Joshua/Judges Week 3

Israel and the “Rahab”-ilitation of Faith: Joshua 2:1–24; 6:22–23

Assistant Professor of New Testament, George Fox University

Read this week’s Scripture: Joshua 2:1–24;6:22–23

13:55

EnlargeIntroduction

EnlargeIntroduction

My covenant. My people. My promise. My land. Thematically, these words echo throughout the whole book of Joshua — Israel’s claiming of the land offered to them by their covenantal God, YHWH [see Author’s Note 1]. The opening chapter of the book focuses on Joshua, who, as we noted last time, is told by YHWH to keep his focus on the divine promise and the presence of God, who has his back.

You might expect, after this, an encounter between Israel and the Canaanites that proves God’s loyalty to Israel in the face of Canaanite adversity. The action, though, is not quite ready to begin. The opening vignette that zooms in on the person Joshua transitions to another personal episode, and one that is of the most unusual and unexpected kind.

The “hero” of this mini-story is not a soldier. He is not an Israelite. He is not even a “he”! Before their faith is tested on the battlefield, the Israelites learn a lesson in the most unlikely place. Hiding in a pile of flax with an uncertain fate resting in the hands of Rahab, a seemingly untrustworthy Canaanite of dubious livelihood [see Author’s Note 2], their concept of God and faith is, as it were, Rahab-ilitated!

Before we can really examine the importance of Rahab in the book of Joshua [see Author’s Note 3], we must set the scene for why two Israelites were in her company in the first place.

Chapter 2 can be broken down into four parts.

- In 2:1, Joshua sends two spies into the land of Canaan with a special interest in the city of Jericho, which was one of the most powerful fortress cities in the land, and they end up in the house of Rahab.

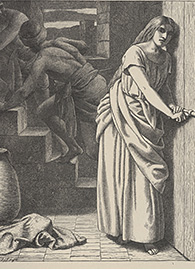

- In 2:2–7, when the king of Jericho gets wind of these intruders, he dispatches his own men to arrest the Israelites, only to have Rahab intercept them and send them on a wild-goose chase.

- While the safety of the spies is secured, they are apparently trapped because the gate to the walled city was closed. Quite shrewdly, it is at that time, in 2:8–14, that Rahab bargains with the spies, offering them an escape plan in exchange for protection for the safety of her family and herself when Israel destroys Jericho.

- The plan is executed, along with the swearing of an oath and the conditions for Rahab’s survival, in 2:15–20.

A Dangerous Liaison?

While the story of Rahab is familiar to many Christians, the question is rarely asked: What are Israelite reconnaissance soldiers doing at the house of a prostitute!? Good question. In the first place, there is no way to get around the fact that she was, in fact, a prostitute.

It may be possible that the spies were there on “unofficial” business, as some interpreters have supposed, but there are two other possibilities as well. First, it is conceivable that a brothel was strategically chosen by the spies because such a place may have been useful (a) as a place that typically safeguarded anonymity and secrecy, and (b) for meeting potential informants who may have valued bribes over national loyalty.

A second possibility is that the “house” of Rahab was not primarily or only a brothel, but a hostel for travelers. A Jewish historian named Josephus from the first century A.D. mentions Rahab as an innkeeper (Antiquities 5:8). Such a viewpoint would certainly make sense of why the spies might visit such a place: there they would be able to listen and talk to locals and travelers away from the public square. Also, this would make sense of the king’s agents’ apparent trust in Rahab’s counsel — if she were more than a prostitute.

However we may evaluate her status in society, though, the shape of the story seems to make clear that she was last kind of person one would expect to be so cunning and perceptive, in both her quick instincts that save her visitors and her extraordinary insight into the power and glory of Israel’s God.

Can We Admire a Liar?

While Rahab certainly shows immediate fidelity towards the Israelite spies, and she is praised for her direct role safeguarding them, she does so through deception: “True,” she says, “the men came to me, but … when it was time to close the gate at dark, the men went out. Where the men went I do not know” (2:4–5a).

If we were watching this scene in a movie, as she is talking, the camera would slowly pan to a pile of flax stalks on the roof and a set of four eyes peeking through! Not only does Rahab play dumb (“I don’t know anything”), she shows initiative in getting the king’s men far, far away from the two spies: “Pursue them quickly, for you can overtake them (2:5b)!”

While this makes for a great story and good action, it has led some readers to a moral dilemma — Is it OK to lie? Do the ends justify the means? How can we reconcile Rahab’s act with scriptural texts that condemn lying, such as we find in Leviticus 19:11?

These are, indeed, difficult questions to answer, but I think it is important to reflect on both the book of Joshua and Scripture in general to address this problem. There are two proposals that are often given in an attempt to make sense of this issue:

- First, you will have some who urge that the whole matter should be downplayed because the focus of the story is Rahab’s faith, not her manner of demonstrating her faith. In reality, though, this is not an answer at all, but a sidelining of the issue. While it may be true that it is not made a matter of great moral tension, I still think we can ask theological and ethical questions in light of this dilemma as Christians seek to learn from and live by Scripture.

- A second answer that is sometimes put forward is that sometimes lying is acceptable. This kind of argument usually focuses on the biblical injunctions against lying and bearing false witness (Exodus 20:16; compare Leviticus 19:11) as sins only because the deceptive behavior is intentionally malicious, damaging, and self-serving. With Rahab, as with the Egyptian midwives who lied to preserve the lives of the Israelite baby boys against the will of Pharaoh (Exodus 1:19), the deception was for the sake of good.

My concern with this particular avenue of approaching the matter of lying is twofold. On the first hand, it can be a very slippery slope, leaving it up to the individual to decide in what context it is all right to lie. Also, perhaps more importantly, it seems to be emphatic in Scripture that God is a God of truth (Romans 3:4; John 17:17). It is his very nature and being to radiate purity and truth. Thus, it would only make sense that this same transparency be the highest ideal.

The most satisfying perspective that can be taken on this issue, I think, is to continue to see lying as not an acceptable practice, as not the way humans were meant to interact. However, because the world is the ugly and chaotic place it is, there may be circumstances where it is the lesser of two evils. In that sense, lying is still evil and “wrong,” because God does not like what is not truth. And yet value can still be found in less-than-ideal acts that are directed at benevolence [see Author’s Note 4].

While it is true, I think, that we can discuss the legitimacy of the problem of Rahab’s deception, I also believe that this episode in Chapter 2 and the attitude towards Rahab in the New Testament treat her as a key model of faith. For example, it would have been hard for a Jewish person reading the first chapter of Matthew to miss the appearance of Rahab in the genealogy of Jesus that traces his path of descendents.

Can I Get A Witness?

Back in Numbers 13, God told the Israelites to send tribal representatives into the land of Canaan to check it out. That early mission in which Joshua himself participated was initiated by God. In the book of Joshua, we do not get a sense that a divine command came to Joshua to scope out the land again.

So why did he send these spies? The LORD had already promised to send his “angel” ahead of him into this land and “blot out” its inhabitants (Exodus 23:23). Many interpreters think that Joshua was wavering, even right from the start, in his trust of the divine plan.

And, if it is true that he had hoped to gain confidence that they could overcome by military strategy, this “recon mission” was a huge blunder: the spies get caught with a prostitute, they are locked inside the city gate, they are preserved only at her mercy, and there is little or no reason to believe they were able to accomplish very much of their clandestine work as they were running for the hills. Some spies! Only with a twinge of irony do they report back to Joshua: “The LORD has surely given the whole land into our hands; all the people are melting in fear because of us” (Joshua 2:24) — at least that is what this Canaanite prostitute keeps going on and on about ….

As the Israelite spies in the story dig themselves deeper and deeper in trouble, Rahab, who has been presented to us as a woman of ill-repute, rises higher and higher in our estimation, especially in her faith in the God of the Israelites. The first time in the narrative that Rahab converses with the spies, she immediately confesses, “I know the LORD has given you this land” (2:9).

In her references to the “Lord” she is technically using the unique divine name that God had disclosed to Israel — “YHWH.” She utters this name several times. Though she names him as “the LORD your God,” as the Israelites’ particular deity, she immediately confesses that he is “God in heaven above and on earth below” (2:11).

Again, the irony is that she shows great faith in the power of this God, but she knows him only from rumors and stories of his might in warring on Israel’s behalf. Compare Rahab’s hope and trust in this God with the Israelites’ continual struggles with loyalty and trust in the Lord — even though they have seen the LORD’s faithfulness up close over and over again.

The book of Hebrews praises Rahab’s faith (11:31), while James praises her works (2:25). The key, though, is that, for all we are meant to know, she was merely a non-Israelite prostitute in a town that was going to be decimated by God’s furious wrath. And yet she could “name and claim” with confidence and at great risk, putting her trust in this foreign god.

And Then There Is Achan

Once you get to Chapter 7, the story zooms in again on a personal figure — the Israelite Achan. He was an Israelite soldier from the tribe of Judah. And yet he tried to keep for himself some “spoils” of the land that were attractive to his eyes, and he stole from the LORD when he grabbed these items and buried them under the ground in his tent. Achan was one who was in covenant with the LORD (“of heaven above and earth below,” as Rahab knew) and yet did what was utterly forbidden and deeply selfish.

When we compare Rahab and Achan, then, the Apostle Paul’s words ring true that God likes to choose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise, and the weak to shame the strong (1 Corinthians 1:27). Whenever the Israelites became proud and self-congratulatory, they needed to be reminded of and humbled by the Canaanite prostitute who had the most sense about her — they repeatedly needed a Rahab-ilitation of their faith, so to speak.

Questions for Further Reflection

- The way this Biblical story is set up, Rahab, at first, is the last person you would think would be a savior (so to speak!) for holy Israelite people. Have you ever encountered someone and made negative judgments about that person right away, but later came to a very different evaluation? What does this kind of encounter as it relates to the Biblical account tell you about yourself and about the ways God? Knowing the Rahab story, how might you handle “first impressions” differently in the future?

- Because this short story about Rahab is so early on in the story of Joshua, it seems to be making an important statement before the “action” really begins. What do you think the reader is meant to learn and know, in advance, before the Israelites lay claim to this land of the Canaanites?

- Do you think Rahab’s act of lying to save the Israelite guests was sinful, noble, “just acceptable,” or something else? Is it an example for Christians to follow? How does her story relate to the example of Dietrich Bonhoeffer who, in an attempt to destroy Hitler’s power from the inside, became a double agent, which involved living an ongoing lie.

- Rahab is one of only a few women specifically mentioned in the genealogy of Jesus (Matthew 1:5). What is significant about her place in the lineage of the Messiah (Hint: Think about her gender, nationality, etc.)? What does this tell us about God’s saving work?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Joshua/Judges Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Thank you for your dedication with sharing about Christ to others. Your outline about Rahab, helps me with my Faith and to not judge others. There’s a lot to think about with these passages.

Emily, so glad to hear that Rahab’s story has been challenging! I, too, love her story– especially that she was a key player in the lineage of Jesus. God is so faithful to work in and through us no matter our life history. Blessings to you as you continue to study God’s Word!