Genesis/Exodus Week 11

“God Versus Egypt”: Exodus 5:1–10:29

Seattle Pacific University Professor of Old Testament

Read this week’s Scripture: Exodus 5:1–10:29

21:32

EnlargeThe Israelites’ Plight Goes From Bad to Worse

EnlargeThe Israelites’ Plight Goes From Bad to Worse

The first episode in this section lays the groundwork for understanding issues involved in God’s rescuing of Israel and confrontation with Egypt. Moses and Aaron ask Pharaoh to let the people go into the wilderness to celebrate in behalf of the Lord (YHWH), the God of Israel (5:1). Pharaoh not only denies permission, but completely disregards the Israelite deity: “Who is the Lord (YHWH), that I should heed His voice . . . I do not know the Lord (YHWH)” (5:2). Here Pharaoh indicates that (1) the Israelite deity is at best a minor god and (2) the king is not himself acquainted with this god. Moses and Aaron are rebuffed again in no uncertain terms when they repeat their request.

Not content with merely saying no, Pharaoh also piles more work onto the slave population. From now on the slaves are to produce the same quota of bricks, but have to gather their own straw (5:3–14). By saying that he did not know the Lord, Pharaoh has upped the ante considerably.

This development also leads to Israel’s about-face. When Aaron and Moses first returned to set things in motion, Israel believed and worshipped (4:31). Now they are angry at the turn of events, which has left them worse off than before. They express no confidence in Moses and Aaron, and by implication none in the Lord (5:20–21). Moses, too, reels. He laments that matters have deteriorated since he returned. The divinely orchestrated deliverance seems far away indeed.

At this juncture, the Lord puts everything into perspective. The Lord reiterates the distinctive divine name (YHWH) and at the same time distinguishes it from the name revealed to the ancestors (6:2). But this ostensive change of name is not a simple matter. God reveals that the divine self will be acting in a new way.

To be sure, Pharaoh will be dealt with decisively, and the rescue will take place (6:1). But God’s willingness to take on Egypt and Egyptian bondage represents something different in God’s actions. Israel is not merely to be rescued, but rescued with great divine power against the contrary power of Egypt. When Israel realizes what God is doing, the people will view God differently (6:5–8). Regardless, the people do not yet appreciate this (6:9).

In Exodus, Egypt is more than a run-of-the-mill political state. Instead, it is portrayed as the epitome of human sovereignty, backed up by gods completely identified with the state. This is reflected in Pharaoh’s dismissive question, “Who is the Lord . . . ?” It is equally reflected in the king’s arrogant assertion, “I do not know the Lord” (5:2). The pending contest is between a superpower supported by a pantheon, and disenfranchised slaves possessing no conventional power whatsoever.

So far, the Hebrew slaves have had the support only of the heroic women of Exodus 1–4 and the meager efforts of a Moses who has yet to hit his stride. Given the way the battle is shaping up, it would seem foolhardy to expect the slaves to have a chance. Divine action will change that perception. Egypt’s conventional power is impressive. But it will be no match for the unconventional power of the Israelite deity.

A Genealogy Appears

Two other items need to be factored into our thinking. One is the recitation of a genealogy (6:14–27), which at first seems out of place. But it underscores that the Israelites’ bondage is only temporary, that the growth of the people will continue, and that more genealogies are to come (see the first chapters of Numbers). This genealogy is oriented toward the future.

A second emphasis is that we need to concentrate on God’s action, not on human action. Because of Israel’s disbelief and Pharaoh’s strength, Moses remains reluctant (6:10–13). Even when God prepares Moses and Aaron for their next decisive encounter with Egyptian power brokers, Moses revisits the issue of his poor speaking ability (6:28–30). But God will have none of it (4:14–16; 7:1–2). The God who is in charge will move the plan forward.

But there is still more. The Lord now makes clear what is at stake in this epic confrontation. As the Lord promised, Egypt will soon see signs and wonders (7:3). However, these mighty acts are designed not primarily to coerce Egypt, but to demonstrate God’s power against an ostensible rival sovereignty. Therefore, the Lord will harden Pharaoh’s heart so that he will not let Israel go [Author’s Note 1].

This allows the Lord to make Egypt know who the Lord is, thus reversing what Pharaoh said when first made aware of Moses’ God (5:2). This knowing is not a matter of acquaintance or information. It is a function of understanding the very nature of the God of the Hebrews [Author’s Note 2]. By bringing a devastating judgment on Egypt at the same time as the Lord rescues Israel from slavery, Egypt will know profoundly who God is, who Israel is, and who they are in relation to one another (7:3–5).

We initially recoil at the thought of God’s hardening someone’s heart. Isn’t God in the heart-softening business? Yet this is not a matter of Pharaoh’s or the Egyptians’ free will. This should be seen in the context of contesting sovereignties. God’s hardening of hearts and making people know the divine identity relates to ultimate power. Does power reside exclusively in the powers and principalities represented by great political entities or other socio-political institutions devised by human effort? Or is it located fundamentally and ultimately in the unconventional ways of God and God’s people? Egypt is soon to discover the answer.

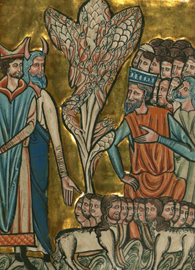

The Lord’s first explicit act against Egypt is most revealing (7:8–24). In accordance with the Lord’s instructions, Moses and Aaron demonstrate divine power by having Pharaoh see Aaron’s rod turn into a serpent (7:8–11). But Egypt’s sages and sorcerers duplicate this feat, thus signaling Egypt’s power. This epic clash of wills has begun. In the end, though, Aaron’s power, derived from the Lord, prevails over Egyptian power (7:11–12).

EnlargeThe Plagues Begin: The Nile Turns to Blood

EnlargeThe Plagues Begin: The Nile Turns to Blood

Still, this display had only minimal effect, in that Pharaoh’s heart had been hardened (7:13–14). The Lord had more to prove. This further proof came in the form of turning the waters of the Nile into blood. The Nile River was a preeminent source of life for Egypt, and, of course, blood is another symbol of life. But, in this case, the Nile’s being turned into blood emphatically signals death. Fish (another source of life) die and people lose a water source (7:15–21). Pharaoh begins to see what he is up against relative to the Lord’s unprecedented power (7:17).

Yet Egypt retains considerable power, as shown when its magicians duplicate this plague (7:22). Of course, by demonstrating this power, the magicians ironically made things worse. Nonetheless, as Egypt suffers, Pharaoh’s heart remains hardened (7:22–24).

The Plague of Frogs

A week later, the Lord instructs Moses and Aaron to threaten Egypt with a plague of frogs (8:1–6). Once more, Egypt’s magicians come through, even though they contribute to the land’s misery (8:7). God’s sovereignty is such that Egypt aids and abets its own demise. This time around, Pharaoh begs Aaron and Moses to ask the Lord to relent.

For the first time, Pharaoh acknowledges Israel’s God (8:8–9). Just as the frogs’ appearance shows the Lord’s power, their subsequent disappearance does likewise. Little by little, Pharaoh becomes aware of what sort of deity he had on his hands (8:10). Nevertheless, the frogs’ removal only gives Pharaoh an excuse to renege. He hardens his own heart on this occasion (8:12–15).

The Plague of Gnats

In response, the Lord sends Moses and Aaron to Pharaoh with the threat of a plague of gnats. At this point, Egyptian power is waning, for the magicians are powerless this time. They even admit that the gnats are God’s doing, about which they can do nothing. But Pharaoh’s still-hardened heart renders him deaf to the Lord’s command (8:16–19).

The Plague of Flies

Flies are the next plague. By now Egypt’s magicians are not even mentioned. Plus, underscoring the Lord’s power, when the flies descend they do not bother a single Israelite. Again, this teaches Pharaoh about Israel’s God (8:20–23). When the flies arrive, they ruin Egypt (8:24). Desperate, Pharaoh offers Israel a chance to worship its God within the land. Moses refuses this concession. Pharaoh counters with a second concession. Israel may leave the land, but not go too far. Moses accepts this condition and prays that the Lord bring the plague of flies to an end. God does so.

In spite of Egypt’s ruin, Pharaoh’s hardened heart causes him to go back on his agreement yet again (8:25–32). Soon there will be no Egypt left to destroy.

The Plague on the Livestock

One more plague — involving cattle — demonstrates both God’s power and the continued hardness of Pharaoh’s heart (9:1–7). That Israelite cattle remain untouched and that God’s timing is exact illustrate the extent of the Lord’s sovereign ability. Egypt remains helpless. Its power is no match for God. In fact, at this juncture something else dawns on us. These plagues all constitute what one scholar has called “creation in excess” (Terence Fretheim). That is, each of them is part of the natural order. From an Israelite perspective, these have all been created by the Lord. From an Egyptian viewpoint, each of these natural entities represents the realms of Egypt’s gods. This is why the plagues should not be considered “natural disasters” in which the timing just happened to work out to Israel’s advantage. Rather, this is God demonstrating sovereignty over both the natural and the political world.

The Plague of Boils

As though to underline God’s increasing power and Egypt’s decreasing ability to deal with it, the next plague affects not only every Egyptian and every animal, but specifically the magicians as well. This strange dust that turns into boils makes the magicians “unable to stand” before Moses. But the sovereign Lord who is responsible for all this continues to maintain an iron grip on the now hapless Pharaoh as well (9:8–12). We clearly see what is taking place. Egyptian people, royalty, magicians, animals, and, by implication, gods, wither before the Israelite deity.

The Plague of Hail

What happens next shows us what is at stake in this business of God’s hardening Pharaoh’s heart and making the divine self known in this particular sovereign display of strength. First off, the Lord has Moses relay the message to Pharaoh that God could easily have destroyed Egypt altogether (9:13–15). Egypt has been spared this ultimate fate so that God could show this extraordinary power and so that the Lord’s name (YHWH) would become known everywhere (9:16). Second, as this next plague is visited upon Egypt, a number of Egyptians now respond by protecting their slaves and animals. These are people who have come to believe in the Lord. Other Egyptians ignore the Lord and suffer the consequences (9:17–21). When this plague descends in the form of a hailstorm, Egypt absorbs an unprecedented blow (9:22–25). Again, so that there could be no mistaking what was transpiring, only where the Israelites lived was there no hail (9:26).

Pharaoh goes so far as to admit his sin to Moses and Aaron, and grant that he and his people have been wrong while the Lord has been right (9:27). The king relents. Moses agrees to implore God to stop the devastation, but also allows that he does not believe Pharaoh (9:28–30). Sure enough, just as Moses thought, Pharaoh goes back on his word yet again. His heart remains hardened (9:31–35).

When God next speaks to Moses, any doubts we might have entertained about the Lord’s strategy are dispelled. The Lord informs Moses that the deity has hardened Pharaoh’s heart and the hearts of his servants, “that I may show these signs of mine among them.” That reason goes along with another: that Israel might tell future generations about God’s sovereignty over Egypt — “how I have made sport of the Egyptians.” This lets both outsiders (Egypt) and insiders (Israel) understand the nature of God (10:1–2).

The Plague of Locusts

Under threat from the next plague — locusts this time — even Pharaoh’s advisors urge him to let the Hebrews go (10:3–7). But Pharaoh is willing to let only certain people out of the land. He then rudely dismisses Moses and Aaron, which naturally triggers the plague and its ruinous effects (10:11–15). Seeing the scale of the destruction, Pharaoh confesses his sin again. Once more, this pseudo-confession gets the plague to cease, but the Lord is not yet done with the king. The deity still hardens his heart (10:16–20).

The Plague of Darkness

The plague of darkness gets Pharaoh to offer another conditional release, insisting that livestock remain in Egypt. Moses rejects this offer, which results in three days of darkness. We would not be incorrect to see in this darkness a return to the pre-creation conditions of Genesis 1:1–2. These “excesses of creation” have all but returned Egypt to primordial chaos. Since the Lord still hardens Pharaoh’s heart, Egypt is all but doomed. Ominously, Pharaoh tells Moses to go away and not bother to return. Negotiations are over. Moses does not protest. He notes that Pharaoh is quite right, for he will not see the king’s face again (10:21–29). Egypt — from the world’s perspective arguably the reigning power and principality — is in the grips of a Power with which it has no way of coping. God is showing a side of the divine self we have heretofore not seen. The future is bright for the Lord’s people. It is both figuratively and literally dark for Egypt and all Egypt represents.

Questions for Further Reflection: Exodus 5:1–10:29

- What problems arise when the various plagues are seen as “natural disasters” or when Israel’s

escape is seen as a slaves’ revolt? - What are the implications of God’s hardening of Pharaoh’s heart or the heart of the Egyptians for a biblical understanding of free will?

- In the light of the text, is the popular valorization of Moses warranted?

- Given the depiction of a powerful God making sport of the superpower Egypt, how might we

conclude that God is good and loving? - What are the implications for coming to grips with the fact that the deity depicted in these Exodus texts is the very deity who is incarnate in Jesus the Christ?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.