Week 7 Wisdom Literature

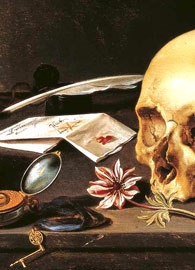

Against Optimism: The Vanity of Life (Ecclesiastes 1:1-4:7)

Seattle Pacific University Professor of Moral and Historical Theology

Read this week’s Scripture: Ecclesiastes 1:1-4:7

18:32

EnlargePoint/Counterpoint

EnlargePoint/Counterpoint

In this Lectio series, we are examining four themes that figure prominently in Old Testament Wisdom Literature. Weeks 2–5 were devoted to the “orthodox” treatment of those themes given in the oldest of the Bible’s Wisdom writings, the book of Proverbs, and Weeks 6–9 to questions and criticisms raised by later Hebrew sages against the orthodox positions.

Last week we studied Psalms 37 and 73 and the Book of Job, and saw how, in squarely facing the problem of evil, the later sages were forced to challenge the prudentialism of the early sages. Today we shall look at the book of Ecclesiastes, and see how, in facing the absurdity and ephemerality of life, it calls into question the moral optimism of wisdom orthodoxy. [Author’s Note 1]

A Hard Book to Like

Ecclesiastes is a hard book to like — or at least it’s an easy book to find reasons to ignore. The ancient rabbis debated whether it should even be included in the canon of Hebrew Scripture, and, although it ultimately cleared that hurdle, it seems to be seldom read during public worship in Jewish synagogues and Christian churches. [Author’s Note 2]

And it’s no wonder religious leaders are reluctant to preach on it. Ecclesiastes is so gloomy, so world-weary, so dubious that the things dear to our hearts — wealth, possessions, honor, pleasure, knowledge — will bring durable satisfaction. With fearless honesty, it asks all the tough questions: does life mean anything? Do I count for anything? Is the daily grind worth the meager and very transitory payoff I seem to get from it?

Ecclesiastes doesn’t quite say no to these piercing questions, but it warns us against that bushy-tailed religious cheerfulness that says yes to them too quickly. We may not like what this book has to say, but its inclusion in the canon is providential. It validates the quest for a faith that refuses to rest content with pious platitudes and superficial pleasantries, a faith that can stand up to the shadow side of human life. We’d do well to spend more time with it.

The Pessimist’s Soliloquy

It’s important to bear in mind that the kind of optimism Ecclesiastes is criticizing is the moral optimism of the early sages. This holds that the world is “rationally ordered and justly governed” by its Creator, and that human wisdom consists in aligning our lives as closely as possible with the divine laws that “map” reality. Moral optimism of this sort is much more tough-minded than what we called “‘Pollyanna’ sentimentality and utopian idealism” (see Week 3), and, while there is little doubt that Ecclesiastes would have rejected these latter varieties if he had encountered them, they weren’t part of the wisdom orthodoxy against which his criticisms are aimed.

His concern was to be even more tough-minded than his predecessors — and this is why his words are at once so disconcerting and so bracing. The early sages had asserted that the universe was rationally ordered. “Well,” he asks, “there certainly are discernible patterns in events — but is there really a discernible purpose to them?”

The early sages had also insisted that the universe was “justly governed.” “Really? Where’s the evidence?” he wonders. Job had already called the traditional reward/retribution scheme into question, but Ecclesiastes goes a step further: “I’m not sure the scheme works, but let’s say it does. So what? Suppose I get the goods I deserve for living rightly — and then find no joy in them. And suppose I do find joy in them. Will it last? Doesn’t the inevitability of death sour my pleasures and mock my accomplishments?”

So he asks. Or, to be more precise, so he asks himself. The theme of this Lectio series is that education aimed at transformation requires conversation. But who is this sage talking to? Not his pupils, not his colleagues, not even God. His inquiries are mostly introspections and his speeches mostly soliloquys. And the only sort of moral transformation taking place here seems to be systematic self-disillusionment. Ecclesiastes — putatively Solomon, the sage-king of Israel — is sitting on this throne, all alone, eating his heart out.

Life as “Vapor”

Ecclesiastes begins his critique of moral optimism with his opening line: “Vanity of vanities! All is vanity!” (Ecclesiastes 1:2). The Hebrew word here translated as “vanity” is hebel. Its literal meaning is “vapor,” or “breath.” Now, the complaint that everything is vapor can be taken in two ways:

- It could refer to the absurdity of things, to their lack of significance, to their hollowness and futility; or

- It could refer to the ephemerality of things, to their lack of substantiality or permanence, to the fact that they all eventually rot, rust, or go up in smoke. (It would not have surprised him to learn that oxygen, which causes all this decay, is a gas!)

In my view, Ecclesiastes used hebel to signify both. He devotes most of Chapters 1 and 2 to the absurdity of things and Chapter 3 to their ephemerality.

The sequence is important. We must first face the emptiness of life, but if we keep our eyes open — Ecclesiastes is an empiricist after all — we begin to notice certain patterns to life, predictable alterations, natural cycles. Things may lack permanence, but there is often some regularity to the changes occurring all around us.

And it is precisely by observing the cyclicity of things — their rising and falling, their waxing and waning — that we begin to detect the hand of divine providence. The universe proves to be divinely ordered — perhaps not morally ordered, but at least wisely ordered. The order may be largely inscrutable to us, but the very fact that we can see cyclicity in things where we first saw only ephemerality enables us to see meaning in things where we first saw only absurdity. Ecclesiastes’ doctrine of time is the clue to his doctrine of value; it is what allows him to reject the moral optimism of his predecessors without lapsing into despair, madness, or atheism. Let’s see how this works.

The Absurdity of Worthy Pursuits and Earthly Blessings (Ecclesiastes 1:12–2:24)

Ecclesiastes first describes his diligent pursuit and successful attainment of human wisdom (1:12–18). Now, the pursuit of wisdom was deemed the noblest of human endeavors, and a country ruled by a philosopher king was thought to be fortunate indeed!

Ecclesiastes doesn’t deny these notions, but, after looking back on his education and his reign, he concludes with a sigh: “In much wisdom is much vexation, and those who increase knowledge increase sorrow” (1:18). Well, if the attainment of wisdom brings only “vexation and sorrow,” maybe sensual pleasure, earthly glory, and great wealth — the delights of fools — will bring happiness. So he plunges into hedonism, only to learn that that, too, is “vanity and chasing after wind” (2:1–11).

Is there no difference between wisdom and foolishness? Ecclesiastes considers this question in the following passage (2:12–23), and comes to a paradoxical conclusion: Yes, there is a difference: “wisdom excels folly as light excels darkness” (2:13). But this is no cause for the wise to indulge in anything as foolish as self-congratulation, for “the same fate befalls” sages and fools alike (2:14). Grinding “toil” is the lot of all human beings, and “vexation” is the inevitable result of their toil — after which they die and leave their earnings to others. At this thought, Ecclesiastes recalls, “I turned and gave my heart up to despair” (2:20).

Well, not quite. For in the very next paragraph, he affirms that a good meal, an honest day’s work, and a fine education come from the hand of God, and are to be enjoyed for what they’re worth. They remain hebel — yet they are also divine blessings, not to be despised. Wisdom consists in regarding good things from both perspectives at once: it would be idolatrous and delusory to overestimate their value, but it would be blasphemous to forget their source or to scorn their intrinsic goodness.

The ability to maintain both perspectives on the value of things depends on having a correct understanding of the temporality of things — their timeliness and their time-boundedness. To this issue Ecclesiastes now turns his attention.

The Cycles of Nature and the Vector of History (Ecclesiastes 3:1–4:7)

“For everything there is a season,” he writes, “and a time for every matter under heaven” (3:1). He then goes on to list 28 “matters” for which there is a proper time (3:1–8). These are organized into 14 pairs of opposites: birth and death, killing and healing, weeping and laughing, and so on. Human life is a complex network of alternations and oscillations, a dizzying play of opposing forces and competing claims.

The immediate effect of all this to-ing and fro-ing is bewilderment at the sheer ephemerality of things. But if we take a step back, we begin to see life as a system of patterned sequences and self-regulating cycles, rather than a crazy quilt of random events. And it is precisely through these cycles and sequences that a kind of orderliness emerges. The daily drill, the weekly round, the monthly pay period, the rotation of the year, and the “seven stages” of human life as a whole [Author’s Note 3] — it all begins to make some sense, and even to look like the work of divine providence.

This poses another problem, however. It may be that nature is a vast array of cycles, and that we ourselves are wheels, or wheels within wheels. But is there any “point” to a wheel? Is life just going in circles? Is it getting anywhere? As usual, Ecclesiastes has an answer, and as usual it’s a cautious, qualified, sadly disillusioned, and yet oddly hopeful answer.

[God] has made everything suitable for its time; moreover he has put a sense of past and future into their minds, yet they cannot find out what God has done from the beginning to the end. I know that there is nothing better for them than to be happy and enjoy themselves as long as they live; moreover, it is God’s gift that all should eat and drink and take pleasure in all their toil. I know that whatever God does endures forever; nothing can be added to it, nor anything taken from it; God has done this, so that all should stand in awe before him. That which is, already has been; that which is to be, already is; and God seeks out what has gone by. (3:11–15)

In other words, God rules nature by means of cycles, and our individual lives are embedded within and largely constituted by these cycles. But for all that, we experience time as something linear. Human history is a vector, with a point of origin, a definite direction, and a final destination.

And our own lives are lived as short stretches of time somewhere along that vector. We are wheels rolling along a few miles of track — a track whose origin is in the unfathomably distant past, and whose destination is in the unforeseeable future. As wheels, we experience rhythms and regularities, not just randomness and ephemerality; but as rolling wheels, we experience directionality, not just indefinite repetition and tedious alteration.

Now, we mustn’t kid ourselves: we won’t get very far. But there is forward movement. And the ultimate destination, though unknown to ourselves, is known to God. Once again we see that for Ecclesiastes a correct estimation of the value of things depends on a correct understanding of their temporality.

A Sad Smile

Ecclesiastes’ message might be summarized like this: “Life is vapor — and thank God.” He’d not say that with a shout, so we won’t add an exclamation point. But he’d say it with a sad and knowing smile, and he’d mean it. God is to be thanked precisely because he has made our lives “absurd” and “ephemeral.” For in so doing, he rescues us from our idolatrous attachment to things and from an inflated assessment of our own importance. By stripping us of our illusions, God enables us to properly appreciate his blessings, to properly enjoy our lives.

Questions for Further Reflection

- The Lectio writer says of Ecclesiastes, “His inquiries are mostly introspections and his speeches mostly soliloquys.” Go back through today’s reading and notice how often he says things such as, “I said to myself” or “I turned to consider.” Where does fearless independent thinking end and neurotic self-obsession begin?

- The Lectio writer also says that the kind of “moral transformation” taking place in this book is “systematic self-disillusionment.” Is that a bad thing? Are we ever entitled to our illusions? What are your illusions about life? Could you do without them? How might you get rid of them, without losing faith, hope, purpose, and meaning?

- When Ecclesiastes says that “all things are hebel,” he is drawing attention to two different aspects of human life — its ephemerality and its futility. How do these differ? In what sense are our lives both ephemeral and futile?

- The author says that human beings are wheels rolling along a few miles of an immensely long track. How is your life like a wheel? Where is it going?

- Reread the last paragraph — and pray about any “idolatrous attachments” you may have, or any “illusions” about yourself or others that you may be harboring.

<<Previous Lectio Back to Wisdom Literature Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.