Selections From the Prophets Week 13

A Call to Holiness: Zephaniah 3:11–20

Professor of Christian Ministry, Theology, and Culture

Read this week’s Scripture: Zephaniah 3:11–20

11:54

Enlarge

Enlarge

Dies Iræ: The Day of Wrath

In the Vulgate (the late fourth- and early fifth-century translation of the Bible by St. Jerome), Zephaniah 1:15–16 is translated as follows:

Dies iræ, dies illa, dies tribulationis et angustiæ, dies calamitatis et miseriæ, dies tenebrarum et caliginis, dies nebulæ et turbinis, dies tubæ et clangoris super civitates munitas et super angulos excelsos.

(“That day is a day of wrath, a day of tribulation and distress, a day of calamity and misery, a day of darkness and obscurity, a day of clouds and whirlwinds, a day of the trumpet and alarm against the fenced cities, and against the high bulwarks.” (Douay-Rheims translation)) [author’s Note 1]

This notion of the “dies iræ,” or “day of wrath,” has framed the writing of requiem masses by Mozart, Verdi, Stravinsky, and Berlioz; has been the foundation for Gregorian chant and four-line medieval neumatic plainchant; and has served as the theme for the Catholic liturgy for centuries. This day of wrath has become a cultural mood in mass culture as well, evoking from the end-times fervor of alien-invasion films to apocalyptic novels such as the Left Behind series. Needless to say, our culture has long been concerned with the end times, and the horror of God’s finally coming in vengeance is not just the stuff of the Cineplex or Mozart’s Requiem. As we shall see in our reflections drawn from the prophet Zephaniah, the day of wrath is a very real thing. Yet it is only part of the story.

Weaving Prophetic Literature Into a Tight Synthesis

Zephaniah in many respects offers a synthesis of the prophetic voices we have encountered throughout our journey thus far in the prophetic literature of the Old Testament. While amounting to only three chapters, Zephaniah reminds us in no uncertain terms of the key themes that underscore the prophetic literature and passion with which the prophets call the people to a right relationship with their God. As Rex Mason states in the Oxford Bible Commentary entry on Zephaniah,

There is a dearth of unambiguous references to historical events and, as we shall see, there appears to a be a tendency towards a more generalizing interpretation of earlier prophetic material, which may suggest a complex redactional process as earlier oracles were edited, exegeted, and found to be relevant in new situations. [Author’s Note 2]

Two things we are to hear in this: that in order to understand Zephaniah fully we must reflect back on some of the themes already addressed in previous Lectios, and that, as William Shakespeare put so eloquently, the “past is prologue” [Author’s Note 3], in that what has come before will always help us understand our present and our future. What is clear through the canonization of Zephaniah is that, although this book offers in many ways a repetition of themes already encountered, by returning to them we are to reread them in light of today and tomorrow. David Peterson lists the summary nature of Zephaniah in this way:

In sum, the book of Zephaniah deploys many Israelite images and traditions in formulating its speeches. Day of the Lord, creation, Zion, and covenant traditions are only the most prominent of such rhetoric. [Author’s Note 4]

In the first week of this series of Lectios, I suggested some dominant themes found in three Hebrew terms that pervade and ground all the prophetic literature — the call to justice (mišpāṭ); the call to a righteousness (ṣedāqâ) that will challenge the status quo and require an uprooting and literal pruning back of the dominant power structure of the day; and a plea to turn (hāpak) away from sin and face God anew. These three — justice (mišpāṭ), righteousness (ṣedāqâ), and a plea to turn (hāpak) away from sin — are all found in Zephaniah as well.

“On That Day” — A Descendent of Kings Who Challenges the Kings

As the first verse tells us, Zephaniah is the “son of Cushi son of Gedaliah son of Amariah son of Hezekiah, in the days of King Josiah son of Amon of Judah.” (1:1) Scholars have generally accepted this designation, which places Zephaniah as the great-great grandson of Hezekiah, king of Judah from 715 through 697 B.C., and also a distant relative of King Josiah, who reigned from 640 to 609 B.C. [Author’s Note 5]

Other than this lineage, there is little else we know about the prophet. Given the dates found in this lineage, Zephaniah is associated closely with the prophesies of Nahum and Habakkuk at the end of the seventh century, yet this royal lineage puts Zephaniah in a particular position with which to challenge the systems of power that have silenced the ways of God. He begins his indictment of the royal households in 1:8–9:

And on the day of the Lord’s sacrifice I will punish the officials and the king’s sons and all who dress themselves in foreign attire. On that day I will punish all who leap over the threshold, who fill their master’s house with violence and fraud.

The refrain “on that day” brings us back to our previous reflections (see Week 4 and Week 12) on the use of yôm for “day” as not denoting merely a 24-hour period. Here the refrain “on that day [yôm]” is repeated over and over throughout the first chapter, akin to the sound of waves crashing against the shore, with each successive wave pulling back another stain to leave the earth pure once again. This is particularly evident in 1:14–16:

The great day [yôm] of the Lord is near,

Near and hastening fast;

The sound of the day [yôm] of the Lord is bitter,

The warrior cries aloud there.

That day [yôm] will be a day [yôm] of wrath,

A day [yôm] of distress and anguish,

A day [yôm] of ruin and devastation,

A day [yôm] of darkness and gloom,

A day [yôm] of clouds and thick darkness,

A day [yôm] of trumpet blast and battle cry

Against the fortified cities

And against the lofty battlements.

What is clear is that the “day of the Lord” in Zephaniah is that place and time where and when nothing will stand that is not of the living God. This total devastation of systems of power and oppression is not merely temporal and earthly, but carries a level of cosmic totality by bringing us back to the creation narrative. In 1:2–3 we see that the entire created order will be swept away:

I will sweep away humans [adam] and animals; I will sweep away the birds of the air and the fish of the sea. I will make the wicked stumble. I will cut off humanity [adam] from the face of the earth [adama], says the Lord.

Here the framing of the language calls to mind the creation narratives of Genesis 1:26–27, where humans are brought into being and given stewardship and dominion over the face of the earth in Genesis 2:5–9. Zephaniah offers a reversal of Genesis: where God had bound humans to the earth, now the entirety of creation is separated from them, and creation itself is swept away.

Enlarge

Enlarge

A Day That Dawns Bright — a Call to Holiness

While the dies iræ — the day of wrath — has been framed in our cultural imagination by requiems, cinematic apocalypses, and fear-provoking book series about the end of the world, the world does not end this way in the prophesy of Zephaniah. No, as we move into the words of Chapter 3, the prophet turns the day of the Lord from a place of darkness to a dawning of light and hope:

On that day [yôm] you shall not be put to shame

Because of all the deeds by which you have rebelled against me;

For then I will remove from your midst

Your proudly exultant ones,

And you shall no longer be haughty

In my holy mountain.

For I will leave in the midst of you

A people humble and lowly.

They shall seek refuge in the name of the Lord —

The remnant of Israel;

They shall do no wrong

And utter no lies,

Nor shall a deceitful tongue

Be found in their mouths. (3:11–13)

It is as if the narrative of destruction comes to an abrupt halt and turns around to shine a spotlight on a singular reality that is a still point of calm and peace. Here the same day (yôm) of the Lord is now opened to embrace a people who have chosen to walk in the ways of humility, lowliness, and truth. These people are called to a holy life and will bear evidence to the generations of what it means to seek after the Lord, and not their own power and prestige borne on the backs of the oppressed. They shall do no wrongs nor slander in deceit, for their mouths shall be filled with the words of the Lord.

What an amazing promise in the midst of such wrath and destruction. Yes, God takes seriously the work of justice and righteousness, and calls us to turn and face him fully even if it means the end to all that we have previously known and cherished. Yet this same God desires us to live into a life worthy of our calling and not merely be destroyed in the wake of sin. In some respects, this means acknowledging that what we have and what we have become indeed come to an end, and an apocalypse of sorts is on our doorstep.

But, according to Zephaniah, there is still a call to repentance even in the face of doom. “What good will it do,” we might ask, “to turn around and seek a humble and lowly life after we have led a life of brokenness and sin?” As we saw in our Lectio reflections on Jonah a few weeks ago, it is not our job to worry about whether it is worth turning to holiness. Rather, turning to holiness is what we are to do regardless of the outcome. For the city of Nineveh the outcome was so miraculous that even the prophet couldn’t believe the truth of it.

Perhaps this will be your story as well. You may feel that your life has gone so far astray that the wrath of God will be a welcome relief. But perhaps the apocalypse is the easy road and not your calling after all. Why? Because, as we see in Zephaniah, we were meant to sing as our last song not the dies iræ after all, but a song of rejoicing and exaltation found in a life of holiness before the God who embraces and loves:

Sing aloud, O daughter Zion;

shout, O Israel!

Rejoice and exult with all your heart,

O daughter Jerusalem!

The Lord has taken away the judgments against you,

he has turned away your enemies.” (3:14–15)

Questions for Further Reflection

- As you consider the ways in which the dies iræ — the day of wrath — has framed our cultural imagination through music, books, and art, what are some other examples in our modern mass media where this theme of impending doom is apparent? Is it a hopeful or despairing “day of wrath”? What do you think accounts for culture’s interest in these events?

- Zephaniah calls the people to be “humble” and “lowly.” (3:12) Spend some time reflecting on the meaning of those words. Are there any examples of people in your life who embody these qualities? What are some practical ways you could grow in these two areas of life?

- Read again the words of Zephaniah 3:11-20. What stands out to you as a word of challenge? A word of good news? Spend some time in prayer and reflection as you consider the witness of this prophet and its application in your life.

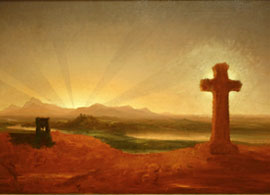

- The artwork for this week’s Lectio is White Crucifixion by acclaimed 20th-century artist, Marc Chagall. This piece is particularly evocative, featuring a juxtaposition of the crucifixion (the embodiment of our hope and redemption) in the midst of despairing and broken people. In what ways do you see this juxtaposition of pain and redemption featured in the prophecy of Zephaniah? Further, in what ways have you seen or experienced this juxtaposition in your own life?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Selections From the Prophets Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

For a lover of the classic requiems this really struck a chord! God is ultimately about grace and hope.

Thanks for your comments – with pun intended I am sure! I agree with you. The power and depth of requiems truly ‘strike a chord’ with us. These master musicians continue to frame the human condition in oh-so-many ways and it is a great way to bring people back to Scripture since so much of classical music (as well as jazz and much of popular music for that matter!) draws inspiration from the living Word.