Hebrews Week 1

A Letter Without a Home: Introduction to Hebrews

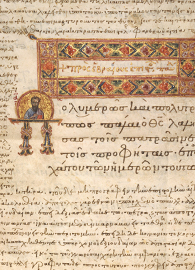

Enlarge

Enlarge

The Letter to the Hebrews is surely one of Scripture’s most enigmatic books. Not only does its language seem strange to us, it is also an orphaned letter that finds a home neither among Paul’s letters (Romans–Philemon) nor among those from the apostolic Pillars of Jerusalem (James–Jude). The Church places Hebrews between these letter collections without even identifying the author. But as frustrating as this may be, perhaps the Church — by the Spirit’s direction — indicates the special role Hebrews performs by its peculiar placement within the biblical canon. More on that possibility later!

Additionally, some students have found that the various comparisons made in Hebrews between the exalted Christ of Christian faith and the key figures and practices of Jewish faith forge a hardened wedge between the two religions, as though the Church had replaced the synagogue in the economy of God’s salvation. This shapes the mistaken belief that trusting Jesus for our salvation requires believers to detach ourselves from the life-giving equipment passed on to us from our Jewish legacy. The worst examples of this unchristian practice deny the authority of Israel’s Scriptures (the Old Testament) and even engage in the racial politics of anti-Semitism.

All this sounds a cautionary note at the beginning of our study together: handle Hebrews with care! Even faithful readers who pick up this letter as God-inspired Scripture are bound to ask, “What is the practical purpose of all the comparisons between Jesus and Jews?”

Modern scholars may be unable to determine the historical setting, author, or audience of Hebrews, but the more important question is this: Why should Christians (and Jews) read this odd letter addressed to the Hebrews as God’s Word for us, right here and right now? To what spiritual crisis does this pastoral letter respond that then underwrites our study with a sense of urgency and importance? This Lectio series seeks to answer these hard questions.

The First Plank: The Relationship Between Scripture and Its Faithful Readers

But let’s begin by building a solid platform of four planks from which to launch our study. Each plank represents one of the most important relationships of a growing Christian faith. The first plank is the relationship between Scripture and its faithful readers. The strangeness of Hebrews makes faithfully studying this portion of Scripture an especially difficult covenant for readers to keep. Martin Luther’s preface to his commentary on Hebrews, written in 1522, captures this difficulty. The great reformer downgrades the letter’s spiritual authority for three reasons, each of which identifies an interpretive cue that, ironically, may help us read Hebrews as God’s Word.

Luther’s First Reason: Authorship

(1) Luther recognizes that Hebrews is a book in search of an author. He points out that the letter itself claims no author, and so its reception as an apostle’s letter is uncertain. Some ancient scholars credit Paul with authoring the letter — including St. Chrysostom, whose commentary on Hebrews remains one of the finest ever written.

Luther rightly judges Chrysostom incorrect for reasons the letter itself points out. Besides notable differences between the letter’s theological conception and Paul’s gospel, Hebrews 2:3 suggests its author and first recipients received their gospel from apostolic eyewitnesses of the historical Jesus. This recognition conflicts with Paul’s own defiant words, registered in Galatians, that his gospel was not given to him by those who knew Jesus but that he instead received his gospel directly from the risen One (Galatians 1:11–12).

Moreover, if Hebrews intends to convey the themes of Paul’s mission to Israel — a commission that Acts both mentions (Acts 9:15) and narrates — we should expect a letter that responds to the controversies which his mission provoked among the Jews (cf. Acts 21:21). But nowhere does the author (we’ll name him “the Preacher”) mention circumcision as a covenant marker, nor does he reject the authority of Israel’s Scripture — in fact the opposite is true.

This debate about authorship, however, prompts an interpretative cue. A biblical book doesn’t need to be written by an apostle (or prophet) to be inspired by the Spirit as Scripture. Put differently, the actual writer of Scripture doesn’t determine Scripture’s importance. Unlike Chrysostom, Origen deferred the question of authorship as something “God only knows.” Early on, Hebrews circulated with Paul’s letters, but by the time the New Testament canon was fixed in its final form toward the end of the fourth century, the Church’s spiritual leaders (including Jerome and Augustine) had received Hebrews as Scripture but denied that Paul had written it. That is, the Church’s recognition of this letter’s inspiration was based upon the orthodoxy of its content and the usefulness of its teaching in forming the Church [see Author’s Note 1].

Even today, passages from the book’s famous central section (Hebrews 7–10) are read during Holy Week as commentary on the atoning death and exaltation of a priestly Messiah. Some of our best-known hymns are full of allusions to Hebrews. Consider the concluding line from Charles Wesley’s great anthem of the faith, “And Can It Be That I Should Gain”: “bold I approach th’eternal throne, and claim the crown through Christ my own,” which echoes Hebrews 4:16. John Wesley preached on Hebrews 6:1 more than fifty times — more than on any other biblical text. It is that text which frames his most urgent pastoral exhortation — not only to remind Christians that the threat of sin still persists, but also to stress the need to press on beyond their new birth and cooperate with God’s sanctifying grace to live like Christ.

One final comment about Luther in this regard: the prefaces to his various commentaries on biblical books retain a catechetical focus. Luther’s suspicion about the inspiration of Hebrews is again related to its teachability. If a text is not easily taught, it cannot easily mediate the word of the living Christ to His disciples. Luther’s claims of Scripture’s authority are grounded in his firm conviction that Scripture, if truly Spirit-inspired, must be used in the teaching and preaching of the Church. If a text doesn’t preach, it can’t be Scripture! Luther’s overriding concerns about Hebrews, then, are not those of modern academic historians; they are practical and have to do with the capacity of Scripture to communicate God’s Word to God’s people. That’s what this Lectio series is all about!

Luther’s Second Reason: Literary Genre

(2) Luther recognizes that Hebrews is a book in search of a literary genre. Luther comments that Hebrews reads like “an epistle of many pieces put together but does not deal with any one subject in an orderly way.” Modern criticism sometimes states that Hebrews lacks structural coherence such that no point flows neatly into the next. This makes it difficult for the reader to track the Preacher’s homily. While I disagree with this literary criticism, again Luther cues something important: faithful readers must identify a biblical book’s genre and become familiar with its literary architecture in order to read it well. Let’s consider this now.

The form of the title given to this letter early in the canonical process, “To the Hebrews,” located it within Pauline letters all similarly titled (e.g., “To the Romans,” “To the Galatians”). While Hebrews functions like a Pauline letter to instruct and correct its readers, its literary form is actually not at all like a Pauline letter. We must hunt down another literary genre — a different kind of architecture to order our interpretation of Hebrews as God’s Word.

Fortunately, Hebrews provides us with the decisive clue, especially when read with Acts. The Preacher actually tells us what kind of book he has written in the letter’s conclusion: “bear with my word of exhortation, for I have written to you briefly” (13:22). Put to one side that the author thinks Hebrews is a brief writing (!). He tells us what Hebrews is: a “word of exhortation.” This is exactly what Luke calls Paul’s speech in the synagogue of Antioch according to Acts 13:15.

Upon closer analysis of Paul’s speech in Acts, we find a number of structural parallels between Paul’s “word of exhortation” and Hebrews. In fact, Bill Lane suggests that this phrase, “word of exhortation,” is a technical term for the kind of rabbinical sermon Jews would likely hear in the synagogues [see Author’s Note 2]. Notice the Preacher combines “hearing” and “writing,” which implies that Hebrews is a written sermon meant for public reading and hearing. While this ancient practice is true of most New Testament writings (e.g., Revelation 1:3), its use in Acts and Hebrews nicely underscores the kind of literature we’re studying: this letter is a Preacher’s homily performed during Sabbath worship at the neighborhood synagogue.

Several implications follow. The literary structure of Hebrews flows like a sermon. The Preacher moves from point to point, each secured by scriptural evidence, pastoral exhortation, and vivid illustration, to persuade a congregation of his pastoral concerns. Wesley likewise founded a tradition in which core theological beliefs and related pastoral concerns are set out in written homilies to be read (and reread) aloud. Like Hebrews, Wesley’s sermons are theological expositions that respond to a crisis of faith or a doctrinal dispute that threatens the spiritual formation of his congregation. I will also follow this design in this series.

Luther’s Third Reason: Practical Divinity

(3) Luther recognizes that Hebrews is a book in search of a “practical divinity” (as Wesley would call it). In particular, he (with many others) objects to the theological sense of the Preacher’s warnings interspersed throughout his homily (e.g., Hebrews 4:4–8; 10:26–31; 12:12–17), which seem to suggest that Christians can forfeit their salvation (and so refuse God’s saving grace) by giving up on Christ. Once saved, always saved? Hebrews suggests not. In Luther’s mind, Hebrews therefore disagrees with St. Augustine’s reading of St. Paul (in which Luther and other reformers firmly stood) by contending that baptized believers can sin in such a way that makes it impossible for God to restore them into covenant fellowship. According to Augustine, God’s electing grace cannot be abrogated!

While Tertullian (with many others) loves the stern rigor of these warning passages and accepts them literally as God’s Word, their tone offends Luther. Luther greatly admires the Preacher’s “masterful” exposition of the theological meaning of Christ’s existence, and the “fine and rich” use of the Old Testament, but he rejects the Preacher’s exhortations as subversive to the reign of God’s grace. While I think Luther is mistaken, his handwringing is useful as a final interpretive cue.

In Luther’s mind, the Preacher’s pastoral exhortation is separate from his Christological exposition rather than being a single piece. We will learn to read this letter from beginning to end as a full-throttle celebration of the Son’s incarnation. The spiritual effect of believing and really owning that Jesus is God’s Son is to end any threat to our faith and to motivate an enduring faithfulness to God as embodied in Christ. The Son has no rival for our affection and affirmation. There is no intellectual argument sufficient to reverse the confidence we place in his Word. God’s incarnation, witnessed and preached by the apostles, realizes every biblical promise, settles all bets, ends all arguments, satisfies every longing of mind and heart, and so is utterly and completely sufficient not only for our salvation but for our entire existence.

To own this belief as the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth yields a dividend of life that confidently hopes for kingdom come. In other words, the Preacher’s exposition clarifies that the “warning passages” are ironic to faithful Christians, whose lives of obedience preclude worrying about such a warning. What other response to the incarnate, exalted Son of God, who is the faithful Pioneer and Sanctifier of our faith, could be more reasonable than our loyal love for him?

EnlargeThe Second Plank: The Relationship Between Old and New Testaments

EnlargeThe Second Plank: The Relationship Between Old and New Testaments

The second plank of our reader’s platform regards the relationship between the Old and New Testaments. I was taught in seminary that any good sermon is an exposition of Scripture, and Hebrews is certainly an exposition of Scripture. In this case, the Preacher’s Scripture is the synagogue’s Scripture in Greek translation (called the Septuagint). Studying Hebrews well will require us to record its conversation with Scripture, moderated by the Preacher’s core beliefs about Christ, who recalls Israel’s biblical story, to warrant and elaborate his word of exhortation addressed to us.

Two important properties of all biblical books were determined during the process of canonization: their titles and their locations within Scripture. Book titles typically serve a theological rather than an historical purpose. That is, rather than identifying who wrote a book or the congregation that first received and read it, titles provide Scripture’s readers with interpretive cues. For this reason, I think the letter’s given title, “To the Hebrews,” does not identify the audience — first century Jewish Christians — but rather serves as a theological marker that guides Christians who read this letter as Scripture. That is, the title recalls the biblical story of Israel as the community of “Hebrews” (see Exodus 1–2) with whom God chooses to covenant and whom God promises to favor.

Since God’s choices are irrevocable, the letter addresses Christians as “Hebrews” to frame the words of exhortation in the memory of Israel’s God as covenant-maker and promise-keeper. This is our story. This is our God. This is our covenant initiated by an act of sheer grace with Sarah and Abraham, confirmed again in the Exodus and on Mt. Sinai, and in the narrative of faithful “Hebrews” (see Hebrews 11), climaxed by the messianic ministry of Jesus, God’s faithful Son (see Hebrews 12:1–6). The Church doesn’t replace Israel; it is the Israel of God’s choosing.

Cued by the letter’s title, then, the Preacher’s unsettling comment that Jeremiah’s prophecy of a “new covenant” (see Hebrews 8; cf. Jeremiah 31:31–34) makes God’s first covenant with Israel “obsolete” (Hebrews 8:13) does not mean that the covenant has been revoked, as though the Church permanently replaces Israel in God’s plan to save the world. Such a view would subvert our core belief in the faithfulness and trustworthiness of God. There is no sense that the Preacher (or the Church’s titling of his homily) understands the incarnation as an act that begins the covenant from scratch with a different people — see God’s angry response to Moses when Israel crafts and worships a golden calf (Exodus 32). God’s reputation is at stake, let alone a people’s salvation! But can unfaithful individuals fall out of covenant based upon their behaviors? You bet [see Author’s Note 3]. Recall that the Exodus generation never saw the Promised Land! The prospect of a renewed covenant is heard by each one of us and our participation in its promised blessings is conditioned on our faithfulness to God’s Word.

Three features of this running conversation with Israel’s biblical story are important to note. First, the Preacher’s use of his Scriptures is ordered by the apostolic witness to the life and work of God’s Son. Every Old Testament text is read as messianic; that is, as a word from God that promises or proclaims what is realized or more fully revealed by Jesus, the incarnate Word. Every prior articulation of God’s Word, whether in creation or in Scripture, continues to reverberate the apostolic witness as interpreted and announced by the Preacher in his word of exhortation.

Second (and this is key), Hebrews is Christian commentary on the Bible’s most elemental, irreducible story of God’s salvation: the Exodus. Scripture’s Exodus narrative plots the normal way God saves people, which not only orders our confession of God’s saving grace (i.e., a faithful God remembers, forgives, and liberates a chosen people held captive by death). But the Exodus story also suggests a prophetic pattern of how a redeemed people works out its salvation in the “wilderness” of its own social locations in hopeful prospect of the Promised Land (i.e., heaven). Hebrews conceives of God’s way of salvation by constant appeal to this biblical typology.

But instead of retaining his readers in the Exodus event as Paul does (read Romans 6), the Preacher moves his readers along into the wilderness where they encounter, as Israel did, suffering and temptation. While their faith is tested, their struggles occasion an awareness of the living Christ’s importance as Pioneer and Priest in guiding their way into the Promised Land. In fact the wilderness journey, not the Exodus, is the essential moment that brings God’s liberated people to the point of recommitment to God as preparatory to a renewal of their covenant with God. Consider, then, this flowchart of the Preacher’s homily. His audience’s struggle to know Christ more fully in order to make their way through the wilderness of the present age (Hebrews 3–7) is prologue to covenant renewal (Hebrews 8–9) and blessings in the age to come (Hebrews 10–12) [see Author’s Note 4].

Finally, one of the most important rhetorical devices Hebrews uses in its exposition of Scripture is comparison; it is featured in a sustained liturgy of praise to the majestic Son whose importance in God’s plan for saving the world is incomparable. What more persuasive way for making this case is there than to compare Jesus with the grand worthy ones of the faith (Hebrews 11) and the covenant-keeping practices of the faith community prior to the incarnation (as described in the Pentateuch — especially Leviticus and Deuteronomy)?

Let me say as sharply as I can that the purpose of these comparisons is not to denigrate the synagogue or to demote the Old Testament in God’s plan of salvation. Rather, the purpose of this strategy is to celebrate Christ in order to emphasize the importance of congregational education: to follow Pioneer Christ into the Kingdom requires the congregation to learn the “solid food” of the incarnate “word of righteousness” that cultivates its capacity to discern right from wrong (cf. Hebrews 5:11–6:3).

The Third Plank: The Relationship of Hebrews to the Rest of the New Testament

The third plank of our platform regards the relationship of Hebrews to the rest of the New Testament. The ambivalence of the ancient Church about whether or not to read Hebrews as a Pauline letter may suggest that its final placement after the Pauline collection indicates that we should study it only after we read Scripture’s Pauline witness. In this sense, we might read Hebrews as though it is a later commentary on Scripture’s Pauline witness. We might think of Hebrews as an appendix that the Church adds to the Pauline canon in order to record some ancillary bits that are not of Paul but nonetheless help us read him more profitably. If we suppose the role of an appendix is to add non-essential but still useful information to our study of a book, then one might imagine that Hebrews is placed where appendices get placed — at the end of a book (i.e., the collection of Paul’s letters) — to clarify details of the Pauline gospel that would be left ambiguous without it.

Many of the Church’s greatest students have picked up and read Hebrews this way. Hebrews pounds out ideas about Christ with which Paul would surely agree but which are not included among his letters, such as Christ’s priestly work, the importance of the Son’s incarnation that Paul rarely mentions, and the relationship between Paul’s gospel and the synagogue. In a manner remarkably different from Acts, one might allow that Hebrews explains the controversies of Paul’s gospel among the Jews even as Romans explains the controversies of Paul’s gospel among the Gentiles. Good material for an appendix!

But a closer consideration of the placement of Hebrews within the New Testament recommends another role. Hebrews is placed between the Pauline collection of New Testament letters and the Catholic (or Pillars) collection written by James, Peter, John, and Jude, to facilitate a formative conversation between them. In this case, Hebrews supplies a glossary of themes that engages Scripture’s reader with a living Word of God, envisioning a manner of discipleship that resists either an only-Pauline or only-Pillars reductionism. Its distinctive and complex portrait of a priestly Christ, for example, has this capacity. Although bits of this portrait recall and interpret a Pauline Christology, especially the centrality of Jesus’s atoning death for putting the faith community into covenant with God, other bits prepare the reader for the Christology of the Catholic Epistles, which depicts his exemplary life — and his suffering in particular — as the pattern of the community’s covenant-keeping.

The Fourth Plank: The Relationship Between Scripture and Theology

A final plank regards the relationship between Scripture and theology. Without a doubt, Hebrews offers readers one of Scripture’s most profound and sustained explorations of Christ’s value in the economy of God’s salvation. Christ is presented as God’s exalted Son whose relationship with God and God’s people brokers a new (or renewed) covenant between them. Not only is the historical Jesus God’s final and most articulate Word for disclosing God’s plan of salvation; He is also the exalted One who enables all those who receive God’s Word in faith to live with God forever.

Typically, discussions of the theology of Hebrews focus on how the Preacher’s theology was shaped by his own time and place as though detached not only from today’s time zones (practical theology) but also from the history of the Church’s confession of its faith (systematic theology). I will try and relate our findings in this Lectio series both to the contemporary practice of our faith and also to the ways in which the theologians of the Church lead us in understanding the various (and sometimes contested) “whats” and “whys” of our creed. In particular, Hebrews reveals important ways of confessing our faith in Jesus as God’s Son, the assurance of our salvation from death because of Him, the manner of human existence and community shaped by Him, and the metrics of the hope we have in the future prepared by God as His and our inheritance.

May God richly bless your study of this inspiring book, God’s Word to God’s people for God’s glory.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Dr.Rob,

Thanks for your clear comments on Replacement Theology, that the Church somehow replaced the Jews as God’s chosen people. There are so many denominations subscribing themselves to this teaching such as the Presbyterian Church USA, United Church of Christ and the United Methodist church. This is a dangerous theology and only goes to further Anti-Semitism, divestment and boycotts of Israel, etc. God bless you brother.

Rob Johnson