Isaiah Week 12

A Return to Justice and Righteousness: Isaiah 56:1–62:12

By Bo Lim

Seattle Pacific University Associate Professor of Old Testament

Read this week’s Scripture: Isaiah 56:1–62:12

13:34

EnlargeDoes Isaiah Love Religion, or Does Isaiah Hate Religion?

EnlargeDoes Isaiah Love Religion, or Does Isaiah Hate Religion?

Religion or activism, which does God truly desire? Recently a video titled, “Why I Hate Religion, But Love Jesus,” which argued that Jesus came to abolish religion, went viral on YouTube. Another Christian responded with a video titled, “Why I Love Religion, And Love Jesus,” which argued that Jesus came to establish religion. So which is true? Is Jesus for or against religion? If Jesus walked this earth today, would we find him praying in a cathedral or occupying Wall Street?

In the first Lectio, I argued that Jesus takes his cue from Isaiah. That is, he models his life and ministry upon the teachings of this prophecy. If that is the case, we ought to consider the question, “What does Isaiah teach regarding religion and activism?” Or in terms more appropriate to the prophecy, “What does Isaiah teach regarding the cult [Author’s Note 1] and social justice?”

One might argue that Isaiah possessed an anti-cultic sentiment and cared instead for social justice. Recall his words in Chapter 1:

What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices? says the LORD; I have had enough of burnt offerings of rams and the fat of fed beasts; I do not delight in the blood of bulls, or of lambs, or of goats. … [B]ringing offerings is futile; incense is an abomination to me. New moon and sabbath and calling of convocation — I cannot endure solemn assemblies with iniquity. (Isaiah 1:11, 13)

Instead, Isaiah urges the people to

Wash yourselves; make yourselves clean; remove the evil of your doings from before my eyes; cease to do evil, learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow. (Isaiah 1:16–17)

In this regard, Isaiah’s message is similar to that of other eighth-century prophets, such as Amos (Amos 5:21–24) and Micah (Micah 6:6–8).

So it appears that for Isaiah, religion is the problem and social justice is God’s true desire for his people. God wants the poor fed, not more animal sacrifices. In Isaiah 40–55, salvation comes in the form of a new exodus rather than a new temple. That is, salvation is to be liberated from bondage, oppression, and famine, and Isaiah hardly mentions the cultic aspects of Israel’s faith. It seems organized religion was Israel’s problem prior to the exile. God liberates Israel from the oppressive idolatry of Babylon, so the last thing on Isaiah’s mind, one would think, would be to reestablish Israel’s cultic religious practices. But is this really the case? That, for Isaiah, God hates religion?

Not quite. What we see in Isaiah 56–62 is that God is not opposed to organized religion. Rather, God’s primary concern is for authentic religion, in which ritual practices carry relative importance and the priority is placed on social justice, inclusive community, and humble piety. This is true religion in the eyes of Yahweh. It’s not an either/or, but rather a both/and. This is the kind of religion that Jesus loves.

New Community

Salvation is not the end, but only the beginning. That is, if Isaiah 40–55 contains a distillation of the gospel, it’s significant that the book of Isaiah doesn’t end with the salvation invitation of Chapter 55:

Everyone who thirsts, come to the waters; and you that have no money, come, buy wine and milk without money and without price.

This invitation initiates us into a way of life described in Chapters 56–66, which leads to a new heaven and new earth. But, before God’s people arrive at that destination, we are to live out our salvation in the present. In the book of Isaiah, the goal of salvation is not merely to free Israel from Assyria or Babylon, but to establish a new community to dwell in Zion. Redemption is not merely about being saved from judgment, but also being saved for obedience.

Because of the work of the servant, described in Chapters 42–53, the scope of Yahweh’s salvation has been expanded. Daughter Zion, who was formerly barren, will now bear numerous children. In Isaiah 54:2, Yahweh announces,

Enlarge the site of your tent, and let the curtains of your habitations be stretched out; do not hold back; lengthen your cords and strengthen your stakes.

That is, the people of God are going to increase such that Israel will need a bigger home to house them.

In a surprising move, in Chapter 56 we learn that the foreigner and the eunuch are among those welcomed into Zion’s tent, the household of God. What is striking about this invitation is that, according to Mosaic law, those whose genitals were cut off, and foreigners, such as Ammonites or Moabites, were not permitted into the assembly to worship God (compare Deuteronomy 23:1–3). According to Mosaic law, foreigners and eunuchs would defile the holiness of the camp.

In addition to exclusion from the community, in Isaiah 56:3 the eunuch laments the fact that he has no future with Israel, because he is impotent and cannot produce children. The startling news Isaiah announces to the nations and outcasts is that they are welcome to enter into the house of the LORD, since it is a “house of prayer for all nations” (Isaiah 57:7) where they possess a lasting inheritance (57:5). They are among the servants of Yahweh and are given priestly responsibilities (57:6) reserved only for the tribe of Levi.

The house of Israel is increasing not only in terms of numbers, but also in terms of diversity. According to Isaiah, the former things have passed and a new thing is springing forth. That includes an Israel that will look very different from the way it looked in former days.

Yet inclusion within the community does place demands on people. Isaiah is not a universalist who believes that everyone, regardless of moral or spiritual commitments, receives salvation. God doesn’t promote inclusivity or diversity for its own sake. Yahweh does not place ethnic or cultic conditions for entrance into the worshipping community, but he continues to require covenantal obedience.

So God does require the foreigner and eunuch to practice Sabbath (56:4, 8) and offer sacrifices (56:7) as manifestations of their religious commitment to Yahweh. God’s invitation is to a holy mountain. Religious practices are a means for God’s people to honor the holiness of God. Just because God is inclusive and generous does not mean God ought to be treated as ordinary and commonplace.

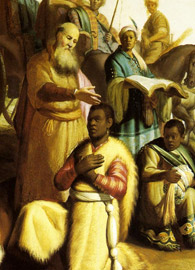

It is no coincidence that Philip encounters an Ethiopian eunuch — who like the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 experiences physical affliction and social exclusion — reading the book of Isaiah in Acts 8:26–40. This foreign eunuch’s baptism indicates that Isaiah’s prophecies are fulfilled in the apostolic mission to the Gentiles. In Galatians 4:27, the Apostle Paul quotes Isaiah 54:1 as support for Gentile inclusion within the church, and in the same epistle he writes,

There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3:28)

Isaiah envisions a new community that will no longer exclude anyone on the basis of race, ethnicity, or disability.

Sabbath and Social Justice

In Week 2 of this Lectio series, I stated that Isaiah 1:27 — “Zion shall be redeemed by justice, and those in her who repent, by righteousness” — summarizes the message of the book of Isaiah. Redemption has been the primary theme throughout Isaiah 40–55. Now in 56:1 we return to the theme of justice and righteousness, and its inextricable relationship to salvation:

Thus says the LORD: Maintain justice, and do what is right, for soon my salvation will come, and my deliverance be revealed.

In order for God’s salvation to be fully realized, injustice must be dealt with — first and foremost its presence among the people of God. Why? Because the goal of Yahweh’s salvation is not the eternal security of one’s soul or merely living a better existence on earth, but rather to be brought to dwell on God’s holy mountain (Isaiah 56:7). Just as the purpose of the first exodus from Egypt was to worship God at Sinai (Exodus 3:12), the Isaianic new exodus announced in Chapters 40–55 leads to the holy mountain of Zion.

One injustice that continues to linger among God’s people is corrupt leadership (Isaiah 56:9–12). Israel’s leaders are lazy, pampered, inebriated, and inept. In addition, idolatry, the fundamental violation of the covenant (Exodus 20:2–6), continues to be practiced in the land (57:1–13). In contrast to the righteous children of daughter Zion (54:1–3), these idolaters are children of a sorceress, adulterer, transgression, and deceit (57:3–4), and engage in immoral and abominable behavior (57:5). They may engage in doing righteousness and good works (57:12), but to no avail, since God desires religious commitment. Social activism alone isn’t enough.

In Isaiah 58:1–14, the problem is the opposite. In this case, the people are practicing some of the religious cultic aspects of the law, but they are grossly violating its ethical obligations. In 58:3b, Yahweh indicts Israel for exploiting her workers on the day of her fasts. The people of Israel might rest and fast on the Sabbath, but their workers are unable to! Their fasting even leads to fighting and violence (58:4a). The people have defined religion within the boundaries of their own comforts. They are willing to entrust their rituals and prayers to God, but not to extend their faith commitment to the social and economic arenas of their lives.

In a shrewd rhetorical move, Yahweh provokes Israel to reevaluate her definition of religion. As noted in Isaiah 58:3, Israel believed that fasting displayed a deep faith commitment to Yahweh. They could not understand how God would not respond to what they considered such a display of faith. Yahweh takes their notion of religion and subverts it by redefining “fasting” in a whole new light. Although they believe they are “seeking” God through their fasts, they forget that Isaiah had earlier clearly instructed that they were to

Seek justice, encourage the oppressed. Defend the cause of the fatherless, plead the case of the widow. (1:17)

To truly “seek Yahweh” is to seek justice and righteousness for the poor and oppressed (compare James 1:27).

Rather than humbling or afflicting itself through fasts done for selfish desires, Israel is now to pour out its soul for the good of the disadvantaged in its community. Israel is to cease from contributing to the problem and to actively work on the solution. This requires Israel to sacrifice its own financial resources, contend for the oppressed in the courts, provide humanitarian aid, and work to dislodge evil and unjust political and economic structures in society.

It is clear that the salvation Yahweh promises is conditioned upon the people’s response. The promises of 58:8–10 are introduced by an “if … then” clause. In 58:10–12, Isaiah announces that, if they feed and care for the hungry and afflicted, light would dawn, a new creation would spring up, and Zion would be reestablished.

What rewards is Isaiah talking about? The promises of light and a New Zion in Isaiah 60–62. Isaiah is not advocating for pure religion and social justice merely for the purposes of improving society. Isaiah is calling for obedience in these areas because it is the means of establishing God’s eschatological order. That is, God’s people are to engage in these ministries because by doing so they participate in bringing about God’s eternal kingdom.

The prophets are not merely anti-ritualists or social activists. Yahweh rejects the worship of the unjust, and requires justice on the day set part for worship. Worship and justice are to be inextricably interrelated.

Sadly in the U.S., Sunday morning worship in many churches continues to be the most segregated hour in our communities. Something is amiss here; we have separated justice from worship. Not only must our ethics inform and infuse our worship, but our worship ought to empower God’s people to be sent out to perform justice and righteousness. God wants activism and worship, not one or the other.

Questions for Further Reflection

- In Chapters 56-62 we have a lot of talk about the cult (e.g., Sabbath keeping and sacrifices). Does God consider these things important?

- Is Christianity a relationship and not a religion? Should the church be involved in social and political causes? Do you think Christians have muddled their priorities?

- What kind of inclusive community does Isaiah imagine? What are the demands placed upon people within this community?

- In what ways does the church need to be more inclusive today, and in what ways does the church need to demand more from its members?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Isaiah Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Thank you, Dr Lim, your thoughts and teaching has been enlightening and challenging. Your summary thoughts add a new dimension to my thoughts re: this beautiful book.

Buzz