Hebrews Week 2

A Sermon’s “Big Idea”: Hebrews 1:1–4

By Rob Wall

Paul T. Walls Professor of Scripture and Wesleyan Studies

Read this week’s Scripture: Hebrews 1:1-4

19:56

Enlarge

Enlarge

Sermons are not easy listening for small kids! I went to church because there were no other options. My parents squeezed me between them, with my two sisters seated on either side of my parents out of harm’s way. Like most young children, I was twitchy during worship, often to the distraction of others — hence my position in our family’s pew where Dad’s strong arm and Mom’s loud whispers attempted to keep my twitchiness to a minimum. For me, the most difficult portion of our worship service, which sometimes ran over two hours, was the sermon. The sermons were long and unintelligible to untrained ears. As I grew older, however, I began to realize the importance of these worship moments when our pastor would preach Scripture in practical ways. Good sermons are formative of Christian faith and life. The exposition of God’s Word remains a congregation’s primary means of God’s sanctifying grace.

Hebrews is one of Scripture’s most powerful sermons, and its implications for Christian faith are equally powerful. For two millennia, faithful preachers have re-preached it, translating and applying its strange but elegant prose. I learned how to craft my own sermons in the seminary classroom of the legendary Haddon Robinson. The first task he gave students was to determine the assigned passage’s “big idea.” Since we were trained to expound Scripture, the big idea we retrieved from a biblical passage then organized our proclamation of God’s Word in an exciting manner formative of a sometimes-twitchy congregation’s life of faith.

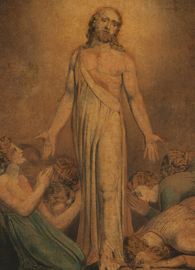

God is Revealed by the Incarnate Son

This week’s passage is a sermon’s big idea, which the Preacher then develops and applies to the life of Scripture’s congregation as a “word of exhortation” (Hebrews 13:22). What readers immediately notice is that Hebrews is a word about God’s incarnate Son. “He is the reflection of God’s glory”; he is the “imprint of God’s very being” (1:3). The Son is the precise articulation of God’s heavenly word through whom the world — past, present, and future — is made and sustained. Simply put, Hebrews celebrates the majesty and incomparable importance of the incarnation of God’s Son, Jesus of Nazareth [see Author’s Note 1]. This is the sermon’s big idea, and it is loaded with practical implications for our lives.

The theological crisis that Hebrews addresses is God’s dilemma: How can our heavenly Father communicate a message of salvation to ordinary folks at ground level? After all, God is divine, not human. God does not experience things humans deal with every day: temptations, sins, foolish choices, and the suffering that often results. God is just not one of us.

From this perspective, we may read the plotline of the Old Testament story as a long series of miscommunications between Israel and Israel’s God. Over and over again, God sanctifies and sends messengers “to serve those who are going to inherit salvation (Hebrews 1:14; cf. 2:16). The Preacher even introduces the letter by noting that “in the past” of salvation’s history, God sent prophets (angels too!) “in many times and many ways” (1:1) to carry God’s Word to God’s people. These prophets reliably revealed God’s plan of salvation and the prospect of lasting shalom (see Hebrews 4) [see Author’s Note 2].

Israel’s routine of spiritual failure could be blamed on the incomprehensibility of God’s message — not clear enough, not hip enough, not practical enough. An even clearer and more relevant articulation of God’s Word was needed so that God’s people might at last understand it, and in understanding believe it, and by believing it receive God’s promised blessings.

And so it is that God sent God’s Son to us “in these final days” (1:2) to communicate more clearly than ever before what has been God’s powerful message all along. The glitch in Israel’s past had been the messenger, not the message. Marshall McLuhan famously asserted that “the medium is the message” [see Author’s Note 3]. In McLuhan’s phrase, Hebrews celebrates the incarnate One as the medium who is the message of salvation.

The Preacher’s phrase “in these final days” is often used in Scripture to indicate a disruptive and decisive moment at the end of human history — when God prepares the world for its salvation, when everything changes, when nothing remains as it once was. Some witnesses (Luke) commend the life and ministry of the Messiah as an apocalypse (i.e., a revelation) of salvation. Other witnesses (Revelation, Paul) look to the Messiah’s any-moment return as an apocalyptic event. Hebrews understands the Son’s incarnation as history’s grand apocalypse: stunning and decisive, an inauguration of “these final days” of world history that brings God’s plan of salvation to its appointed end.

The Son of God Has No Rival

If the Son’s incarnation as a first century Palestinian Jew is God’s way of directing traffic toward heaven, then for those who believe that in him God’s truth is definitively revealed to mediate God’s salvation once for all time, Jesus has no rival. All debate over our intellectual and spiritual options stops dead in its tracks. We accept his teaching as “the way, the truth, and the life” without doubt (John 14:6). If we are persuaded that Jesus is God’s exalted Son, the light of God’s glory, the imprint of God’s being, the mediator of God’s powerful message, the one who cleanses the sinner and heals the brokenhearted, then worship and obedience are our only reasonable responses.

This is the essential argument of Hebrews. It is a longstanding mistake to suppose Hebrews is written to keep Christians in the fold or to defend the Church against threats of heresy. Remember that the exalted Jesus, who is “the imprint of God’s being” (1:3), has no real rivals. And so it is that Hebrews celebrates his effectiveness as the priestly Pioneer of a faithful people who caravan with him toward kingdom come.

The Preacher uses a series of descriptive phrases to concentrate the minds of his congregation on the Son’s majestic persona. The Son is the one whom God makes “heir of all things” (Hebrews 1:2). The Son’s divine appointment comes with “a more important title” than other mediators of divine revelation sent from heaven (1:4). Children inherit their parents’ goods. Naturally, what gets inherited depends on what their parents own. Since God creates everything (as emphasized by the Preacher’s unexpected use of the plural “worlds” in 1:2), the exalted Son inherits everything and so as heir must assume responsibility for everything according to God’s plan of salvation.

Jesus is the one through whom God “created the worlds” — literally the “ages” (1:2) [see Author’s Note 4]. This claim and the letter’s concluding confession that “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever” (13:8) form brackets around its exposition of Christ. Jesus is the instrument God uses to create the entire flow of ages — past, present, and future. He gives shape and direction to the first creation even as His incarnation and exaltation make possible a new creation which puts the world to rights.

The CEB translates the third Greek pronoun, “who,” as “the Son” (1:3), which introduces readers to one of Scripture’s most discussed confessions of who Jesus is. Some scholars argue that the Church’s recognition of Hebrews as Spirit-sanctifying Scripture was based upon the usefulness of this single passage in fighting off Trinitarian heresies early in the Church’s life. It stands as Scripture’s clearest, most evocative expression of the Son’s deity.

That Jesus is the very image of God is the threshold of Christian faith. The real Christian crosses it and owns that what the Church confesses about Jesus is absolutely true on evidence. There is no wiggle room, handwringing, or throat-clearing. Jesus truly is who we confess him to be. And if this is so, every debate over truth ends with an affirmation of Jesus as the “light of God’s glory and the imprint of God’s being” (1:3). Life begins there. Ground zero.

The Preacher’s big idea strikes me as a good foundation for Jesus-followers of the 21st century: confess and celebrate Jesus as God’s exalted Son. Christians have always encountered rival claims of their allegiance. We have always lived in the midst of cultures vying for our ultimate loyalty. Rather than developing extravagant apologetics that defend Christian religion over-and-against other options, Hebrews suggests that we cross the threshold of faith and live into our confession of who Jesus is.

Finally, the syntax of this passage is notoriously difficult but important to unpack. A good commentary on Hebrews will help guide you through this complex linguistic analysis [see Author’s Note 5]. Bottom line: Jesus has a past, which is recorded by verbs in the past tense, but since he “is the same yesterday, today, and forever” (Hebrews 13:8) his past reveals who and what Jesus now is (and has always been) as God’s eternal Son. So, Jesus died in the past to purify people from their sins; He was exalted in the past and received a superior name to other mediators of God’s covenant grace. But what Jesus did and what God did for him “yesterday” cohere with what He has always been and forever will be. That includes right here and now. These majestic claims Hebrews makes about Jesus, then, are continuing markers of a community’s life with Him as our Lord and Savior.

Who do Christians confess Jesus is?

Jesus is “the light of God’s glory” (1:3). God’s glory is always disclosed with special effects. Remember the light and sound show on Mt. Sinai (Exodus 19) or on the Damascus Road (Acts 9)? Those were God’s glory. Folks can see God’s glory; it is a beacon light that signals people to someone or to a message of great importance: the gospel of God’s Son.

Jesus is “the imprint of God’s being” (1:3). This is the phrase that gathered the Church’s first theologians for conversation and debate. There is not another phrase like it in Scripture. Jesus is not only God’s living presence; He is the imprint or engraving of God’s eternal substance for all to see. The Greek noun translated “God’s being” is hypostasis. I like Harold Attridge’s translation of the noun: “fundamental reality” [see Author’s Note 6]. The Son is fundamentally made of the same divine stuff as the Father and the Spirit, the other members of the Holy Trinity.

More critically, however, this is the beginning point in any discussion of Christ. Not His messianic office, not His death on the cross, not His perfect life or victorious resurrection — we start with the confession of who Jesus is: God the Son. It’s not the miracles performed or the suffering endured that counts for our salvation; it’s the divine person who reveals God’s re-creating word. He embodies perfectly the Imago Dei, who died on the cross for our sins, and who cares for us now from heaven’s throne room.

What do Christians claim Jesus does?

Jesus “maintains everything with his powerful message [literally ‘word’]” (1:3). The Lord’s present role as the divine mediator between the triune God and all things (cf. 1 Timothy 2:5–6; Colossians 1:15–20) includes his role in sustaining the created order. This makes sense since God created everything by the same powerful word incarnate in the historical Jesus (see above). The very good intention and direction of creation are personified for “these final days” (1:2) by the powerful word spoken through the Son’s life. The CEB translation of the Greek word rhēma as “message” (1:3) may help readers connect the powerful word Jesus now speaks to sustain the created order with the apostolic memories of what Jesus once said during his messianic mission.

Jesus “carrie[s] out the cleansing of people from their sins” (1:3). This affirmation is also at the epicenter of Hebrews (7:1–10:18): Christ’s priestly self-sacrifice atones for the people’s sins (since he was sinless; Hebrews 4:15) and renews God’s covenant with a forgiven people [see Author’s Note 7]. However, there is a contrast implied between Christ’s death and Old Testament sacrifice: Levitical code requires purification of all contaminated body parts and agricultural products, while Hebrews is more concerned with cleansing the inward spiritual “guts” of a contaminated relationship with God that leads to unholy relationships with each other.

Of course, Christ’s death does more than purify the sinner; it also sanctifies the purified, setting a people apart to do the work of God in the world. The word of exhortation repeated through this sermon drills down here: in denying the importance of Christ’s atoning death, believers reject their capacity to live holy lives, and by doing so make it impossible to belong to God’s covenant-keeping people for whom the promises of eternal life are made.

Why do Christians worship Jesus as our exalted Lord without rival?

Jesus “[sits] down at the right side of the highest majesty” (1:3). Hebrews doesn’t pair Jesus’s death with his resurrection (as Paul does) as the medium of God’s saving work. In this letter the vital pair is Jesus’s death and exaltation, because Christ’s exalted station at God’s right hand is where His pastoral work gets done. The phrase translated “right side” echoes several Old Testament passages that combine priestly and kingly roles to broker God’s victory over the enemies (most strategically in Hebrews is Psalm 110:1, 5). From the “right side” of God’s throne, the Son ensures God’s victory over sin and death (God’s fiercest enemies) by purifying sinners and sanctifying them into a covenant-keeping people.

Jesus “[becomes] so much greater than the other messengers” (1:4). God doesn’t proclaim Himself to people by dispatching non-human angels as carriers of the Word. God sends the Son as the light, the imprint, the carrier of God’s mail, the priestly go-between who cleanses people from their sins and rights them for a covenant-keeping life. Jesus came so that we might become as He is. Jesus is the most practical sermon that goes out to every twitchy pew-sitter. Grace, people, sheer grace.

Questions for Further Discussion

- What do you “confess and celebrate” about Christ in your spiritual communal life? What ideas from these first four verses of Hebrews could you add to your confessions and celebrations in your congregation?

- Dr. Wall suggests that the readers of Hebrews view God as “just not one of us,” and that they may have a hard time understanding how God communicates on “the ground level.” How might this affect their beliefs about Jesus Christ? In your own spiritual life, have you tended to emphasize Jesus’ humanity or divinity, and why? How might reading Hebrews help you to further develop your view of the person of Jesus and the Son’s role in the Trinity?

- What kinds of other allegiances compete for your attention and the attention of your congregation?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Hebrews Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.