James Week 6

James as the Introduction to the Catholic Epistle Collection

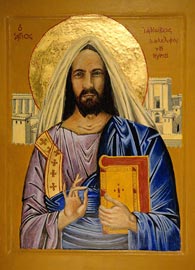

Enlarge

Enlarge

We have completed our tour of the Letter of James. But our work isn’t finished yet! Indeed, this letter did not come down to us in isolation, but was delivered as part of a larger package — a whole Scripture — within which James was intentionally placed in order to perform a particular role. In order to really receive James as Scripture, we must attend to the role it plays in the Bible.

In our first week, I spoke of the diversity of our holy Scripture. The Bible is a single book, yes, but this book is in fact a collection of various “book collections” — prophets, gospels, letters, etc. — designed to function together to provide us with a whole word from God. Viewed from this perspective, we see that the letter of James has been passed down to us as the lead letter in a collection called “the Catholic Epistles” (the letters of James, Peter, John, and Jude).

As I’ve already described, historical evidence strongly suggests that one of the reasons this collection was created was as a response to people we called “Paulinists.” These folks championed the Pauline writings in a manner that got them into trouble. Some ended up opposing Christianity and Judaism. Others opposed the present activity of the Spirit with the revelation of God made known in Christ Jesus. Many others opposed associating faith with obedience.

As it turns out, our earliest accounting for why these books were added to the Bible insists that they were included to ensure that believers didn’t misread Paul and end up disconnecting faith and deeds. According to Augustine of Hippo (writing ca. 413),

Even in the days of the Apostles certain somewhat obscure statements … of the Apostle Paul were misunderstood, and some thought that he was saying this: “Let us now do evil that good may come from it” [Romans 3:8] because he said “Now the law intervened that the offense might abound. But where the offense has abounded, grace has abounded yet more” [Romans 5:20] …. Since this problem is by no means new and had already arisen at the time of the Apostles, other apostolic letters of Peter, John, James and Jude are deliberately aimed against the argument I have been refuting and firmly uphold the doctrine that faith does not avail without good works. [Author’s Note 1]

Augustine’s essay goes on to offer a wide-ranging reading of the apostolic letters in order to arrive at a wholly apostolic understanding of the relation between faith and works. Augustine’s primary Pauline text in the essay (repeated 10 times) is Galatians 5:6, which insists that “the only thing that counts is faith working through love.” This is interwoven with almost 30 references to the various Catholic Epistles and many more from the gospels.

If Augustine is right (and I think he is), it means that some of us might need to change our understanding of how the Bible is meant to function. Though we might be troubled by apparent “contradictions” in the Bible, we needn’t be; instead, we might employ other ways of accounting for how texts relate to one another. Texts may be in tension, or in conversation; they may be meant to stand in a complementary relationship with other texts, or to offer correctives to potential misunderstandings of other texts. All this is to say that the Word of God is not found in single verses quoted out of context. The Word is heard by means of Spirit-inspired, wise syntheses of the diverse words found in our Scripture.

I believe the letters of the Catholic Epistles collection are meant to be read together in order to offer up a unified theological witness. [Author’s Note 2] Let me close this Lectio series on James, then, by offering up a handful of ways in which the letter sets the tone for the Catholic Epistle collection as a whole. You might begin by reading all seven letters in sequence (the whole collection is smaller than 2 Corinthians). I have three points to make.

- Believers reside in a “diaspora” in which they experience trials of faith. James began things by addressing his readers as “the twelve tribes in the diaspora,” saying, “whenever you face trials of any kind, consider it nothing but joy, because you know that the testing of your faith produces endurance” (James 1:2). Here the particular trial is the seduction believers experience living in the world, particularly the desire for material goods, which, in turn, results in community-destroying envy.As we go on through the other six Catholic Epistles, we discover that each of them describes a particular “trial” believers experience in the world. 1 Peter begins by mirroring James, addressing his letter in similar fashion “to the elect exiles of the dispersion” (1 Peter 1:1), and goes on to use almost the same language in calling believers to “rejoice, even if now for a little while you have had to suffer various trials, so that the genuineness of your faith … may be found to result in praise and glory and honor when Jesus Christ is revealed” (1:6–7). In 1 Peter, however, the trial is not worldly seduction but the endurance of abuse coming from nonbelievers who do not understand why Christians live differently than they do. 1 Peter refers to believers as “aliens and exiles” in the world, a people who must maintain distinctive practices in the world — for their merciful, patient, and pure behavior is designed to direct unbelievers toward faith in the living God.In 2 Peter and Jude, the trial described is not abuse coming from ungodly pagans, but seductions away from right faith and deed being promoted by ungodly Christians. Sometimes these Christians promote false doctrines, as in 2 Peter, where readers are warned against those who deny that Jesus is coming again to judge the living and the dead (see, e.g., 2 Peter 1:16–20 and 3:1–13). Other times, Christians promote ungodly behavior, like those described in Jude, who “pervert the grace of God into licentiousness and deny our only Master and Lord, Jesus Christ” (Jude 4). Sometimes those Christians break off into a splinter group, and Christians must deal with the trial of schism. Such is the case in 1–3 John, where believers are warned, “do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God; for many false prophets have gone out into the world” (1 John 4:1). All this is to say, the Catholic Epistles insist that believers must expect to experience trials of faith. Such periods of pain are not meaningless miseries but occasions designed to purify their faith in God. [Author’s Note 3]

- Happily, God has not left us alone in our suffering, but has disclosed a “word of truth” for us and for our salvation. James set the tone by calling believers to open their ears, shut their mouths, and “receive with meekness the implanted word, which is able to save your souls” (James 1:19–21, ESV). Not only has God “brought us forth by the word of truth” (1:18); God has revealed “wisdom from above” (3:17), which will guide our feet into the way of peace. We must resist anger and envy, and humble ourselves before the Lord and before one another.1 Peter in turn speaks of “the living and abiding word of God” through which we are “born anew” (1 Peter 1:23–25). Here the word of truth is the good news of the resurrection (1:3–5) preached by the apostles of Jesus (1:25). This word reframes the way we conceive of our existence; because Jesus passed through suffering and death into a resurrection to new life, so we too can let go of the temporary and perishable aspects of this life “in order to take hold of the life that really is life” (1 Timothy 6:19).2 Peter and Jude encourage us to turn to the “prophetic word” of the Old Testament “as a lamp shining in a dark place” (2 Peter 1:19), as it is an especially reliable source of Christian wisdom to negotiate the trials of life. Among other things, this word provides valuable stories of characters who function as “types” by which we might recognize examples of godliness and ungodliness in our midst today. Noah, Lot, and Michael the Archangel (2 Peter 2:5, 7; Jude 9) provide examples of righteousness and humility, while the fallen angels of Genesis 6, the people of Sodom and Gomorrah, and the faithless generation of Israelites in the desert (2 Peter 2:4–6; Jude 5–7) provide different examples of ungodliness.In similar fashion the letters of John speak of a “word of life” that was heard, seen, looked upon, and touched by the first Apostles of Jesus; these in turn proclaimed it to us, so that we all might have fellowship with God and with one another (1 John 1:1–3). That “word” is not a static thing, but a living and active word of God (Hebrews 4:12) that somehow “abides” in us, and we in it (1 John 1:10; 2:4–6). Believers “keep” this word by walking in it (1 John 2:5–6; 2 John 4–6), most especially by following the model of Jesus, who taught us how to love as God loves.

- Finally, in response to this word, God’s people must practice pure and undefiled behavior. James was clear that simply believing and saying the right things do not indicate true friendship with God. No, the truth that resides in our minds and on our lips must be embodied in works of love; else we deceive ourselves into thinking that we actually are Christians simply because we engage in faith-talk. James insists that faith doesn’t work when it isn’t accompanied by works!1 Peter agrees wholeheartedly. People who are born anew by God (1 Peter 1:3, 23) must be obedient to Jesus (1:1), put worldly behavior behind them (4:1–5), and instead take up their identity as aliens and exiles in this world (2:11–12). Like James, 2 Peter insists that “faith alone” is not enough; it must be supplemented with the virtues of Christian life (2 Peter 1:3–7). Those who do so will not only be kept from being “ineffective and unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1:8), but also “confirm their call and election” and, in so doing, find that “entry into the eternal kingdom of our Lord will be richly provided” for them (1:10–11).In their own way the letters of John make the same point that faith and works must be joined. “If we say that we have fellowship with him while we are walking in darkness, we lie and do not do what is true; but if we walk in the light as he himself is in the light, we have fellowship with one another, and the blood of Jesus his Son cleanses us from all sin” (1 John 1:6–7).

“We know love by this: he laid down his life for us, and we ought to lay down our lives for one another. How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses help? Little children, let us love not in word or speech but in deed and action (1 John 3:16–18).

Indeed, “those who say, ‘I love God,’ and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen” (1 John 4:20).

The Catholic Epistle collection ends with a little letter from Jesus’ little brother Jude. This “servant of Jesus Christ” begins his letter reiterating what I take to be the central theme of the collection as a whole: Some believers are twisting the grace of God into a license to act immorally. They want to claim Jesus as “Savior” without also making him “Lord” and “Master” of their lives (Jude 4). Jude has hard words for us. Remember, he says: long ago God saved people out of Egypt only to condemn them later in the desert because they rebelled (Jude 5). Remember the horrible judgment suffered by the peoples of Sodom and Gomorrah, whose unchecked lust led them to abuse vulnerable strangers (Jude 7). Remember that the Savior you adore is coming in power to judge us all for our ungodliness (Jude 14–15).

How ought we to live as a result of this knowledge? Jude ends with five quick bits of advice we’d be wise to heed (Jude 20–23). [Author’s Note 4] “Build yourselves up on your most holy faith” — that is, work to grow in Christian knowledge and virtue. Strive to “pray in the Holy Spirit,” not in the worldly spirit of desire, anger, or envy. Rather than assume a passive posture in the face of God’s forgiveness, work to “keep yourselves in the love of God,” for doing so will enable us to live in hopeful expectation of “the mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ” on judgment day.

Finally, since we’ve already been told that “mercy triumphs over judgment” (James 2:13), the best way to prepare for God’s coming judgment is to offer mercy to everyone — regardless of whether they are doubting Christians, disputing non-Christians, or those depraved by habitual sin (Jude 22–23). “We love,” says 1 John, “because he first loved us.” The Catholic Epistles as a whole insist on this crucial piece of “wisdom from above”: We who have experienced God’s love must respond by humbly turning our whole lives — our heads, hearts, and especially our hands — into instruments of God’s love and peace for the healing of the world.

| Catholic Epistle “Pillars” Collection | Pauline Collection | |

|---|---|---|

| Mission Focus According to Acts 1:8 | Mission to Jews; centralized witness “in Jerusalem and Judea” | Mission to Gentiles: traveling witness “to the ends of the earth” |

| Understood According to Romans 1:16 | Salvation is “to the Jew first …” | “… and also to the Greek.” |

| Nature of Apostolicity | Eyewitnesses of Jesus’ words and deeds | Revelatory call from the Risen Christ |

| Letter Genre | Encyclicals written from “home”(titled “the letter of___”) | Missionary words “on target”(titled “to the ___”) |

| Posture | More sectarian: “Do not love the world” | More evangelistic: “I become all things to all people” |

| Emphasis | Orthopraxy: living according to what God has done in Christ | Orthodoxy: rightly understanding what God has done in Christ |

| Narrative of Salvation | Sanctification: our right response to God’s graceful initiative in Christ | Justification: God’s saving initiative in Christ |

| Authorial Voice | Pastoral: restoring believers to faith | Missionary: bringing outsiders to faith |

Questions for Further Reflection

- As we wrap up our study of James, Dr. Nienhuis reminds us of the function of the Catholic Epistles in the overall narrative of the Bible. What is this role, and what do we learn about reading Scripture because of this? (Hint: Check out the paragraph that begins “If Augustine is right …” to jog your memory) Is this a new way of thinking for you? Why or why not?

- This week’s Lectio highlights three themes that begin in James and carry on throughout the rest of the Catholic Epistles. Which of these themes is most challenging to you, and why?

- This summer the Lectio has looked at the theme of wisdom through both the Old Testament and the New Testament. What is one thing you have learned about wisdom through these studies?

- If you were to describe the book of James to someone who had never read it, where would you start? What would you list as its most important points and/or its role in the life of Christian discipleship? What aspects of the book will you continue to wrestle with even as we finish our study?

<<Previous Lectio Back to James Next Lectio Series (Revelation) >>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Dr. Nienhuis – Thank you so much for such an informative study of James. I finished a study of James earlier this year and your study provided more insight into areas not touched on in my earlier study. One of God’s greatest gifts is that His Word is alive and active and I appreciate so much reading a book or a verse at different times of my life and God speaks to my heart and gives me more wisdom and insight into His character.

Blessings,

Judy Cleveland

Class of ’74

Thank you for the reminder that the scriptures tell us to have Jesus as our Savior AND Lord and Master of our lives.