Romans Week 1

Introduction to the Epistle to the Romans

Unparalleled Influence

Perhaps no book of the Bible has had a greater influence on the course of Christianity than Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. The list of individuals who have been associated significantly with this book is without parallel:

- The great church father Augustine had a conversion experience in which he was prompted by a vision of a child who told him to pick up and read Romans 13:13–14.

- The Reformer Martin Luther developed his famous “justification by faith” principle largely from reading Romans and Galatians.

- The revivalist John Wesley had his “heart-warming” experience at Aldersgate at an event where Luther’s Preface to the Letter of St. Paul to the Romans was being read.

- Karl Barth, one of the most prominent theologians of the 20th century, started a theological revolution — one that could resist the temptations and deceptions of Nazi Germany — through his commentary on Romans.

And there have been many others. Those who were responsible for putting Romans immediately after the gospels and the Acts of the Apostles during the history of canonization recognized what had long been the case: Paul’s Epistle to the Romans has had an exceptional place within Paul’s writings, the New Testament, and the Bible as a whole. It is a profoundly important document for Christian identity and belief.

More Than a Letter

A fascinating feature of this epistle is that it is a letter and then some. The work is directed to a specific community at a particular moment in history; it follows conventional letter-writing protocols, as seen in 1:1, 7, and parts of Chapter 16; it shows typical characteristics of a letter and so is markedly different from both the gospel genre (e.g., Matthew, which we looked at during Winter Quarter) and narrative history (e.g., Genesis and Exodus, which we looked at during Autumn Quarter).

And yet it is not a typical epistle, even by the Apostle Paul’s standards. As seen in the break from normal letter writing in 1:2–6, the Epistle to the Romans is mostly a discourse, a “big ideas” document, and so an expansive statement of Paul’s account of Christian belief. This quality has led many to label Romans “the core” or singular summary of Christian theology, thereby prompting its use as a “road to salvation” or its estimation as the darling of the theological academy by being thought of as a “systematic theology” (a work that has all the basic tenets of the faith in an ordered, comprehensive way).

Although Romans is without a doubt an important text, its privileging in these ways has some potentially negative effects:

- First, although Paul covers many of the themes of the Christian faith in Romans, he does not cover them all, nor does he operate out of a concern for comprehensiveness (for example, Paul doesn’t mention the Lord’s Supper in the epistle). Certainly, there is a push to make broad claims about big topics in Romans, but Paul’s aim in this epistle is not to say all that needs to be said about issues of the faith (as a brief glance at other Pauline letters shows).

- Second, Paul would be the first to recognize that he is only one witness to this “gospel of God.” As important as Romans is within Scripture, Paul’s voice is just one of many in the Bible, and part of the beauty of Christian Scripture is precisely the choir of witnesses that it contains. We may have a favorite soloist or a treasured song, but the whole is greater than its individual parts; the “performance of Scripture” would be amiss without James or Revelation or (as is often the case among contemporary Christians) the entire Old Testament. There is spiritual and theological value in the diversity inherent to Scripture, although recognizing this requires passion and diligence.

- Third, the favoritism shown to Romans in particular and Paul more generally by the Western church has had a way of both endearing us further into “what we like,” all the while potentially leading us astray from what we most need. Let me explain: Romans is a heady, large-scale kind of epistle. The West, as evidenced by its philosophical tradition, also likes “big-ideas.” We tend to think that for something to be intellectually sophisticated it has to be abstract, complex, and general. And yet Jesus taught in parables, which are concrete, simple, and specific. Although parables seem like “nice stories” to us, we tend to think that they are not intellectually respectable; therefore, we tend to like Paul’s way of reasoning and thinking better (gasp!) than Jesus’ way of teaching. (I hope you can see what a huge tension this is.)

- Finally, the complexity of Romans beckons a larger framework by which to “connect the dots” in Paul’s thinking. In other words, because Romans is such a complex book, certain Christians read it differently from other Christians in their quest to make sense of what Paul is saying. So, those who emphasize the theme of justification as primary in their account of what salvation is will read Romans differently from those who think salvation is to be best explained by the ideas of new birth and healing.

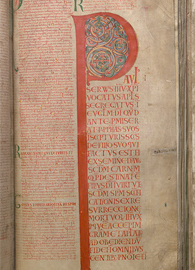

EnlargeApproaching Romans

EnlargeApproaching Romans

If Romans is both so important for Christian identity and yet so complex as to cause it to be read differently by different Christians, how then are we to approach it?

The epistle to the Romans is a letter in which Paul offers his vision of what the God of Israel, the God of Jesus Christ, has done and is doing in the world. In other words, this letter contains a brief, “greatest hits” statement of what Paul believes to be the essential features of the gospel as he understands it at a time in which Christianity was emerging as a religion intricately tied to Judaism and yet having a growing appeal to the Gentile population.

The Epistle gives us an understanding of how Paul, the great apostle to the Gentiles, was negotiating the many tensions that were at play during early Christianity. In the process, he sets out a masterful exposition of a number of very important themes related to the church’s beliefs, witness, and practices.

Why Romans?

But why would Paul write such a letter? Why the “big ideas” approach when talking to specific communities that had specific needs and struggles? Multiple theories have been put forth to answer this question, but some background is important here. Paul most likely wrote this epistle in the 50s A.D. at Corinth (or a region nearby) during a time in his ministry that afforded him the possibility to collect his thoughts. Paul was at somewhat of a crossroads in his ministry. He was longing to go to Spain at one end of the Mediterranean, but he was first planning on going to the other end to visit Jerusalem.

The church in Rome could have played a significant role in these endeavors. Rome would have been an ideal base for expansionist plans, and its resources would have helped Paul. Such support would be easier to secure if Paul would make his understanding of the gospel known, and so the “big ideas” feature of the epistle could have been a strategy by Paul to show the faithfulness of his teachings.

After all, although the epistle does list a number of folks Paul knew who had ties to the Roman churches (Chapter 16), he was still a relative unknown to the area, as the work in Rome was not directly founded by him and he hadn’t visited them at the time of the letter’s writing (1:10, 13).

Nevertheless, Paul must have known about some of the struggles of these churches at the heart of the Roman Empire. Many of these struggles (and much of what Paul deals with in this epistle) revolve around the Jewish/Gentile interface. There was a Jewish population in Rome at the time of Paul’s writing, although plenty of political bans and other social pressures were levied at Jews both before and after the epistle’s composition.

From the clues we have, it seems there were Jews who were part of the early Christian congregations in Rome, but Gentiles constituted significant numbers and perhaps a significant majority (especially since they would not have been subject to the imperial bans). Both groups were living in faith-related tensions. These tensions undoubtedly arose through some very difficult questions, including these:

- What is the role of the law for Jewish and Gentile followers of Christ Jesus?

- What is to be done with Israel’s election as God’s people, especially given how it had been negotiated up to that time?

- Where and how do Gentiles fit into the picture?

Most importantly, what has God been up to all of these thousands of years, from Abraham all the way down to the resurrection of the Messiah, especially if, with the latter, the Gentiles are included in some way?

Such dynamics of negotiating what has gone on before (the history of Israel) with what is happening in Paul’s day (the inclusion of the Gentiles) is intimately tied with the life of the apostle himself. It is easy to forget that at one point in his life, Paul was an avid persecutor of Christians. He believed the early Christians to be heretical and approved of their deaths (as famously reported in Acts 7).

New Answers to Old Questions

And yet, here in the Epistle to the Romans, he is advocating something that earlier in his life he would have found detestable: the inclusion of the Gentiles in Israel. What a turn of events! When Paul says he is crucified with Christ, he is not just saying something platitudinous; he speaks this way out of a reality, one that undoubtedly causes him shame, inspires within him humility, and perhaps creates within him sympathy for his fellow Jews. And yet this gospel occasioned for Paul tortuous forms of physical hardship and persecution (including stonings and lashes).

These many features of his background led him to consider his apostleship with dedication and passion. At one point, he was persecuting fellow Jews for their beliefs in Jesus as Messiah; later, he became the greatest advocate for Gentile Christians among his fellow Jewish Christians. The shift was difficult for onlookers to believe and difficult for Paul to bear. The Jewish-Christian interface is not something that Paul talks about simply; it is the very stuff of his life.

Essentially, Paul is asking many basic questions surrounding Jewish and emerging Christian faith, and turning the traditional answers on their head. Undoubtedly, this quality of asking anew about the basics of the faith has contributed to the impact Romans has had throughout the history of its reception.

Whether the matter relates to personal faith, corporate faith, or an interplay of both, Romans emits a certain kind of aura that appeals to others who sense tensions in their own lives and contexts. What Paul has managed to do is set a course of reasoning and reflection that is unrivaled for its expansive scope and its implications for what Christianity was to become, particularly at a time in which so many of the features of the faith were still being shaped and formed in the life of the church and in the teachings of the apostles.

The Epistle to the Romans represents Paul’s vision of the gospel, of who Christ is and what he has done, and of how this has to change everything.

Questions for Further Reflection:

- This initial Lectio is laying the foundation for our reading of Romans. How does the historical setting of this epistle influence one’s reading? Likewise, how might reading an epistle differ from reading the narrative texts we’ve already encountered in the Lectio this year?

- What are some of the broad-stroke themes to be on the lookout for as we read Romans? Where does the theme of identity fit into the mix?

- Romans has typically held a very important role in the Christian canon. What have been some of your experiences with this letter, and what are you anticipating as we embark on our new Lectio series?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.