Week 3 Wisdom Literature

An Optimistic Attitude: Proverbs 8:1–9:18

Seattle Pacific University Professor of Moral and Historical Theology

Read this week’s Scripture: Proverbs 8:1-9:18

15:58

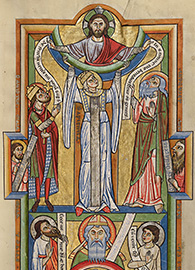

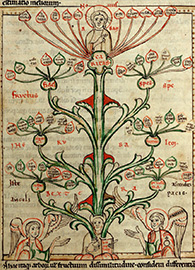

EnlargeRecapitulation

EnlargeRecapitulation

Last week, we looked at the “prudential motive” that the early Hebrew sages offered their students for pursuing wisdom. The sages believed that God’s creation was morally ordered, that this order was knowable to human beings (chiefly via the Mosaic law), that “wisdom” consisted in aligning one’s character and conduct with that divinely established and divinely revealed order, that temporal and spiritual rewards accrued to those who do so, and that justly deserved punishments befell those who didn’t.

We summarized this by saying that those who do good, do well, while those who do bad, do badly. Of course, rewards for obedience and punishments for disobedience are not always immediate: even the most righteous person experiences hard knocks and tough times in life, and the wicked may prosper for a while. But in the long run, God’s justice prevails.

Thus, not only is it wise to be good, but it is comforting for the wise to know that God’s universe is morally ordered and justly governed.

“Optimism” — A Working Definition

We can immediately see that the prudentialism of the early sages is grounded in their profoundly “optimistic” attitude toward life. But it’s important to unpack what we mean by “optimism” here — and what we don’t mean by it. The optimism of the sages was theological and ethical. It was a function of their deep faith in a sovereign and righteous God who has revealed what he expects of us and has promised to reward our best efforts to comply with his expectations.

On the one hand it is cheering to believe that God’s world is rationally ordered and justly governed, but on the other hand it is sobering to think how much rides on our individual and corporate willingness to follow the rules according to which providence operates. The optimism of the Israelite sages must therefore not be confused with “Pollyanna” sentimentality or utopian idealism. The sages did not suppose that all people were basically good and that things always worked out for the best. People must become good — or else! And becoming good takes a lot more time and effort than many people are willing to invest. So the stakes are high and the consequences of failure are potentially dire [Author’s Note 1].

Nor did the sages imagine that human beings possessed, or ever would possess, the know-how to build a heaven on earth. So, while the sages were optimists, they were not “cockeyed optimists” [Author’s Note 2]. They believed in God — not in humanity, and not in good luck. True, the God in whom they believed was intimately involved in human affairs, and could be trusted to do his part in keeping the world running properly, if people would only do theirs.

But there’s the rub. People can’t be trusted to do their part: they must be trained to do their part. And the sages took it upon themselves to provide such training to the young. But precisely because they recognized the untrustworthiness of human beings, they did not imagine that their efforts would achieve much unless God himself somehow took a hand in the process. Enter Lady Wisdom.

Some Gender-bending

Did you notice an oddity in the last two sentences of the previous paragraph? I referred to God himself … and then invoked the figure of Lady Wisdom. The oddity was deliberate, and there are two aspects to it. First, it is odd that the personified divine Wisdom, whom the Bible consistently pictures in feminine terms, should be serving as the personal representative of the God of Israel, whom the Bible usually (though not always) refers to in masculine terms.

Second, it is odd to use any gendered language at all with reference to God — unavoidable, to be sure, but odd none the less. God may be called “Father” — but must not be regarded as “male.” And the personified divine Wisdom may, for the sake of clarity and convenience, be referred to as “Lady” — but must not be considered “female.”

The grammatical conventions governing the use of gendered pronouns tell us nothing about the biological characteristics, if any, of the beings to which those pronouns refer. Sailors will call their ship a “she” without supposing that it is a female. The German word for child, “das Kind,” is neuter, but Germans don’t think that boys and girls lack sexual identity. And the sages call God “he” and Lady Wisdom “she” without supposing that either of them is a biotic entity at all, or that characteristics of maleness, femaleness, androgyny, or sexual neutrality can be properly applied to them.

Lady Wisdom: Not a “Person”… but a Personification

So the sages didn’t regard Lady Wisdom as some sort of female deity [Author’s Note 3]. They understood that wisdom was an attribute of God — like holiness or righteousness — not a separate being. So why did they invest it with “personal,” almost superhuman, qualities? They did so as a way of holding together their optimistic belief that God gives moral order to the universe, and their very realistic appraisal of humans as beings who need divine aid — perhaps even divine inspiration — to live a godly life. They weren’t afraid to give their imaginations free reign when reflecting on the fact that divine wisdom not only governs the universe as a whole, but also seems to become part of the very “heart” or essential personhood of certain individuals. When speaking of God’s “wisdom,” they found themselves referring not only to God’s sovereignty over us, but also to God’s presence among us; not only to divine ultimacy, but also to divine intimacy.

To catch both aspects of this paradox, they personified this divine attribute and ascribed to her a wide array of roles and activities. She is a prophetess who cries aloud in the streets, at the gates, and from the walls (Proverbs 1:20–21; 8:2–3). She is the lover or bride of the sage (3:13–18; 4:4–9; 8:17), his “sister and intimate friend” (7:4), a gracious hostess (9:1–6), and the mother of many children (8:32). She summons human beings to renounce foolish and immoral living and to seek, through companionship with herself, righteousness and the knowledge of God. She bestows “riches and honor, enduring wealth and prosperity” (8:18) on her friends, yet gives them the infinitely more valuable gift of herself — and it is precisely because she gives them herself that they come to understand that she is worth far more than “fine gold,” “choice silver,” and “precious jewels” (3:15; 8:11,19; 31:10). She even announces that she was God’s first creation and the agent through whom God brought everything else into being (8:22–31). Later Wisdom writings developed Lady Wisdom’s persona still further. Ben Sirach treats her as the object of his chaste but ardent love (Sirach 51:13–21), likens her to a wife (15:2b) and mother (4:11; 15:2a), reiterates that she existed before the rest of God’s creation (24:1–34; compare 16:24–30), and affirms her guidance and protection throughout the course of Israel’s history (10:1–19:22). In similar fashion, the author of the Wisdom of Solomon regards her as a lovely bride (Wisdom of Solomon 8:2–21) and a nurturing mother (7:12), affirms her pre-existence (6:22), and traces her hand in salvation history (10:1–12:27). In personifying Lady Wisdom, the sages stretched Israelite Yahwism [Author’s Note 4] as far as it could go without allowing it to lapse into polytheism or evaporate into mysticism.

A Theological Romance

All this poetizing — this ethereal and almost romantic poetizing — serves a very specific theological purpose. It affirms that in order for human beings to become wise, they must finally have God as their teacher, but, conversely, that those who do submit to the tutelage of God not only receive useful training in the art of living, but are invited to participate in the very life of God.

This staggering claim in no way diminishes the value of the instruction given by human sages to their pupils. On the contrary, it elevates the value of such instruction — pragmatic and homespun as it often is — by identifying its ultimate purpose and inner dynamic. For it turns out that God himself, in the persona of Lady Wisdom, stands “above” and “behind” the human sage, as it were, and works through the sage to bring the pupil into a filial relationship with himself. In our two previous lessons, we saw that wisdom teaching is conversational in style and transformative in purpose. This remains true. But now we can see how much more it means than we might previously have suspected.

As for its conversational style, it is no longer merely the sage who tenderly addresses the pupil as “my child” (Proverbs 1:8, 10; 2:1; 3:1, 21; 4:1, 10; 5:1, 7; 6:1, 20; 7:1; etc.): Lady Wisdom does so, too (8:32). And as for its transformative purpose, the down-to-earth guidance given by the sages in right conduct and good etiquette turns out to be nothing less than the means by which young people enter into fellowship with God. “Whoever finds me,” says Lady Wisdom, “finds life and obtains favor from the Lord” (8:35). A later sage will take this a step further: “In every generation she passes into holy souls and makes them friends of God, and prophets; for God loves nothing so much as the person who lives with wisdom” (Wisdom of Solomon 7:27). There is nothing more “optimistic” than that!

Questions for Further Reflection

- According to the Lectio writer, the early sages of Israel took an “optimistic attitude” toward life, but were not guilty of “Pollyanna sentimentality” or “utopian progressivism.” What does he mean by these terms, and what reasons does he give for saying the sages were optimists but not sentimentalists or utopians?

- Read Lady Wisdom’s speech (Proverbs 8:4–36) aloud and slowly. (If you belong to a group study, you might want to assign different parts of the speech to different group members. Natural subdivisions include verses 4–11, 12–21, 22–31, and 32–36.) Then make two lists, one of her personal characteristics (who she is) and one of her functions and activities (what she does). Why do you suppose the author of Proverbs used the literary device of personification to convey his understanding of what is really a divine attribute?

- The writer asserts that it is important to bear in mind that Lady Wisdom is not to be understood as a goddess — that is, as a divine entity distinct from the God of Israel. Why does he think so? Do you agree or disagree?

- One passage in today’s reading assignment not specifically discussed by the writer is Proverbs 9:13–18. It is a sketch of “the foolish woman,” who may in fact be intended as the personification of Folly itself, and thus as a literary foil to Lady Wisdom. Compare and contrast the two figures — where they sit, who they speak to, what they say, etc.

- Christians are “Trinitarian monotheists.” That is, they believe that, although there is but one God, God has three Persons. How does the figure of Lady Wisdom affect Trinitarian monotheism? Do we now have a Holy Quaternity? Or does she simply enrich our understanding of the Father, the Son, and/or the Holy Spirit — and if so, how?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Wisdom Literature Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Thanks Rick for this treatment of Proverbs so far. This segment of scripture makes the most sense when we step back and look at the bigger picture as you are doing. Thanks again!