Mark Week 1

Introduction to the Gospel of Mark: Mark 1:1–15

Seattle Pacific University Assistant Professor of New Testament

Read this week’s Scripture: Mark 1:1–15

16:57

EnlargeA Redundant Sequel?

EnlargeA Redundant Sequel?

Good news. Death and Darkness. Revelation. Misunderstanding. Miracles. Mystery. Authority. Suffering. All of these contrasting terms characterize the vivid portrayal of the good news in the Gospel of Mark. This gospel tells the story of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection in a way that engages the novice yet intrigues the scholar.

As a Lectio community, the last time we were in the gospels was one year ago, when we read the Gospel of Matthew together. In many ways, Mark’s second place in the canon may feel like a redundant sequel to readers of Matthew: 90 percent of Mark’s narrative is included in the Gospel of Matthew, and much of what is not included in Matthew is material some modern readers continue to deem odd (e.g., 14:51–52).

This overlap between the first two canonical gospels, in particular, poses the question: Why do we need Mark, if Matthew includes much of the same information? To state this problem even more pointedly, Mark is missing much of the material Christians are likely to consider central to the gospel:

- There is no Christmas story.

- There is no Good Samaritan.

- There is no Prodigal Son.

- There is no Sermon on the Mount.

- There are no parables about a humble tax collector and a hypocritical Pharisee.

- In the original text of Mark, it is possible that there was not even an account of the resurrected Jesus appearing to anyone.

So Why Do We Need Mark?

The Gospel of Mark is historically important because it was likely the first gospel written, thus serving as a framework for others. The early church affirmed that it was inspired Scripture. Additionally, there are characteristics that differentiate Mark from the other gospels, as we will see through this Lectio. Essentially, though, what sets Mark apart is not so much what Mark says, but rather how Mark says it.

While Mark’s gospel was likely written first, it is placed second in the canon of Scripture. In one sense, this placement has a historical rationale: for many years, the church saw Mark as an abridgement of Matthew [see Author’s Note 1]. In another sense, a theological purpose may be behind this arrangement.

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus’ disciples are competent followers. While they do not get everything right, and, indeed, betray and deny Jesus at the end, they seem to understand at least some of what Jesus is saying and doing. Mark’s gospel, however, demonstrates the disciples’ remarkable obtuseness from the beginning to the end of Jesus’ ministry (compare Mark 4:13 and Matthew 13:16, 51).

Readers of the Gospel of Mark may oscillate between judgmental surprise that the disciples cannot seem to grasp what Jesus is proclaiming, and compassion as they identify with the struggling disciples in understanding and living the life of discipleship. Reading the Gospel of Mark after the Gospel of Matthew can produce a healthy unsettling of our knowledge. While Mark presents the good news of Jesus Christ (1:1) succinctly, this gospel is not easy, and does not pretend that answers to profound questions are straightforward. There are secure foundations, but there are many mysteries fogging the depths of those foundations.

Introducing Mark

The Gospel of Mark, along with the other canonical gospels, functions as a kind of selective biography of Jesus, telling its audience about Jesus’ adult life, some about his teaching, and a notable amount about his suffering and death. However, the Gospel of Mark does not present a biography of Mark himself. Church tradition associates Mark with John Mark (Acts 12:12, 25) and indicates that Mark based his gospel on the preaching of the apostle Peter and was written for Christians in Rome. Based on the little information we have, it is likely that the gospel was written around the year 70 CE, for a (probably Gentile) Christian community or communities in either Rome or Syria.

Mark is well known for its emphasis on Jesus’ action, rushing from place to place “immediately” (see 1:10, 12, 18, 20, 42). As will become quickly evident, the Gospel of Mark focuses on Jesus’ suffering and death and how this death relates both to Jesus’ identity and to the nearness of God’s kingdom. Mark not only discusses Jesus’ actual trial, suffering, and death in great detail, but also structures his narrative so that this end result is clear as early as Chapter 2 (verses 19–20) and repeats Jesus’ prophecies of his death three times (8:31; 9:31; 10:33–34).

Furthermore, not only is this suffering a facet of Jesus’ life, but it is characteristic of the lives of Jesus’ followers as well (8:34–9:1). Mark is candid about the fact that disciples are often unable to sacrifice to the point to which God calls them. To this end, a central theological claim of Mark, in line with the rest of Scripture, is that God is faithful even — and especially — when humans are not.

At the same time, as we noted above, much about God and Jesus in this gospel is shrouded in mystery. There is no doubt that God’s purpose will be accomplished, but there is much less clarity about how that accomplishment will come about. In this way, Mark portrays Christian disciples walking the life of faith, and mirrors this characterization in the way he tells the gospel story.

The purposes of Mark’s gospel are not stated clearly, unlike the gospels of Luke (Luke 1:1–4) and John (John 20:30–31). Nevertheless, given what we have discerned about Mark’s audience and the material he includes in his narrative, it seems that this gospel serves at least two purposes.

First, Mark is the shortest of the canonical gospels. This relative brevity seems ideal for reminders of the details and fundamental claims of the Christian story.

Concurrently, however, Mark serves a second purpose that may, on first glance, seem at odds with the first. While Mark can offer a basic introduction to the gospel, there is also much beneath the surface for an experienced Christian. In the same way that a budding pianist can learn the locations and names of the piano’s 88 keys in an afternoon, yet spend a lifetime developing the skills of a concert pianist, so the Gospel of Mark serves an important purpose for both the novice and the experienced Christian. Mark can teach the basics while showing us how much more there is to know.

Mark’s Introduction: A Predicted Surprise

The best way to introduce the Gospel of Mark is to let Mark himself acquaint us with the gospel. The first 16 verses of the gospel serve as an orientation to the narrative to come. They highlight some important connections between Jesus, God, and God’s kingdom. Most importantly, these verses emphasize the significance of the Old Testament for understanding Jesus’ ministry, so that the language of God’s good news (“gospel”) is old, even if the news itself is surprising.

Mark begins, not with the birth of Jesus (as Matthew and Luke do), but rather with a general statement of introduction (Mark 1:1) followed by quotations from the Old Testament. Mark contends, as do all the New Testament writers, that one cannot understand Jesus apart from Jesus’ own scriptures, or what Christians call the Old Testament.

Mark’s use of the Old Testament is often subtle, but here Mark signals that he is quoting from the Old Testament, when he says, “as it is written in the prophet Isaiah” (1:2). However, only the second half of Mark’s quotation actually comes from Isaiah. The first part (“Look, I am sending my messenger before you, who will prepare your way”) is a quotation that combines Exodus 23:20 and Malachi 3:1. This misattribution strikes many modern readers as odd, at best.

While there may be many reasons for Mark to begin his gospel in this manner, two reasons stand out as significant for our reading of the rest of the gospel.

- First, it is noteworthy that the book of Isaiah plays a particularly prominent role in the gospel as a whole. Mark quotes from Isaiah at central points in his gospel, and many of the themes of Isaiah seem to be evoked or reenacted in Jesus’ ministry. For this reason, Mark may identify Isaiah as his primary Old Testament prophetic voice simply to call to mind the significance of Isaiah’s prophecies so that the reader is prepared to encounter them in the coming chapters [Author’s Note 2].

- Second, however, there is a theological reason for Mark to conflate other words with Isaiah’s. For Mark, as for New Testament authors as a whole, Old Testament Scripture was a text into which life had been breathed by the Holy Spirit. The Spirit’s presence, in light of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection, now helped the church (of whom Mark is a part) interpret Scripture rightly. To this end, Jesus’ coming has empowered his followers with the ability to read Scripture with open, fresh eyes.

Indeed, one of the new ways in which Mark wants his readers to read the Old Testament involves Scripture’s coming to life before their eyes. John, the baptizer, is introduced by these scriptures in Mark 1:2–3, but his physical appearance and actions bring another figure of the Old Testament to mind: Elijah. Just as Elijah was a prophet in the wilderness who called all Israel to turn back (“repent”) from worshipping the Canaanite god Baal (1 Kings 18:21; 2 Kings 1:8), so John calls “all the country of Judea and all the people of Jerusalem” to repent (Mark 1:5). John’s role is one of preparation. Baptism was a means of purification, of symbolizing the turning aside from one way of life and turning toward a new path.

John, resembling Elijah in appearance and action, has come to prepare the way for someone greater (1:2–3, 7–8). John’s baptism also prepares the way for a greater baptism to come, a baptism by the Holy Spirit. Yet, when we meet Jesus in the Gospel of Mark, he is given the briefest of geographical introductions (“from Nazareth of Galilee,” 1:9), and Mark describes Jesus’ submitting to John’s baptism.

In this way, Mark’s brevity in narrating Jesus’ baptism focuses less on John (we already know he thinks Jesus is superior to him: 1:7) and more on Jesus’ relationship with God. After Jesus is baptized, Mark’s audience is given an insider’s glimpse at Jesus’ connection to God. Here we see what later Christians will call the Trinity: God the Father, the Son Jesus, and the Holy Spirit as a dove, all appearing at once.

The appearance of the Spirit and the voice of God are possible because the heavens have been “ripped open.” The Greek verb here is σχίζω, meaning “ripped or cleaved in two.” The image may refer to a passage in Isaiah 64:1, where the prophet calls to God: “O, that you would open the heavens and come down! [author’s translation]”

Mark narrates Jesus’ baptism in the same way that he portrays John: it is an enactment of Old Testament prophecy. Here, God does rend the heavens and come down to earth in Jesus. If we miss this allusion, the connection between Jesus and God is certainly made clear by the words God speaks: “You are my beloved son, with you I am well-pleased” (1:11). As we have already seen with many statements in Mark 1, this, too, is an allusion to the Old Testament. As God has formerly called the king of Israel “son of God” (e.g., Psalm 2:7), here God calls Jesus not just a son, but a beloved son (see Genesis 22:2, 12, 16). This love and pleasure that God takes in Jesus is the foundation for the rest of the gospel’s story.

Of course, what God’s love of Jesus means is immediately (to use one of Mark’s favorite words) put to the test as the Spirit “kicks Jesus out” (the literal meaning of the Greek verb, ἐκβάλλω) into the wilderness. Yet again, we recognize an Old Testament allusion: Israel, too, was led out into the wilderness at the beginning of its “ministry.” Later generations of Israelites remembered this time in the wilderness as a time of testing (see Psalm 95:7–11), and also a honeymoon period (see Hosea 2:14–23).

Jesus’ own time in the wilderness seems to have both of these interpretations as its background. Jesus is tempted by Satan (Mark 1:13), which clearly coordinates with the Israelites’ own temptation. But when Mark says the wild beasts attend Jesus, it is uncertain whether these beasts are part of the temptation, or a kind of allusion back to the Garden of Eden (compare Isaiah 11:1–11), pointing to a more positive time, or honeymoon, in the desert. Either way, just as Israel’s 40 years in the wilderness served as preparation for their coming to the Promised Land, so Jesus’ 40 days in the wilderness prepares his own way for his ministry.

Good News About God

John’s time of preparation is over by the end of Mark’s introduction: he has already been arrested, and we will not hear the end of his story until Mark 6. The conclusion of John’s ministry of preparation signals the beginning of Jesus’ own ministry. He begins in Galilee, his home (1:9, 14), and he launches his ministry by preaching “good news about God.”

God is now doing something new, as “the time has been fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near” (1:15). This is God’s good news: the time has come for new things! But as God has done before, these new things are described in the language of the old things so that the new is an integral part of the old. Mark’s summary of Jesus’ preaching is almost exactly the same as John’s, and also is the call of the prophets of old: “turn around and put your trust in the good news” (1:15).

Throughout the Gospel of Mark, we can see Jesus saying and doing surprising things. These words and deeds were not only surprising to the scribes, Pharisees, disciples, and various other characters in Mark’s gospel: they may be also surprising and sometimes even dumbfounding to the readers of Mark’s gospel, 2,000 years later. Mark will use old language to describe new things, so that even what is predicted surprises us. Surprises unite the many themes of Mark’s gospel, as Mark describes the coming of God’s kingdom as vivid contrasts, bringing light and darkness, revelation and misunderstanding, life and death. In Mark, surprise is foundational to understanding God’s good news: only when the gospel is surprising can it shape and change our lives into the lives of disciples, who find life by losing it [Author’s Note 3].

Questions for Further Reflection

- How does Mark refer to the Old Testament in the introduction to his gospel (1:1–15)? Note a couple of different ways. What effect do you think this has on the reader?

- Given what the Lectio writer says about Mark 1:9–15, how would you describe God’s relationship with Jesus? Are there times in your life when you understood God’s love and pleasure in you? What about times when you feel that the Spirit has brought you to the wilderness? Looking back, have any of these times been preparation for a season of ministry in your own life?

- In what ways would surprise be necessary to grow as a disciple of Jesus?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Who was “John Mark”? Does the author of Mark’s gospel say anywhere in historical writings how he came upon the information about Jesus that he reports in the book? Was John Mark a companion of Jesus, or of the disciples? Why does modern scholarship date the gospel of Mark to the late first century? (That is, is that the date of the earliest document we have, or do we use other clues?). Do we feel that there are earlier versions, or does the version we have come from oral “tradition”?

Do any of the gospels attempt to directly explain the conflicting aspects of the messiah awaited by the orthodox Jews, and the story of Jesus? (In particular, the Jewish Messiah was to be a descendent of David. The line from David drawn in the New Testament ends with Joseph, who was not Jesus’ father. Also, the Jewish messiah was to save the Jews from their oppressors, primarily at the time, the Romans. The Bible does not say that Jesus attempted to do this).

Question #2.

I was driven to my knees by my own incredibly selfish self will and through that I found that my own sick thinking could not overcome my own sick thinking.

So when the flush of the my spiritual awakening wore off and I found myself in the spiritual valley looking at the many ugly features of my own personality, it took awhile for me to realize this is how God was helping me to change and grow. To heal from my past and to become useful to Him.

I would much rather be on the spiritual mountain top but the fact is that the valley’s and low spots have taught me the most. While I do not welcome them I am grateful for them and how they have brought me closer to Jesus Christ.

Thank you Jesus.

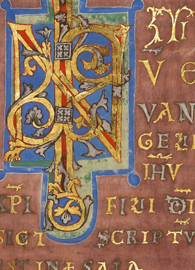

I must thank GOD for this wonderful piece of art, for that is how I see what is of GOD. It allowed me to see the GOD of relationship as I study Gen chpt 1 and chpt 2. I thank GOD for these studies and I read them as I am led by the Holy Spirit, blessing to all involved to a higher education in Christ Jesus, and Jehovah the great I AM in the HOLY SPIRIT.

Aposlte Suprina Ford

I see a chiasmus in Mark 1:1-13. A: Wilderness (make Jesus’ way ‘smooth’), B: Baptism (of the masses – in the Jordon), C (the Center): Promise of future baptism in the Spirit (something to look forward to), B’: Baptism (of Jesus – in the Jordan), A’: Wilderness (Jesus’ way made ‘rough’; e.g., Satan, wild animals). I find it interesting that the chiasmus moves from A/A’ (the wilderness) to B/B’ (confession/purity at the Jordon) to C (the promise of the Spirit). For me this is in line with Israel’s exodus experience: from the wilderness, through the Jordan River, to the promised land (baptism in the Spirit). Overall, I see the entire GoM as a complex chiasmus. Imo, the Gospel could have ended with the fulfillment of the promise in 1:8 (C: a baptism in the Spirit; an empowerment of Jesus’ followers as they moved forward in their own attempts to further the kingdom; serving Jesus.

The treatment of Mark 16:9-20 given by Juel and others leaves something to be desired. Certainly Juel’s claim that “the almost unanimous testimony of the oldest Greek manuscripts” supports the ending at 16:8 is very misleading, inasmuch as only two Greek manuscripts actually end the text there, and over 40 pieces of early (Roman-era) evidence, including patristic citations considerably older than those two MSS, support the inclusion of verses 9-20.

Yours in Christ,

James Snapp, Jr.