Mark Week 5

Expanding Ministry, Growing Opposition: Mark 6:6b–8:21

By Laura C.S. Holmes

Seattle Pacific University Assistant Professor of New Testament

Read this week’s Scripture: Mark 6:6b–8:21

16:34

EnlargeThe Importance of the Exodus

EnlargeThe Importance of the Exodus

For Jews in the first century, there was one primary story that defined their identity and their relationship with God. This story was the narrative of Israel’s exodus from Egypt (Exodus 1–15). If this story is unfamiliar to you, I recommend one of three tasks before beginning this week’s Lectio:

- Read the first 16 chapters of Exodus;

- Read Dr. Frank Spina’s Lectios on Exodus; or

- If you’re feeling nostalgic and love epic films, watch Cecil B. DeMille’s classic The Ten Commandments.

Understanding these next few chapters of Mark requires that readers know the story of the Exodus.

The story of Israel’s deliverance from Egyptian slavery involves five major components.

- The overarching theme of the narrative is about God’s delivering people from bondage. In the first exodus, the bondage is physical captivity in slavery; in Mark, we see Jesus delivering people from many types of captivity.

- God chooses to work through a human leader, Moses, who claims he is unqualified for the position but is able to accomplish great deeds because God has called him and is with him.

- God does not abandon the Israelites during or after their flight from Egypt; images of water and bread signify God’s continual presence with them. In the story of Exodus, these symbolic elements are life itself: The Israelites are able to escape Egypt through parted waters, and they need water in the parched wilderness. They also need food, and God provides bread from the sky.

- The narratives in Exodus 16–19 demonstrate that the Israelites spend much of their time in the wilderness complaining or asking for a sign to prove God’s faithfulness to them.

- Once God has delivered Israel from captivity, God sets out the law to instruct the people how they are to live. In this way, the Israelites are to demonstrate that they are God’s redeemed people by the way they conduct their lives.

Each of these elements (God’s deliverance, human leadership, water and bread, a desire for signs, and the law) appears in Chapters 6–8 in the Gospel of Mark, indicating that Mark expects his readers to understand that Jesus’ actions are taking part in a new kind of exodus. In other words, as we said in Lectio 1, Old Testament Scripture comes to life before the audience’s eyes as the Exodus happens again.

There are more than just Exodus echoes here, however. Mark frames these allusions to the Exodus accounts with narratives about Jesus’ relationship with his disciples, beginning with the positive and concluding with the negative. The interaction between Jesus and the twelve, as well as a broader group of disciples, will become increasingly important as Mark’s narrative progresses.

The Disciples: Commissioning

We know that Jesus has called some disciples (1:17) and that there is a larger group of followers (2:15). Twelve apostles are set apart and named (3:14–19) so that they will proclaim the good news, and have the authority to exorcise demons (3:14).

This week’s first passage in Chapter 6 shows that Jesus imparts his own authority to these 12. They preach, exorcise demons, and heal the sick (6:12–13). They are participants in Jesus’ own mission and ministry involving both acceptance and rejection. We know from 6:12–13 that the disciples’ mission will be successful, but Mark allows us to feel that time has passed by narrating another event between the disciples’ departure and return.

EnlargeExodus Echoes and Questionable Leadership: Herod and Pharaoh

EnlargeExodus Echoes and Questionable Leadership: Herod and Pharaoh

After sending the disciples on their mission, Mark catches his audience up on an event that has already happened. He introduces us to a new character, Herod, whose proper name is Herod Antipas [see Author’s Note 1]. This passage also highlights the first of our connections to the Exodus story: the necessity and challenges of human leadership.

The Exodus parallel begins with a passage that is important primarily because it portrays the inability of a leader to act rightly in the face of pressure from others. In this way, it foreshadows Jesus’ trial and death. Here, we meet up with John the Baptist again. Jesus’ ministry has been linked with John’s since the beginning of Mark’s gospel. Jesus does not start proclaiming the good news until after John has been arrested, and Jesus’ proclamation is very similar to John’s preaching (1:4, 14–15).

Now, John has been arrested on personal charges that run counter to the beliefs of the political establishment, not because he has broken imperial law (6:17–19; 14:55–65). Herod continues to think that John is a righteous man and finds him perplexing, but still listens to him (6:20; 15:1–5). Herod regretfully concedes to John’s gruesome death despite his own wishes, because he does not want to be disgraced in front of his guests. This act foreshadows Pilate’s handing Jesus over to a clamoring crowd, though he knows Jesus is innocent (6:26; 15:9–15).

There is one significant difference between the stories, however. After John’s death, his disciples come, find his body, and give it a proper burial (6:29). Jesus’ disciples will not do the same (15:42–47).

With his lack of strong leadership, Herod exemplifies the need for a different kind of leader. Like Pharaoh in the Exodus story of old, Herod is portrayed as self-absorbed and self-serving, and, even more than Pharaoh, subject to the whims and wishes of others. From Mark’s perspective, it is Jesus who embodies what it means to be a leader like Moses, who will guide the people no matter the cost.

Exodus: Bread in the Desert, Part 1

In fact, we get to see Jesus’ leadership demonstrated in the very next narrative, after the disciples’ return. Jesus and his apostles are about to rest, away from the crowds, just as Jesus himself did in Mark 1:35–36. This time they are stopped by the crowds, and Jesus does not try to escape them again. Instead, he claims that these people are “like sheep without a shepherd” (6:34). This phrase is a quotation from Numbers 27:17 [see Author’s Note 2], and it describes the kind of leader God will raise up to rule Israel. Unlike Herod, who likes the comfort and opulence of the court, Jesus serves as a true leader, teaching and feeding hungry crowds on a hillside.

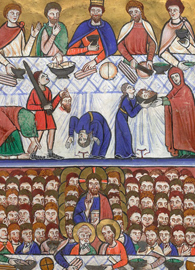

Mark is alluding to the Exodus story by more than just a connection to Moses’ style of leadership, however. In this “deserted place,” Jesus is able to feed 5,000 men, and more women and children, with five loaves of bread and two fish. This miraculous meal looks back to another time when God miraculously fed the people in the desert with bread, or manna (Exodus 16:1–26; cf. 2 Kings 4:42–44 [Author’s Note 3]).

Exodus: Walking on the Water, Not Parting the Sea

The next scene finds Jesus’ disciples again in a boat, preparing to cross the Sea of Galilee. Jesus disappears to pray (on a mountain, like Moses: Exodus 24:15–18), and the disciples find themselves in the middle of another storm (for the first, see Mark 4:35–41). Again, by the end of the scene, Mark has demonstrated that Jesus certainly has power over the chaos of the wind and the waves (6:51). But this evidence of Jesus’ power over chaos is not the focal point of the scene. Instead, we notice the difference: Jesus is walking on water, rather than sleeping in the boat!

Mark notes that Jesus “intended to pass by” the disciples (6:48). To a modern reader, this may seem disturbing: Did Jesus not care about his disciples in the storm? He clearly saw them struggling, so why would he refuse to help? Here, Jesus identifies himself by God’s name (“It is I” in 6:50 translates “I am,” the divine name from Exodus 3:14).

Instead of leading his people through the waters as Moses did (Exodus 14–15), Jesus is more powerful, and walks on top of these dangerous waters. In fact, Mark claims he is like God, who “passes by” Moses (6:48; Exodus 33:19, 22). This new time of exodus looks a lot like the old exodus, but the second leader’s greatness far exceeds the first. Unfortunately, Jesus’ leadership, just like Moses’, faces hardness of heart (6:52; see Exodus 7:3).

Interlude: Legal Issues

In Exodus, after Israel is delivered from slavery in Egypt and is given bread and water in the wilderness, God gives Israel new laws that form the foundation of their relationships with God and with each other. Similarly, after Jesus has demonstrated that he is delivering people from their bondage (e.g., 5:3–4), after he has fed people in the wilderness, and after he proves he is greater than Moses by delivering his followers on the water rather than through the water, he gives a new law.

Such a law is given in contrast to Jesus’ opponents in the gospel, the Pharisees. Generally, the Pharisees would have been considered the most authoritative interpreters of the law, and, therefore, of God’s will. Mark narrates this controversy between Jesus and the Pharisees for several reasons. He shows that Jesus is now the authoritative interpreter of the law; he points out the significance of Isaiah (remember Mark 1:2–3); and he reveals a broadening of the legal restrictions that will allow for the inclusion of Gentiles [see Author’s Note 4].

Jesus critiques the Pharisees by quoting a passage from Isaiah stating that their hearts are far from God, even though they claim to be worshiping and living to honor God. The focus of Jesus’ interpretation of the dietary laws is also the heart. Jesus claims that it does no good to focus on the purity of the food or one’s hands, because the infectious impurities come from inside, not outside, a person. It is impossible to convey how radically Mark is presenting Jesus’ words here.

The focal point, however, lies in the narrator’s aside: “Thus he declared all foods clean” (7:19). This interpretation opens the door for relationships with those who do not observe Jewish dietary practices, which is precisely what happens next.

A New Exodus: Healing Gentiles and Bread in the Desert, Part 2

The next few sections of Mark may seem rather repetitive. There are more healings, another miraculous feeding, and additional echoes of the Exodus. This double cycle of stories is primarily presented to convey one point: what was once given to Israel alone is now also open to the Gentiles. This is an astounding claim! Relationships between Jews and Gentiles, even when both follow Jesus, remain tense and uncertain for many years after Jesus. Mark demonstrates this tension with the difference between the previous story (7:1–23) and the narrative of Jesus healing the daughter of the Syrophoenician woman.

While we have been able to assume that other characters in the Gospel of Mark were likely Gentile because of their geographical location (5:1–20), this woman is the first who is described as a Gentile. Here, Jesus’ comments about cleanliness — or more precisely, holiness — are going to be put to the test. When he meets this Gentile woman whose daughter is demon-possessed, Jesus claims that the “bread” (think about 6:41–44, where bread miraculously multiplies in Jesus’ hands and all are fed) is for the children, the children of Israel, and not for the dogs, a common derogatory term for Gentiles.

This mother becomes the spokesperson for future generations of Gentiles as she claims that dogs, too, get the crumbs that fall from the table (7:28). She does not dispute Israel’s right to be called God’s children; she does not seek to change her role. Instead, she comes to Jesus and claims that there are enough miraculous bread crumbs for all. Even the Gentiles can be clean, says an outsider. Jesus goes on to demonstrate that she is right by healing her daughter, and by healing a deaf-mute Gentile man.

At the end of this passage, the results of this new exodus look very hopeful. Its leader, Jesus, has shown that he can do things even Moses could not, like walking on water. He is delivering people from bondage to illnesses, demons, and sins. He extends this exodus to all, not just to Israel. In fact, Mark 7:37 alludes to part of Isaiah 35, which describes the messianic kingdom, where water springs up in the desert, where eyes and ears and hearts are healed (contrast 4:12; Isaiah 6:9–10), and where God is making a new way that looks a lot like an old way. Unfortunately, there is more story to tell before this hope is fully realized.

A New Exodus: Asking for Signs

After Jesus feeds an additional 4,000 in the wilderness (8:1–10; 6:34–44; see Author’s Note 5), he encounters the Pharisees again, who ask for a sign, just as Israel did in the wilderness (8:11–13; see Exodus 17:1–7; Psalm 95:7–11). This demand for a sign implies that the bread Jesus has provided is not “a sign from heaven.” It also indicates that despite the positive response in Mark 7, perhaps this new exodus will encounter the same problems the first exodus did: the lack of faith of its human participants.

The Disciples: Misunderstanding

This week’s reading concludes with one of the most cryptic passages in the Gospel of Mark. When we began this section, we saw the disciples commissioned with Jesus’ authority to proclaim the good news, to heal the sick, and to cast out demons. Now the disciples are in the boat again, and they are focusing on remarkably mundane concerns. If Jesus can feed more than 5,000 people with five loaves of bread, it makes no sense for them to be worried about not having enough food.

Their anxiety demonstrates what was said of them previously: their hearts have been hardened (6:52). They do not understand, because they cannot understand (8:21). The disciples are going to become progressively more obtuse throughout the rest of the gospel. Like the Pharisees, they do not see the bread as a sign from heaven, nor do they seem to see the significance of Jesus’ actions, heralding this new exodus. Indeed, the disciples and their misunderstanding will become the focus of the next section of Mark’s gospel (8:22–10:52).

A Greater Exodus?

Mark has used the framework of Israel’s foundational story, the Exodus, to show how God is doing something new. Through leadership greater than Moses’, bread given like manna, acts of deliverance in dangerous waters, and a reinterpretation of the law, Mark shows that Jesus has come to deliver his people from all kinds of bondage. However, this deliverance is not yet complete, because people still have trouble understanding, similar to the Israelites’ difficulties in the wilderness. With a greater exodus comes the potential for greater misunderstanding. Now it is not just Jesus’ opponents who are lacking insight; Jesus’ closest associates are also blind, and in need of their own healing.

Questions for Further Reflection

- Why was (and is) the story of the Exodus so important to Jews and Christians? How does Mark’s story of Jesus reiterate or change the events or themes of the first exodus story (Exodus 1–20)?

- What is the effect on us, as readers, when Mark portrays Jesus’ opponents and his disciples as confused about what Jesus is doing? Why would Mark start this section with a positive portrayal of Jesus’ disciples and end with a negative one?

- The middle section of these texts, Mark 7:1–23, describes a legal controversy about how a person is clean — or, we might say, holy. How do you think a person is made holy? How does a person live a holy life?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Mark Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Hi,

I want to thank you for your studies that point to a Jesus of whom we rarely hear in the church… a Jesus who breaks open the categories for ” Israel”, who puts away with the “old signs” of the covenant by broadening the definition of who belongs to the people of God and how they will be recognized ; perhaps understanding that Jesus moved not only beyond Moses but also beyond David and the O.T. promises of land and temple and special election( often translated into privileges for today’s political decisions of the state of Israel) because they were newly defined by him, will enable the church to understand its role in this world better .

What you are setting out and what Jesus lived was clearly taking him to the cross . It will be seen what happens to the theologians and preachers who speak and preach this kind of Jesus.

BLESSINGS!!

What a privilege to follow your studies!

Birgit