1 & 2 Samuel Week 2

Eli’s Wicked Sons: Samuel’s Call and the Priestly Fall: 1 Samuel 2:11–1 Samuel 7

Seattle Pacific University Associate Professor of Biblical Studies

Read this week’s Scripture: 1 Samuel 2:11–1 Samuel 7

16:44

EnlargeA Tale of Two Families

EnlargeA Tale of Two Families

Charles Dickens begins his A Tale of Two Cities with the following famous sentence:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way — in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

This week’s section of 1 Samuel also contains a comparison. Instead of a comparison of times or cities, it is a comparison of two families. More precisely, it is a comparison of sons, as the narrative alternates between Hannah’s son Samuel and Eli’s sons, Hophni and Phinehas. One of the contrasts seen most starkly in these two families is how to minister correctly before God and what it means to know God. Samuel is the best of sons, who correctly ministers before God, who knows God and makes God known among the people. Eli’s sons, by contrast, are the worst of sons, and their tragic demise illustrates a larger theological point about God and God’s priests.

The Sons of Eli

These sons of Eli are described as “worthless” (1 Samuel 2:12, RSV), though the Hebrew expression is slightly more poetic: they are “sons of worthlessness.” Hannah uses the same word when she is describing herself to Eli in 1:16, as a description of what she does not want to be. As 2:12 proceeds, it tells us that Eli’s sons are worthless because they do not know God. Such a statement suggests that one’s worth, in part, comes out of knowledge of YHWH. And this is not simply an intellectual knowledge, but a knowledge that is enacted through following and trusting in God. These worthless sons of Eli are not only ignorant of God, but also of the customs and duties of the priests. They take for themselves what is good, in direct opposition to the laws [see Author’s Note 1]. 1 Samuel 2:15–16 says that the people coming to make the sacrifice know more about the proper protocol than Eli’s sons do!

In 1 Samuel 2:23–24, Eli attempts to rebuke his sons, reminding them how serious it is to sin against the LORD. We are told, however, that they do not listen to him because “it [is] the will of the LORD to kill them” (1 Samuel 2:25). We may be shocked by such a statement as well as the matter-of-fact way the Old Testament states it. In the worldview of Samuel, however, God’s will is supreme, God’s power is undisputed, and such a statement did not make the ears of its early listeners tingle as much as it might today. An unnamed “man of God” comes and makes a speech to Eli in 1 Samuel 2:27–36 that confirms God’s plan against Eli’s sons. Though God chose Eli’s ancestors in Egypt to serve as priests (roughly some 250 years before the chronological setting of Samuel), the man of God foretells a time coming (2:31) when they will be cut off, when the sons of Eli both “shall die on the same day” (1 Samuel 2:34).

Eli himself is also indicted for his greed and for his practice of honoring his sons more than God. 1 Samuel 2:30 contains the striking pronouncement, “Therefore the LORD the God of Israel declares: ‘I promised that your family and the family of your ancestor should go in and out before me forever’; but now the LORD declares: ‘Far be it from me; for those who honor me I will honor, and those who despise me shall be treated with contempt.’” God’s past promise is now void. Lest this become a prooftext for God’s unreliability, notice the reciprocity and responsiveness of God, who honors those who honor him and treats with contempt those who despise him. Indeed, it is not only that the sons of Eli are ignorant — they are directly dishonoring, and even despising, God [see Author’s Note 2].

Samuel

Interspersed with these verses about Eli’s sons is the story of Samuel. He is described in terms of what he is wearing (“a linen ephod,” a garment worn exclusively by priests) and what he is doing (“ministering before the LORD,” (2:18) something the sons of Eli are not doing). Samuel’s mother and father visit him annually, and we are given a postscript on Hannah’s life. She has three more sons and two daughters (2:21). The description of Samuel concludes in 2:21 with the statement that he is growing with the LORD, and 2:26 specifies that he is growing “in stature and in favor with the LORD and with the people.”

EnlargeSamuel’s Call

EnlargeSamuel’s Call

Samuel’s call authorizes him as a source of God’s word, which, as 1 Samuel 3:1 tells us, is “rare in those days.” God’s words are connected with visions, as 3:15 suggests. Because both the words of God and visions of God are rare, God’s messengers need both ears to hear and eyes to see. Eli’s eyes are dim, or failing, and while that is a biological description of what happens because of old age, it also has a deeper spiritual meaning. In contrast, Samuel hears God’s audible call (1 Samuel 3:4, 6, 8, 10) and sees God’s vision (1 Samuel 3:15). By the end of chapter 3, Samuel will be recognized by all of Israel as a channel of the word of the LORD (1 Samuel 3:20–21).

Samuel does not initially understand that it is God who is calling him, which likely has more to do with the infrequency of God’s word than with Samuel’s naiveté. God’s call to him is not only audible but also personal, as God calls Samuel by name. Three times Samuel mistakes God’s voice for Eli’s, but it is Eli himself who perceives that the one calling is God (3:8) and advises Samuel to ask God to “Speak, for your servant is listening” (1 Samuel 3:10). The message about the coming punishment for Eli and his sons (3:11–14) is neither a happy nor an easy one [see Author’s Note 3], and Samuel is afraid to tell it to Eli (1 Samuel 3:15). Again, it is Eli who presses Samuel to speak, and Eli responds to God’s message with frank acceptance: “It is the LORD; let him do what seems good to him” (1 Samuel 3:18). It may be that Eli is able to accept this message because he has previously heard it from the man of God in 1 Samuel 2:27–36. Eli, for all his mistakes and faults, is also a man of faith and integrity, which he models for Samuel.

Samuel’s call gives Samuel a difficult message to deliver, especially given his relationship with Eli (who refers to him in 1 Samuel 3:16 as “my son”). This will be a pattern for Samuel, however: God will continue to give Samuel messages that will have harsh effects in the lives of his loved ones and friends, particularly Saul.

The Priestly Fall

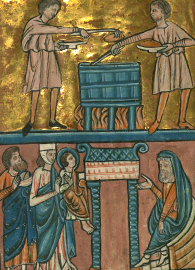

In these chapters, the priests and the ark of the covenant — the container of the tablets of the Ten Commandments — are intertwined. The ark gets captured at the same time that Eli’s sons are killed. But what gets lost will be returned, and the death of one family of priests will lead to leadership from another.

The chapter immediately following Samuel’s call tells us that Samuel is communicating God’s word to Israel at the time when Israel is at war with the Philistines [see Author’s Note 4]. The Philistines win the first battle, killing about 4,000 Israelites (1 Samuel 4:2), so the elders decide to bring the ark of the covenant to the battlefield in order that God “may come among us and save us from the power of our enemies” (1 Samuel 4:3). Their language illustrates that the ark signals the very presence of God; if the ark is on the battlefield, God is on the battlefield and will fight for the Israelites. Because of the sacredness of the ark, the priests would always accompany it. In 1 Samuel 4:4, it is Eli’s sons Hophni and Phinehas who are there with the ark.

The Israelites respond to the ark with a shout so loud that it seems like an earthquake (4:5). The Philistines’ response is one of fear, but that fear motivates them to be brave and to fight harder (4:6–9) — so much so that they defeat Israel! They capture the ark and kill 30,000 Israelites, including Hophni and Phinehas. All this happens very quickly in the text; two verses narrate all this action at a breakneck pace (4:10–11), followed by the information that Eli actually breaks his neck after a messenger tells him the news (4:18). The text makes it clear in 1 Samuel 4:18 that Eli’s death is more directly caused by the mention of the capture of the ark, and less a result of the news about his sons. Death in this family extends to an anonymous wife of Phinehas, who is pregnant and about to give birth when she hears the fate of the ark, her father-in-law, and her husband. As she is dying she names her son Ichabod, which literally means “Where is the glory?” But although the name Ichabod is a question, the text twice makes a statement that the glory has been exiled from Israel because the ark has been taken (1 Samuel 4:19–22).

Where is the Glory?

After capturing the ark, the Philistines take it to the city of Ashdod and place it in the temple of their god Dagon beside a statue of that god (5:2). Strange things transpire: On the first morning, the people discover the statue of Dagon “fallen on his face to the ground before the ark” (1 Samuel 5:3). That pose is one of worship; the Philistine god is bowing down in worship before the ark of the LORD. The people pick Dagon up and put the statue in its place, only to discover the next morning that the statue has not only fallen a second time, but now has its head and hands cut off in a state of utter defeat (5:4). In contrast to the handless statue of Dagon, the text tells us “the hand of the LORD [is] heavy upon the people of Ashdod,” striking them with “tumors” (5:6; in the KJV this word gets translated as hemorrhoids!).

The inhabitants of Ashdod move the ark to the Philistine city of Gath, but those in Gath send it on to the city of Ekron. Panic surrounds these events, and in all places there are tumors and death because the hand of the LORD continues to be “heavy” (5:11). The word translated as “heavy” is the same Hebrew word for “glory,” kabod. Where is God’s glory? God’s hand is “glory” in punishing the Philistines. What may have appeared to be defeat — that the glory has gone into exile — is not ultimately true, for God’s power and glory are exhibited even in this foreign land.

The Return of the Ark

After experiencing tumors and death, the Philistines decide to return the ark to Israel. They also decide to include an offering of gold, for they recall what happened to Pharaoh in Egypt (6:3–6). It is striking that this theologically accurate history lesson comes from Philistine spiritual leaders. Though they are foreigners who worship other gods, they understand the authority and power of Israel’s God. Their language is also significant: they encourage the people to “give glory to the God of Israel” in the hopes that God will “lighten his hand on you and your gods and your land” (6:5). Glory now comes from foreigners. Notably, the word “lighten” (Hebrew qillel) is the opposite of “heavy,” or kabod.

The Philistines are still not certain whether the calamities that they have experienced are directly from the God of Israel, so they devise a method to test God’s involvement. They place the ark on a cart yoked to two milking cows but keep the cows’ calves at home. No one is to lead the cows, but only wait and see where they go. If the cows go to Israel, then the Philistines will know that it was God who made things hard for them, and not just chance (1 Samuel 6:9). Despite the maternal pull — which reminds us of Hannah, who waits to leave her son with Eli until he is weaned (1:24) — the cows walk away from their homes and babies in a direct line to the land of Israel (6:12) [see Author’s Note 5]. The ark arrives at the town of Beth-Shemesh, where it is met with joy and sacrifices (including the poor cows). But some Israelites die, and therefore the people send the ark on to Kiriath-Jearim, a town about 15 miles away from Beth-Shemesh, closer to Jerusalem. The ark stays at Kiriath-Jearim for 20 years under the custody of the priestly family of Abinadab, and under the specific care of Abinadab’s son Eleazar (7:1–2).

Samuel’s Judging

The ark has returned to Israel, and now the text shifts its focus to Samuel as he assumes leadership. Samuel calls “all the house of Israel” to return to the LORD by putting away foreign gods and worshipping God alone (7:3). Samuel also begins to “judge” Israel (7:6), a role that involves both the priestly activities of offering sacrifices and the judicial work of administering justice. Under Samuel, with God’s help, the Israelites are successful against the Philistines as well as with their internal enemies, the Amorites (7:13–14). The boy Samuel has indeed grown up, replacing Eli’s sons as the new leader of his people.

Questions for Further Reflection

- How is God’s character revealed in the events that surround the fall of the house of Eli? How does this portrayal of God challenge you? How does it encourage you?

- When the Philistines capture the ark of the covenant, things do not go quite as they planned. Even though Israel suffered a great defeat, the Philistines do not get to celebrate their victory for long. How do the Philistines respond to God’s “glory,” God’s “heaviness”? How do the Philistines articulate God’s character and actions?

- Samuel emerges as Israel’s leader amid the tragedies of Eli’s family and the captured ark. In what ways does Samuel represent a “new start” for Israel? In what ways does Samuel provide continuity with Israel’s past?

<<Previous Lectio Back to 1 & 2 Samuel Next Lectio>>