described with gripping clarity the events of his life and one of America’s most turbulent periods in history.

After his encounter with the plantation boss, Perkins pondered how to make changes that would improve his own economic circumstances. Eventually, he fled the South, worked his way up into a good-paying job, and, by the 1950s, he and his wife, Vera Mae, owned a 12-room house in Southern California.

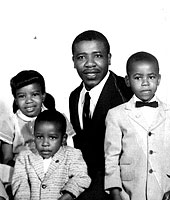

Perkins and his wife, Vera Mae, began raising a family in California in the 1950s. Here he's shown with his three oldest children. |

When he became a Christian in 1957, however, Perkins’

priorities changed forever. He believed God was calling him to

leave his comfortable life and return to his home state. John, Vera Mae, and their five children drove cross-country, back into poverty-ridden and racially charged Mississippi, “to identify with my people there, and to help them break the cycle of despair — not by encouraging them to leave, but by showing them new life right where they were.”

In Mendenhall, Perkins began teaching the Bible, creating self-help cooperatives to foster economic independence, and, before long, raising his voice in civil rights demonstrations.

The progress of the African-American community in Mendenhall — and the leadership of Perkins — was a direct challenge to the traditional white power structure in Mississippi. One evening in 1970, long-pent-up anger and frustration erupted, and Perkins was almost killed at the hands of white Mississippi police officers.

Arrested and imprisoned on an unidentified charge, he was beaten savagely. With an open head wound, barely alive, he was forced to mop up his own blood.

Instead of dying that night in jail, as many thought he would, Perkins survived to spend many months fighting injustice in the court system, fighting depression and a host of physical ailments that came from the beatings, and finally fighting bitterness against whites — including white Christians — who made life so miserable for his people. “Everything added up to the conviction that there was no justice at all,” he wrote in Let Justice Roll Down. “No justice at all for any black who wanted to stand up like a man in Mississippi.”

But during a time of introspection so intense that it was “crucial to the whole meaning of my life,” the 41-year-old emerged with a renewed spirit and vision for the future: “The Spirit of

God kept working on me and in me until I could say with Jesus,

‘I forgive them too.’ I promised Him that I would ‘return good for evil,’ not evil for evil. And He gave me the love I knew I would need to fulfill His command to me of ‘love your enemy.’”

Perkins meditates on a passage of Scripture before preaching a sermon in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1975. |

A Book to Remember

As a first-person narrative of American history, Let Justice Roll Down is a classic. It should be reread with each passing decade so that we remember — remember the era of apartheid and the Civil Rights Movement without newsreel nostalgia, remember the past and present realities of prejudice and racism, and remember the only true antidote to racism.

Remembering the Civil Rights Era requires many of us to confront difficult truths about ourselves. There were white Americans in the South and from the North who marched with their black neighbors and sat side-by-side at drugstore counters, demanding equal rights for all races. As Perkins recounts, some white volunteers worked with his Voice of Calvary ministry, and one young white volunteer was even beaten with him in the Brandon jail. But many more whites stood silently by while others tortured and even killed the African Americans brave enough to stand up to the stomach-turning injustice they faced.

Racism, wrote Perkins, affects everyone. “A lot of our people were sick — affected by generations of slavery, oppression and exploitation — psychologically destroyed. But I had never thought much before about how all that had affected whites — how they had been affected by racism, by attitudes of racial superiority, by unjust lifestyles and behavior.” White people, he concludes, had been made sick by racism, too.

The newest edition of Let Justice Roll Down (Regal, 2006) includes a preface in which Perkins calls upon people to remember.

He writes about the racism and racial wounds that exist three decades after he first penned the book. Without deep soul-searching and repentance, the wounds will not heal, and the potential for further repression will persist, he argues. To forget the brutality and injustice of America’s apartheid past is “self-deception.”

“I know,” writes Perkins, “because for repentance and forgiveness to work in my life, God had to see me through months of agony and pain … .”

For the man who has sought to live out “the whole gospel” — one that addresses the full range of people’s needs, including spiritual, social, political, and economic needs — the most heartbreaking reality he experienced was the realization that the evangelical church wouldn’t be at the forefront of the march for civil rights; in fact, it wouldn’t be present at all.

“The most terrible thing about the situation in the South,”

he wrote in Let Justice Roll Down, “was that so many of the folks who were either violently racist or who participated in discrimination … called themselves Christians. The question on my mind … was whether or not Christianity was a stronger force than racism.”

Let Justice Roll Down

by Dr. John Perkins

|

Ultimately, the radical message of Let Justice Roll Down is that the love of Christ is a force stronger than racism. As Perkins laid on his sickbed, contemplating whether to “work only for me and mine,” an image of Christ on the cross filled his mind: “This Jesus knew what I had suffered. … Because He had experienced it all Himself. … But when He looked at that mob that had lynched Him, He didn’t hate them. He loved them. He forgave them. …

“It’s a profound, mysterious truth — Jesus’ concept of love overpowering hate. I may not see its victory in my lifetime. But I know it’s true. I know it’s true, because it happened to me. On that bed, full of bruises and stitches — God made it true in me. He washed my hatred away and replaced it with a love for the white man in rural Mississippi.”

In the book’s foreword, author Shane Claiborne writes,

“John cries out with the prophets, ‘Let justice roll down,’ yet he will surprise you with his grace.” Justice and grace — read

Let Justice Roll Down and learn again the glory of both.

Margaret D. Smith ’80 is a freelance writer, and founder and CEO of Clean Green Studios LLC, where she works to shelter the homeless by designing sustainable dwellings for people in developing nations.

Return to top

Back to Features Home

|