Matthew Week 2

Introducing Jesus: Matthew 1:1–4:17

Seattle Pacific University Professor of New Testament Studies

Read this week’s Scripture: Matthew 1:1–4:17

18:48

Enlarge

Enlarge

Last week I mentioned that Matthew created a gospel characterized by careful organization. In fact, a close look at that organization reveals an amazingly complex set of literary patterns designed to direct our reading of Jesus’ story. Apart from the pattern of shifting between story and sermon described last week, we see that Matthew directs our attention to a particular structure-pattern right away in the genealogy, going out of his way to note that Jesus’ lineage unfolds precisely across three 14-generation stages (1:17).

A truth is hidden in the three-fold pattern: since three 14s equals six sevens, Jesus’ birth inaugurates the seventh of seven generations; and since seven is the biblical number of completion and perfection, Jesus’ birth comes, we might say, in the fullness of time to bring God’s plan to completion (cf. Galatians 4:4–5; Ephesians 1:9–10).

As it turns out, our reading for this week, which sets the stage for the inauguration of Jesus’ ministry (Matthew 4:12–17), can itself be divided into three sections. The first, 1:1–25, might be titled “Who Is the Messiah?” It focuses on names as it traces out Jesus’ lineage and the names given at his birth. Chapter 2 might be titled “Where Is the Messiah From?” It focuses on places as it traces the movements of the child Jesus in order to reveal still more about his identity. The third section, 3:1–4:11, draws the introduction to a conclusion in its consideration of a crucial final question: “What Kind of Messiah Is Jesus?”

Who Is the Messiah? 1:1–25

As we’ve already noted, the genealogy of Jesus in 1:1–17 is designed to set forth Jesus’ royal pedigree. One additional point probably ought to be made about the four Gentile women we were surprised to meet there: all had something sexually scandalous about them that contributed to the outworking of God’s plan to bring forth the Messiah.

Why in the world would Matthew intentionally draw attention to these stories in his articulation of Jesus’ ancestry? Well, we’re about to meet another woman in a similarly scandalous situation: “When his mother Mary had been engaged to Joseph, but before they lived together, she was found to be with child” (1:18).

It is easy for us to forget how shockingly unacceptable this would have been in the first-century world, not just for Joseph and his peers but also for the earliest Christians who preached the gospel. Matthew wants to reassure us: reading Jesus’ story in connection with that of the Old Testament, we are reminded that this is not the first time God has made use of an irregular sexual situation in the long advent of the Messiah.

But where we see connection, we also see disconnection: Mary is “with child by the Holy Spirit.” It turns out that God is the actual “Father,” though Joseph will take him as his own to bind him legally within the lineage of King David. Though the Law required that Mary be put to death for adultery (Deuteronomy 22:23–27), Joseph chooses instead to treat her mercifully.

This is a striking moment, because the only thing we’ve been told about Joseph is that he is “righteous” (Matthew 1:19). Wouldn’t a truly righteous man seek to observe the law to the fullest extent? Yes, of course he would; which is precisely why Joseph treats her with mercy and forgoes the strict letter of the law. Remember this as we read on, for Joseph is our first example of the kind of righteousness Jesus will require of all his disciples.

The angel’s dream-message to Joseph tells us three things to answer the question, “Who is Jesus?” First, Jesus is conceived by the Holy Spirit. Though born by normal means, this baby is conceived out of God and is to be considered “the Son of God,” not the son of Joseph [Author’s Note 1]. Second, Joseph is instructed to name the child Jesus, which is the English version of the Hebrew name Yeshua, “Joshua.”

Three quick sub-points here:

- Though the name means “Yahweh saves,” the angel says “he [Jesus] will save his people from their sins,” suggesting quite clearly that Jesus is going to function as God in bringing forth the promised deliverance.

- He will save people “from their sins,” not from the Roman oppressors as would have been popularly expected of Israel’s Deliverer-King.

- Joshua was Moses’ successor; though Moses gave God’s people the Law, it was Joshua who led them into the Promised Land. In the same way, this Jesus will be presented as the successor to Moses, a “new Moses” who will step in as the authoritative interpreter of God’s law.

Finally, the angel says Jesus will be called “Emmanuel,” which means “God with us” (1:23). As we’ve seen developing across this “naming” section, it is now clear that this Jesus is going to be considered the very presence of God made manifest in the world. This theme of divine presence occurs throughout Matthew’s gospel [Author’s Note 2]; indeed, to form a bookend with this opening “God with us” passage, the gospel will end not with Jesus’ ascension, but with the promise, “I am with you until the end of the age” (28:20).

Who, then, is Jesus? On Matthew’s terms, Jesus is the Son of God, present with us to save us from the power of sin and lead us into the promised land of authentic righteousness.

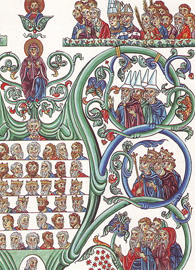

EnlargeWhere Is the Messiah From? 2:1–23

EnlargeWhere Is the Messiah From? 2:1–23

Chapter 2 leads us into further reflection on Jesus’ identity by focusing on place names and geographical movements. We’re told that Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea (2:1). Later, Gentile “magi” from the East arrive just up the road in Jerusalem to ask the existing king of the Jews, King Herod, where they might find the newborn king (2:2).

Again, we’re supposed to note the irony that while Gentile astrologers know of the Messiah’s birth, Herod, the chief priests, and the teachers of the law are ignorant of the fact — though they do have trustworthy scriptures informing them that the Messiah is to be born in Bethlehem (2:4). Herod must rely on the astrologers to find Jesus; they follow the star, find the child, and worship him (2:7–11). Herod also wants to follow Jesus, but not to worship him! So once again God providentially directs the action of the narrative via a dream, instructing the magi to not tell Herod of Jesus’ location (2:12).

Infuriated, Herod seeks to kill Jesus, but, as readers of the Old Testament have come to expect, the worldly king is powerless against God’s plan. Another dream instructs Jesus’ family to escape to Egypt, and the reference to fulfilled scripture (2:15) draws our attention to another important parallel for Matthew. The Hosea quote, “Out of Egypt I have called my son” (Hosea 11:1), draws a connection between Jesus and Israel, the “firstborn son” of God delivered out of slavery in Egypt to be God’s representative people on the earth (Exodus 4:22–23).

Note the many Jesus/Israel parallels that follow: both go from the Promised Land to Egypt and back again, and both encounter kings who kill all firstborn males in an attempt to preserve their power (Exodus 1:22/Matthew 2:16–18). Just as Israel passed through the waters of the Red Sea (Exodus 14), so also Jesus will pass through the waters of baptism (Matthew 3:13–17); and just as Israel’s faithfulness was tested over 40 years in the wilderness of Sinai, so Jesus’ faithfulness will be tested over 40 days in the wilderness of the Jordan (Matthew 4:1–11).

But through all of this connection we once again find an important disconnection: where Israel was unable to fulfill its vocation as God’s servant-representative, Jesus will fulfill that task perfectly. Again, Moses was not allowed to enter the Promised Land, but Joshua was; so also those in this gospel who look to Moses as their authority will not be able to enter into the promised salvation fulfilled in Jesus, the one who is the new Moses and the true king of the Jews.

As the chapter comes to a close we find that though Herod is dead, the political threat of kings in conflict remains (2:19–23). So the royal family is exiled from Judea to settle in Galilee, a region to the north identified as “Galilee of the Gentiles” (4:15). Jesus will proclaim the kingdom in this region all the way until Chapter 19, when the true king of the Jews will return to Judea and head to Jerusalem for the final confrontation with the powers that seek to impede his reign.

What Kind of Messiah Is Jesus? 3:1–4:12

But what kind of reign will Messiah Jesus bring about? The sections that follow begin to answer that question. John is in the “wilderness” (note again the parallel to Israel’s history) preaching, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near” (3:1–2). As the previous chapter introduced us to the king of the Jews, so now John is presented as his royal representative preparing Israel for his arrival.

But John’s call to repent is not a demand to simply express remorse. In biblical context, the word “repent” means to “turn” or “return” to God by acting in faithfulness to the covenant (e.g., Jeremiah 4:1–2; Ezekiel 14:6). John is calling them to return to right relationship with God, because God’s rule is about to be revealed in their midst.

Though we’ve had the story of the Exodus in mind thus far, the reference to Isaiah 40:3 in John the Baptist’s proclamation (Matthew 3:3) calls to mind another of Israel’s wilderness experiences, the punitive exile in Babylon. By Jesus’ day this text was widely applied figuratively to a future moment when God would once again come in power to deliver the people. This “future restoration” theme is underscored by John’s dress, which echoes that of Elijah (3:4; cf. 2 Kings 1:8 and Matthew 11:13–14).

The Old Testament narrative comes to an end with the prophet Malachi saying,

Lo, I will send you the prophet Elijah before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes. He will turn the hearts of parents to their children and the hearts of children to their parents, so that I will not come and strike the land with a curse (Malachi 4:5–6).

By dressing up like Elijah and calling people to turn back to God, John is announcing that the prophesied day of God’s arrival is at hand in the coming of Jesus.

But when representatives of the Jewish leadership arrive (3:7–12), John goes out of his way to clarify that the restoration to come will not look like their current religious practice. The criterion of God’s judgment will not be ethnic or religious identity but evidence of an obedient life that produces “good fruit.” Messiah Jesus, it turns out, is not only a king unlike the current King Herod; he is also a teacher of Israel unlike the current religious leadership.

He is also unlike John, who prepares for the kingdom by baptizing with water; the coming one “will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire” (3:11), notions that would again call to mind biblical imagery of God’s future restoration: the prophet Joel announced that on that day God would “pour out the spirit on all flesh” (Joel 2:28; cf. Acts 2:1–21), and Malachi described God’s coming purification as that of a “refiner’s fire” that would “refine them like gold and silver, until they present offerings to the LORD in righteousness” (Malachi 3:2–3). This Messiah is going to purify his people and give them spiritual power to produce righteousness.

When Jesus, “the coming one,” finally walks out on to the stage (3:13–17), the reader joins John in surprise that Jesus seeks to participate in the baptism of repentance. This is not a Messiah who thinks of power hierarchically, even though John expects him to (3:14). Jesus insists on entering fully into humanity by being baptized as part of a plan “to fulfill all righteousness.”

God’s approval of his action is made clear in what happens next: the heavens are opened, the Spirit comes down upon him, and God proclaims, “This is my Son, the Beloved, with whom I am well pleased” (3:17). The first clause, “This is my Son,” comes from Psalm 2, a royal hymn sung at the coronation of Israel’s king; but that identification is qualified by the rest of the sentence, which comes from the first of Isaiah’s “servant songs”:

Here is my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen, in whom my soul delights; I have put my spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations (Isaiah 42:1).

This servant is the one who is

wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the punishment that made us whole, and by his bruises we are healed (Isaiah 53:5).

He is

the righteous one, my servant” who “shall make many righteous and bear their iniquities (Isaiah 53:11).

This complex introduction to Jesus’ identity comes to focus in the familiar story of the temptation (Matthew 4:1–11). Just as God led Israel through the Red Sea and into the wilderness, so now the Spirit of God leads Jesus, the faithful Israelite, into the wilderness of Judea to be tempted by the devil.

So much could be said here, but let me limit myself to one crucial point. When Satan says “If you are the Son of God,” the issue at stake is not whether Jesus is the Son of God, but what it means for Jesus to take up that role. Will he be the kind of king Israel was used to, the kind who uses his power to serve his own needs (4:3–4)? The kind who tests God’s faithfulness (4:5–7)? The kind who grasps after worldly glory and governing power (4:8–10)?

Jesus’ repeated quotation of passages from Deuteronomy 6–8 makes his intentions crystal clear: in connection with the Old Testament story, this kingly “Son of God” will seek to fulfill the covenant God made with Israel, the “son” brought up out of Egypt to serve God’s plan of bringing redemption to the whole world. A larger view of Jesus’ first reference to Deuteronomy drives the point home:

Remember the long way that the LORD your God has led you these forty years in the wilderness, in order to humble you, testing you to know what was in your heart, whether or not you would keep his commandments. He humbled you by letting you hunger, then by feeding you with manna, with which neither you nor your ancestors were acquainted, in order to make you understand that one does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of the LORD (Deuteronomy 8:2–3).

What kind of Messiah is Jesus, then? In contrast to all other kings of this world, both past and present, Messiah Jesus will humble himself to serve no other interest apart from God’s will. In contrast to the religious leaders of his day, he will institute a religious practice that will conform to God’s standards of righteousness. In contrast to “God’s son” Israel, he will prove faithful when tested and be obedient to the end. He will be the faithful Israelite, the servant-king who will suffer and die in order to bring a salvation of justice and righteousness to the whole world.

Questions for Further Reflection:

- Take a few minutes to identify some of the OT echoes that are referenced in this Lectio. Which of these are notable to you and why? Throughout the author is quoting from and alluding to Israel’s scriptures in order to provide a richer, deeper account of the events of Jesus’ life. How does this persistent, often cryptic “echoing” change your concept of and/or approach to the gospel? To the Old Testament?

- Joseph is our first example of righteousness in this gospel. He expresses this righteousness not by fulfilling the law strictly, but by treating Mary with mercy. What do you typically think of when you hear the word “righteous”? How do you respond to the idea that righteousness ought to be connected to mercy?

- Given what we’ve read thus far, what are we learning about power—both God’s power and the faithful expression of human power?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Matthew Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.