Week 5 Wisdom Literature

An International Orientation: Proverbs 22:17–24:22; 30:1–33; 31:1–9

Seattle Pacific University Professor of Moral and Historical Theology

Read this week’s Scripture: Proverbs 22:17–24:22; Proverbs 30:1–33; Proverbs 31:1–9

17:24

EnlargeRecapitulation

EnlargeRecapitulation

In the past three weeks we’ve examined the prudential motive that drives the search for wisdom, the optimistic attitude that undergirds that search, and the empirical method by means of which it proceeds. And we’ve seen that these three features of early Hebrew Wisdom Literature were functions of the theological conviction that God’s universe operates in accordance with God’s law, and that God not only expects us to learn and heed his law, but graciously assists us, via the “wooing” of Lady Wisdom, and justly rewards us for doing so, by governing human events in such a way that our best efforts are usually crowned with success.

Today we shall explore a fourth feature of early Hebrew Wisdom Literature, namely its internationalist perspective, and observe the connections of this feature to the other three.

What Do We Mean by “Internationalism”?

In saying that the Hebrew sages had an internationalist perspective, we mean that they were respectful toward, and quite eager to learn from, their counterparts in neighboring nations, such as Egypt, Arabia, Canaan, and Mesopotamia. As we shall see, their intellectual openness was perfectly consistent with their theological convictions, but it is easy to misinterpret or over-interpret that openness, and we must be careful here.

The sages believed that there was but one God — namely, Yahweh, the God of Israel. On this point they were as inflexible as other Hebrew religious authorities. But, whereas the priests and prophets tended to infer from their “Yahwism” [Author’s Note 1] that any religious influence upon Israel would be morally and spiritually corrupting, the early sages drew a rather different conclusion.

The early sages reasoned that precisely because there was but one God, whose wisdom lay at the very heart of creation, anyone who carefully observed human affairs, and abided by the moral laws that everywhere governed human affairs and were everywhere illustrated by them, could attain at least a portion of divine Wisdom. They might not know God by his true name. They might, indeed, believe in a multiplicity of deities. They certainly did not enjoy the special benefits or bear the special responsibilities of the Mosaic covenant. The religious deficiencies of paganism are certainly grave, and the religious superiority of Israel was taken for granted [Author’s Note 2].

But precisely because the moral order established by the one God operates everywhere, the laws by which it operates can be observed by anyone, regardless of nationality — and in the ancient world, religious beliefs and practices were part and parcel of a nation’s identity, and unquestioningly imparted to its citizens — although, admittedly, only Yahwism offered a correct understanding of the true source and deepest meaning of that moral order.

What We Don’t Mean by “Internationalism”

In calling the early sages of Israel “internationalists,” however, we don’t mean they were syncretists, religious universalists, or advocates of world government. Syncretism is the blending of religious beliefs and practices — and often logically incompatible ones — from various sources. The sages of Israel may have adapted proverbs about the wise conduct of daily life from the Egyptians (see below), but that doesn’t mean they adopted Egyptian polytheism, or the various myths and rituals that reflected it.

Universalism is the notion that all religions are equally true — and therefore equally false — such that it is pointless, if not morally wrong, for the representatives of one religion to proselytize the devotees of another. Why try to convert people if, by doing so, you not only cause them to lose a crucial element of their personal and national identity, but introduce them to a worldview that is in no way superior to the one they started with? And the only thing in the ancient world that even remotely resembled the modern idea of world government was the idea of world conquest — something that was out of the question for the tiny nation-state of Israel, whose very autonomy was constantly jeopardized by the superpowers of the time [Author’s Note 3].

No, what is meant here is simply that the early sages of Israel were aware of, interested in, and guardedly favorable toward the wisdom traditions of neighboring nations, precisely because their own convictions about the way in which the universal moral order of God operated prevented them from supposing that they had a monopoly on human wisdom, even if they did enjoy membership in the community with which God had established a special — and exclusive — covenant.

“Foreign” Sages in Israel’s Scriptures

That the Israelites were well aware of the wisdom traditions of their neighbors and quite willing to incorporate quotations from their neighbors’ writings into their own scriptures, can be seen in a number of places in the Old Testament. For example, Proverbs 30:1–9 are ascribed to “Agur, son of Jekeh of Massa” (30:1a); and 31:1–9 is said to be “the words of Lemuel, king of Massa, which his mother taught him” (31:1) [Author’s Note 4].

Massa was reputedly the ancestor of an Ishmaelite tribe from northwestern Arabia, who called themselves by his name (Genesis 25:14; 1 Chronicles 1:30). Independent confirmation of this tribe’s existence is given in Assyrian court records from the eighth century B.C. and in the Geography of Ptolemy, a second-century A.D. scholar from Alexandria, Egypt [Author’s Note 5].

The five disputants in the Book of Job are all non-Jews. Job came from “the land of Uz” (Job 1:1) (probably Edom), and his four comforters from various Arabian towns, tribes, or territories: Eliphaz from Teman, Bildad from Shuah, Zophar from Naamah, and Elihu from Buz (2:11; 6:19; 32:2). One might argue that God’s rebuke of the comforters for failing to “speak of me what is right” reflects an Israelite repudiation of the wisdom of its neighbors. But this argument scarcely holds water, for Job was no less a “foreigner” than his friends, despite their “moral optimism” (which is very much in sync with that of the early Hebrew sages (see Week 3), whereas Job, who had so fiercely challenged God’s justice (as we shall see on Week 6), is praised by God for having “spoken rightly” of him (42:7).

Other passages in the Old Testament highlight the connections among sages from various nations. In 1 Kings 4:30, for example, we learn that the wisdom of Solomon, Israel’s sage-king, “surpassed the wisdom of all the sons of the East and all the wisdom of Egypt.” There is, of course, a pronouncedly nationalistic slant to this passage, but even if Solomon was wiser than the wisest sages of other nations, there is clear evidence here that animated exchanges were taking place among the intellectuals of the various nations in the region.

“Plundering the Egyptians”

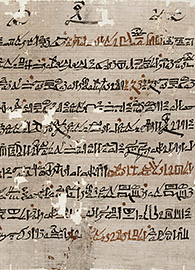

The most striking illustration of the way Israel’s sages made use of the work of their colleagues from other lands is found in Proverbs 22:17–24:22. Admittedly, this passage, which carries the rather vague superscription, “The words of the wise” (22:17a), does not explicitly indicate that it was borrowed from an earlier, and foreign, source. But Bible scholars have long recognized that it adopts and adapts many of the sayings from an earlier Egyptian text known as The Instruction of Amen-em-Opet. The close relationship between the two documents is easily seen by placing some of the relevant lines from The Instruction side by side with those lines in the Proverbs passages that are apparently based on them.

| From The Instruction of Amen-em-Opet | From Proverbs 22:17–24:22 |

|---|---|

| Give your ears, hear what is said,Give your heart to understand them.To put them in your heart is worthwhile,

(But) it is damaging to him who neglects them. Let them rest in the casket of thy belly, That they may be a key in your heart. At a time when there is a whirlwind of words, They shall be a mooring-stake for your tongue. (Chapter 1) |

Incline your ear and hear my words,and apply your mind to my teachings;for it will be pleasant if you keep them within you,

if all of them are ready on your lips. So that your trust may be in the Lord, I have made them known to you today — yes, to you. |

| Do not carry off the landmark at the boundaries of the arable land,Nor disturb the position of the measuring-cord;Be not greedy after a cubit of land,

Nor encroach upon the boundaries of a widow…. Guard against encroaching upon the boundaries of the fields, Lest a terror carry you off. One satisfies god with the will of the Lord, Who determines the boundaries of the arable land. (Chapter 6) |

Do not remove the ancient landmarkthat your ancestors set up.Do not remove an ancient landmark

or encroach on the fields of orphans, for their redeemer is strong; he will plead their cause against you. |

| Cast not your heart in pursuit of riches,(For) there is no ignoring Fate and Fortune….(Or) they [riches] have made themselves wings like geese

And are flown away to the heavens. (Chapter 7) |

Do not wear yourself out to get rich;be wise enough to desist.When your eyes light upon it, it is gone;

for suddenly it takes wings to itself, flying like an eagle toward heaven. (23:4–5) |

| Do not neglect a stranger (with) your oil-jar,That it be doubled before your brethren.God desires respect for the poor

More than the honoring of the exalted. (Chapter 28) |

Do not rob the poor because they are poor,or crush the afflicted at the gate;for the Lord pleads their cause

and despoils of life those who despoil them. (22:22–23) |

Many more examples could be given, but these are enough to indicate the willingness of the early sages of Israel to borrow freely from the insights and experience of their colleagues in neighboring nations, and to imitate the pithy style in which “pagan” wisdom was expressed. Certainly the Israelite sages revised what they borrowed in accordance with their own Yahwistic religious convictions, as the repeated references to “the Lord” bear witness. But the fact remains that they were freely using the literature of their contemporaries for their own purposes.

Conversely, the early sages made scant use of the usual religious “identity markers” of the religion of Israel. In previous weeks we’ve noticed that the Mosaic Law is obliquely referenced in the Book of Proverbs, and certainly the monarchy — or at least King Solomon — features prominently. But little if anything is said about the Patriarchs, the Exodus, the Promised Land, or the Jerusalem Temple. In short, Israel’s distinctiveness vis-à-vis its neighbors, though not denied, is not emphasized.

A Thought to Ponder

What conclusion should we draw from this? Perhaps that the Book of Proverbs serves as a means of rescuing the readers of the Law and the Prophets not only from legalism (see Appendix to Week 4), but also from chauvinism — that is, from the tendency to fixate on national identity and to forget the moral goodness and human decency of neighboring peoples.

Questions for Further Reflection

- What does the Lectio writer mean by saying that the early Israelites had an “international orientation,” and what does he not mean by that?

- Consider the fact that a book of the Bible seems to borrow freely from a surviving Egyptian source. What implications does that have for your understanding of biblical inspiration?

- The form the religious exclusivism took among ancient Israelites was national chauvinism. What forms does religious exclusivism take among Christians? How might the study of Old Testament Wisdom Literature provide a corrective against that?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Wisdom Literature Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.