Selections From Israel's Story Week 13

Hear and Remember: Deuteronomy 6

By Sara Koenig

Seattle Pacific University Associate Professor of Biblical Studies

Read this week’s Scripture: Deuteronomy 6

15:19

Enlarge

Enlarge

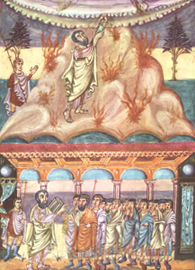

With this Lectio, we move back from narrative to law. In fact, the title of the book, Deuteronomy, means in Greek “Second Law.” It often gets referred to in rabbinic writings as Mishneh Torah, or the repetition of the Torah. That title is a good description of its contents, because Deuteronomy contains a recapitulation of the teachings from Genesis to Numbers.

Deuteronomy takes place after the first generation of Israelites has died (compare Numbers 14), and right before the new generation is — finally (compare Genesis 15:13–21) — going to enter into the Promised Land. But because Moses will not be leading them into the Promised Land (compare Numbers 20), he wants — and needs — to restate God’s instructions for this new generation.

The instructions within this chapter are some of the most basic for Israel, and they express the main theme of the entire book of Deuteronomy: that God demands their ardent and exclusive loyalty. As Deuteronomy 6:5 says, the Israelites are to love the LORD their God with all their hearts, souls, and might.

Within the rest of the book, exclusive devotion to God gets expressed in ways so vehement that they might seem disturbing: Israelites who worship other gods are to be killed, native Canaanites are to be destroyed so that Israel will not be tempted by their gods. In fact, Deuteronomy warns that worship of any other god will lead to Israel’s own destruction and exile from the land [see Author’s Note 1]. But these commands about faithfulness to God need to be read within the context of God’s covenant with Israel, and God’s love for Israel.

Introduction and Instruction

Verses 1–3 are the introduction to the laws in Chapter 6, as well as being an introduction to the laws in Chapters 6–11. Though they are introductory, they are packed with information, and four things stand out.

- We first notice that “the commandment” is referred to in 6:1 in the singular, but it is equated with plural “statutes and ordinances.” In other words, all of these laws (statutes and ordinances) together equal one commandment.

- We then notice that Moses clarifies that these are not his own ideas, but tells the Israelites “the LORD your God charged me to teach you to observe in the land that you are about to cross into and occupy” (6:1). In fact, Moses’ description of the “commandment — the statutes and the ordinances” is the exact terminology God used in Deuteronomy 5:31 (though the NRSV translates the Hebrew there in the plural as “commandments”). By using the same terms God uses, Moses is emphasizing that he is telling Israel exactly what God told him to say.

- We also notice that Israel’s occupation of the land is a fact that is given almost casually. We might skip over that information, had we not read Numbers 13–14. That this generation is about to cross into and occupy the Promised Land is something that their parents certainly did not believe. Moses continues to explain why he is commanded to teach them to observe the commandment: “so that you and your children and your children’s children may fear the LORD your God all the days of your life … so that your days may be long” (6:2). Three generations of Israelites are identified here, but the latter would not be in existence yet. So here is another promise — your children will have children. Your descendants will continue (compare Genesis 13:16; 15:5; 22:17).

- Finally, we notice that these laws, like others we have read this summer, include motivational clauses — promises and reasons for following them. Moses tells the Israelites why they ought to do what God wants them to do: so that their days will be long (6:2), so that it will go well with them, so that they may multiply greatly in the land (6:3).

EnlargeHear and Obey: The Greatest Commandment

EnlargeHear and Obey: The Greatest Commandment

In 6:3, Moses commands Israel, “Hear.” The Hebrew word shemaʿ is repeated in following verse, and in fact, the entirety of Deuteronomy 6:4–9 is a piece of liturgy known as The Shema, the title taken from the first word. However, the word “hear” can and is also translated as “obey.” So “hear” has the sense not only of something auditory: hear, listen; but also of something motivational: obey, do, act.

Deuteronomy 6:4–9 is one of the most significant sections of the entire Old Testament. For our Lectio on Leviticus 19, we noted that Jesus’ “second greatest commandment” came from Leviticus 19:18. His first, and greatest, commandment is taken from Deuteronomy 6:5: love God with all your heart, soul, and might [see Author’s Note 2].

In many ways, the entirety of The Shema is an elaboration of the very first commandment: there are to be no other gods besides the LORD. Deuteronomy 6:4 in Hebrew reads: yhwh ʾeloheinu yhwh ʾechad, or, literally, “the LORD our God, the LORD one.” Rarely is the verb “to be” in its present-tense, “is,” used in Hebrew, so the reader or listener has to supply it.

In this verse, though, it could be added in a number of ways, with slightly different meanings:

- the LORD is our God, the LORD alone (as the NRSV translates it) — a statement about the LORD’s exclusive authority;

- (2) the LORD our God is one — a statement about the nature of God as indivisible; or

- (3) the LORD our God is one LORD — and not many, all of whom go by the name “the LORD” [see Author’s Note 3].

I personally believe that the different possibilities are intentional, that Deuteronomy 6:4 was worded as it was because the implications are all part of worshipping and following this incomparable God.

After commanding Israel to hear — and obey — and after identifying the LORD, the next command is to love. Love is not simply a feeling or an emotional attachment, but it expresses itself in action, as we saw with the commands to love the neighbor and the alien in Leviticus 19. In other words, Israel is supposed to love God by loving and loyal actions to God and others. Still, Deuteronomy is the first book in the Torah to speak about loving God. The previous books emphasize reverence, often expressed through the command to fear God. Deuteronomy includes “the fear of the LORD” (compare 6:2), but includes love as an attitude that should motivate Israel to obey.

How Israel is supposed to love God gets spelled out in more detail in 6:5: “with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might.” These three can be explained in more detail:

- In Hebrew, the word “heart,” levav, usually refers to the interior of the body where thought, intention, and feeling come from.

- The word “soul,” nephesh, is the totality of the person, sometimes understood as “life,” or “being.”

- The word translated “might” is the Hebrew word meʾodekha, which really means “exceedingly,” or “very, very much.”

So, this text asks Israel to love God with its thoughts, its feelings, its life, its existence — a lot. Of course, each one of these is modified with the description “all.” Since the LORD, alone, is God, Israel is to love God with undivided devotion — with all it has and all it is.

From the soaring commandment to love, the text moves into practical details. These words are to be kept in their hearts (again, in their thoughts, intentions, and feelings). They are to be recited — literally “repeated” to their children, spoken about at home and when away, when they lie down and when they rise up (Deuteronomy 6:7).

From this verse, Jews took the daily practice of reciting Deuteronomy 6:4–9 every morning when they woke up, and every evening before they went to bed. The practicalities continue in 6:8–9: “bind them as a sign on your hand, fix them as an emblem on your forehead, and write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.” Certain Jewish groups, including probably the Sadducees, took Verse 8 as figurative, suggesting that one should always be preoccupied with the Torah as if they were on one’s hand or before one’s eyes.

The Pharisees, however, took the text literally, that the words should be inscribed on a scroll that would be placed on the forehead and on one’s hand or arm. Hence the objects known as tefillin, or “phylacteries” — boxes containing words from Exodus 13:1–16, and Deuteronomy 6:4–9 and 11:13–21, with black straps attached to them. The straps are so that the boxes can be wrapped around one’s arm and fit snugly on one’s forehead. The provision in Verse 9 — to write the commands on your doorposts and gates — gets literal expression as a mezuzah, a small case affixed on the doorposts of a house in which is placed a scroll of parchment with the words of The Shema written on it, along with its companion passage, Deuteronomy 11:13–21.

Do Not Forget

The positive reminders are followed in 6:10–15 with warnings against forgetting God. Ironically, it is the blessings and prosperity of the Promised Land that may cause people to forget God. Many of us know, indeed have experienced, that it can be easier to remember God in times of struggle, when we are aware of our need for God, than it is during times of comfort.

In other words, it can be easier to rely on God in the desert than in a land flowing with milk and honey. Even the admonition not to forget God has a reminder attached to it: God is the one “who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery” (Deuteronomy 6:12). This passage revisits the description of God as jealous.

We have read many times this summer about God’s anger burning, and Moses reminds this new generation that God’s anger could be kindled against them (6:15). There is also a reference to the time in the past when the Israelites tested God at Massah (Exodus 17:1–7). The juxtaposition of testing God in 6:16 with the encouragement to obey God’s commandments in Deuteronomy 6:16 suggests that testing God is associated with disobedience.

And once again we see that the commandments are connected with promises and motivations: “Do what is right and good in the sight of the LORD, so that it may go well with you” (Deuteronomy 6:18). Obedience to God’s commandments at this point seems almost a precursor for occupying the land, “so that you may go in and occupy the good land that the LORD swore to your ancestors to give you, thrusting out all your enemies from before you, as the LORD has promised” (Deuteronomy 6:18–19).

Teach Your Children Well

As the chapter ends, it returns to the theme of Deuteronomy 6:7, which emphasized teaching children about God’s instructions. Here, the assumption is that the children will ask about the commandments (6:20), but the answer is to go beyond the value of the individual laws to explain the overall reasons for — and value of — obeying the law overall (6:21–25). It is not clear if the explanation is supposed to be exactly what Moses said, to be recited word for word. But the answer assumes that the parents should know it well enough to answer when they are asked.

Despite the provisions to remember, despite the practical ways to be reminded, we still might forget, especially when the reminders themselves become rote. I have a mezuzah on the doorpost of my office at Seattle Pacific University. One time, a colleague was standing in my doorway talking with me about something else, and she exclaimed, “How beautiful!” My answer — unfortunately — was, “What?”

I had forgotten that it was there. The physical reminder that I had nailed to the entrance to my office was something I had gotten too familiar with, something I walked by without touching, without saying the words of The Shema, without remembering. I often get frustrated with how quickly the Israelites seem to forget God, and then I realize that I am their spiritual descendant. Even reminders apparently do not always help me remember. But in the hearing of the words and the commandments, in talking about them with the family of faith, I am encouraged to keep hearing, obeying, loving, and remembering the God with whom I have a relationship of love.

Questions for Further Reflection

- What does the Lectio writer note as the purpose and main theme of Deuteronomy? Why is it necessary to repeat what God has already done in the history of Israel? Are there ways in which you might begin to more intentionally reflect on your own spiritual journey as a means of continued growth and encouragement?

- A key aspect of the Shema is the practice of repeating and talking about God’s commands. What do you perceive as the value of this? Is there any danger in too much repetition?

- If you do not have a mezuzah, think about another tangible, creative reminder you could make about Israel’s core belief. Share it with someone else.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.